Francesco Spampinato ’06GSAS is a historian of contemporary art and an enthusiast of vinyl records. His 2017 book Art Record Covers explores the connections between fine art and mass media through a survey of over five hundred album covers.

How does this book relate to your studies?

I’m interested in understanding what happens when art and pop culture converge. My book, which is the first to focus specifically on covers by modern and contemporary artists, examines the evolution of the record cover format in relation to artistic movements and styles.

Talk about the relationship between pop culture and art.

In the 1960s, the pop-art movement collapsed hierarchies between highbrow and lowbrow — between paintings and comic books, for example — and, in many ways, art and pop culture have been connected ever since. Musicians were inspired by visual artists to develop a new form of, let’s say, avant-garde for the masses. Pop music was no longer just entertainment; it became a way to convey political messages and to reshape society. And musicians started to collaborate with pop artists, like Andy Warhol, Peter Blake, and Jann Haworth.

Most people stream and download their music. Why are physical records still relevant?

I think we somehow need to have a tangible experience with music. The mid-2010s saw a huge revival of vinyl records; US sales have grown every year for twelve years straight. For me, this comeback is about more than just nostalgia. The Internet has caused us to lose some of our previous ways of interacting with reality, and a record is a touchable and relatable thing.

What makes a great album cover?

It should make you stop and think critically about what you’re looking at. A great cover by an artist isn’t a mere transposition of his or her work but an image that adapts to the rules of media and marketing, and that also echoes the music. It maintains the intellectual dimension of the artist’s oeuvre but in a different context.

5 Important Album Covers Worth a Second Look

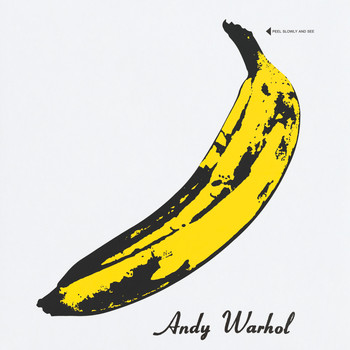

The Velvet Underground & Nico (self-titled), 1967

Cover art by Andy Warhol

This is one of the most iconic covers of all time. Warhol’s artwork suggests that even bananas can be repurposed as mass media — the image on the cover is a sticker that, once removed, reveals a peeled banana underneath. As the band’s manager, Warhol also proposed a new role for the artist as a producer of mainstream culture.

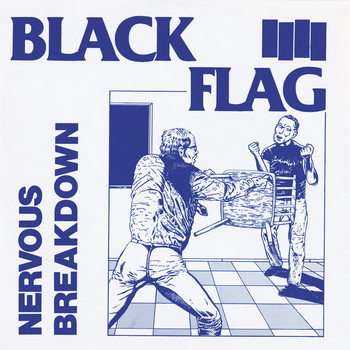

Nervous Breakdown (Black Flag), 1980

Cover art by Raymond Pettibon

Pettibon is an artist who really understands the relationship between art and music. His cover for Black Flag’s first EP reflects the energy of punk and the compelling need of young people to rebel against the society of adults.

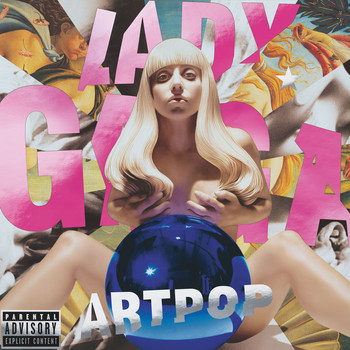

Artpop (Lady Gaga), 2013

Cover art by Jeff Koons

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Koons did a series of erotic photos and sculptures of himself with his then wife, the porn star Cicciolina. Gaga approached him to create something similar. She even references Koons in her song ‘Applause’ with the lyric, ‘One second I’m a Koons, then suddenly the Koons is me.’

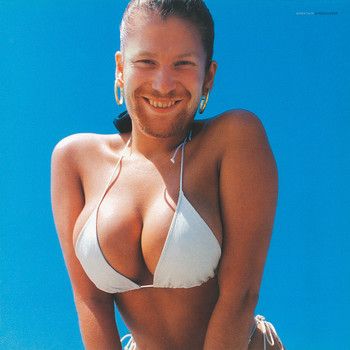

Windowlicker (Aphex Twin), 1999

Cover art by Chris Cunningham

The cover of this single is derived from Cunningham’s music videos for Aphex Twin. I remember the joy of watching his work on MTV and then seeing it at major art shows. It was proof for me that art can originate in pop culture and then be appreciated and acknowledged by the art world.

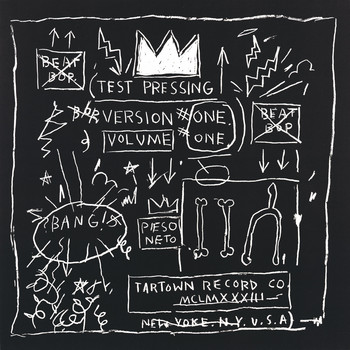

Beat Bop (Rammellzee vs. K-Rob), 1983

Cover art by Jean-Michel Basquiat

This is a fundamental record. First, because this ten-minute rap battle is a hip-hop milestone. Second, because Basquiat made the cover in his neo-expressionist style borrowed from infographics and cartoons. Third, because graffiti artist Rammellzee raps on it. Last but not least, because Basquiat produced it himself.