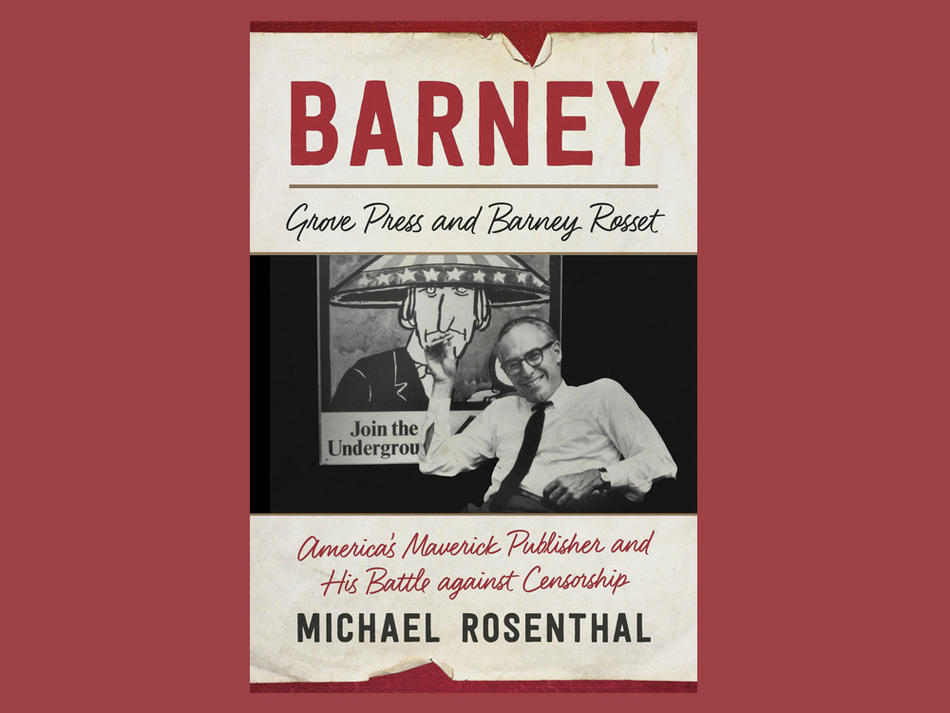

Michael Rosenthal’s entertaining biography of Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset claims that Rosset “was unquestionably the most daring and arguably the most significant American book publisher of the twentieth century.” While Charles Scribner, Roger Straus and John Farrar, Bennett Cerf ’20CC, and others might joust over “most significant,” Rosenthal ’67GSAS, in just under two hundred pages, certainly makes a convincing and enjoyable case for Rosset as the most daring.

A touch of hyperbole is almost obligatory in sketching Rosset’s “ferocious competitiveness” and “instinctive genius” for risk-taking, both in the books he decided to publish and in the lawsuits he took on to defend them. Rosenthal notes that in the landmark fight over Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, Rosset from his own pocket “funded sixty [trials] in twenty-one states” at a cost of about two million dollars in today’s currency, a herculean effort that ended finally in a Supreme Court victory in 1964. “No one but Barney could have prevailed,” Rosenthal contends. Thanks to Rosset, by the end of the 1960s, American literature had been forever freed from obscenity laws.

In the compelling tale of the three major First Amendment cases that form the book’s central triptych of Rossetian accomplishment — Tropic of Cancer, D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch — Rosenthal’s clear admiration for Rosset is tempered by seeing his impetuous subject whole. Calling him only “Barney” throughout, Rosenthal achieves both an amused familiarity and an ironic distance that help underline his characterization of Rosset as “eternally young — some might say adolescent,” a “radical anomaly” in a conservative business, forever happily suffused with undergraduate enthusiasm. (Rosenthal notes that Rosset first read Tropic of Cancer after he bought a contraband copy under the counter at a New York bookshop during his first — and only — year at Swarthmore.)

Rosenthal, who is the former Campbell Professor in the Humanities at Columbia, where he taught for thirty-seven years, has made illuminating use of the Rosset papers in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The narrative goes cradle to grave to suggest the origins and trace the effects of the publisher’s unassimilated teenage sensibility, which led to rebellions of every sort, including publishing Victorian spanking literature alongside Nobel laureates. In his own time, Rosset’s popular reputation as a cheerful pornographer sometimes threatened to overshadow his visionary taste: Rosset was the first to bring both the unexpurgated Marquis de Sade and the film I Am Curious (Yellow) to the US, even as he was publishing The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. It was Rosset who introduced American readers to Samuel Beckett, Pablo Neruda, Harold Pinter, Marguerite Duras, Octavio Paz, Jean Genet, Tom Stoppard, Kenzaburo Oe, and Mario Vargas Llosa.

Rosenthal does not shy away from Rosset the abusive boss, Rosset the sexual adventurer (in and outside of his five marriages), Rosset the inept businessman, Rosset the domineering (“even vicious”) husband — all the Rossets fueled by an apparently continuous intake of booze. In fact, Rosenthal is often at his wry best when framing some of the more notable excesses of his subject and the era. Describing Burroughs’s shooting of his wife in an apparent “William Tell” demonstration at a Mexico City bar, Rosenthal writes, “Unfortunately, alcohol had rendered his hand less firm than he thought and the demonstration ended only by showing that a bullet in the head is likely to prove fatal. Mexican authorities treated it as an accident.”

Rosenthal is fascinating on Rosset’s role in bringing Waiting for Godot to an American audience, though readers may be forgiven for wishing for comparably juicy detail about some of Rosset’s other notable acquisitions. But brevity, the soul of this book’s wit, is an essential part of its charm; Rosenthal’s previous studies of complex cultural figures — Lord Robert Baden-Powell (founder of the Boy Scouts) and Nicholas Murray Butler (Columbia’s president for nearly the entire first half of the twentieth century) — were longer and more academic.

“In taking forbidden, offensive, and little-known work and finding an audience for it,” Rosenthal writes, Barney Rosset “bestowed gifts on writers and readers everywhere.” Michael Rosenthal, in taking a little-known and once-offensive publisher and turning insightful and witty attention on him, has bestowed his own gift on readers everywhere.