If I were asked to name the single work of American literature that is most widely read and discussed in cities and towns, colleges and universities across India, my guess would be John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The choice is natural — conversations in India about rural–urban migration and the struggles of village folk who turn into badly paid and barely protected industrial workers have often reminded me of Steinbeck’s Joad family. And while the worker is a key figure in American literature, particularly over the last century, he is curiously absent from contemporary Indian fiction.

That gap is gradually being filled by a growing number of nonfiction writers. The first wave of “New India” books, published in the last decade, sought to describe and explain the country of a billion people and capture the changes to that country brought on in part by India’s rising economy. As Indian entrepreneurs oversold the story of the nation’s imminent superpower status, correctives to that vision began to emerge as well: the Pulitzer Prize –winning American journalist Katherine Boo ’88BC published her extraordinary account of life in a Bombay slum, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, and the New York–based Indian writer Siddhartha Deb ’06GSAS traveled across the country to report his account of India’s gilded age of new money and new poverty in The Beautiful and the Damned.

Aman Sethi’s A Free Man is an excellent addition to these books, which bring into sight the hidden worlds of India’s have-nots. Owing to the high growth rate of the Indian economy over the past decade, the number of Indians working as laborers in construction has more than doubled, from 18 million in 2000 to around 44 million in 2010. Sethi ’09JRN, a young reporter who grew up in New Delhi and worked there for a magazine, sets out to understand the life of just one of those 44 million.

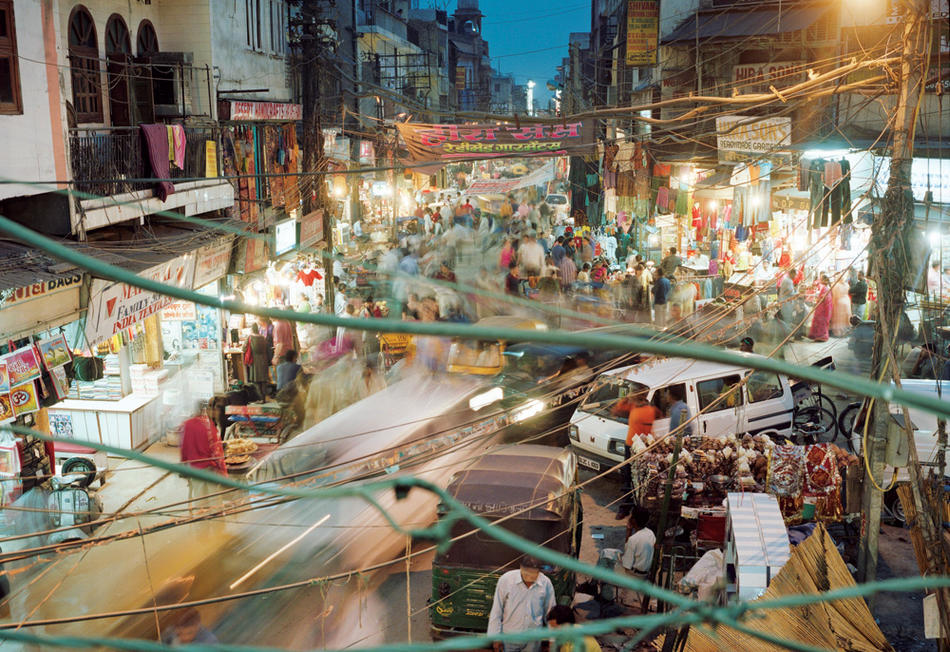

Sethi met Mohammad Ashraf, a forty-year-old house painter, and his friends in a decrepit, crowded part of Delhi abutting the city’s Muslim ghetto. Bara Tooti is a labor market populated by painters and plumbers, salesmen and repairmen, rickshaw pullers and cigarette sellers, mazdoors (laborers) and mistrys (masons), a place “on the streets of which daily wagers like Ashraf live, work, drink, and dream.” It provides work and wages a man can survive on, but it is a hard, exacting place, where the pressures of life often send people into hospitals, drive them mad, or even kill them at an early age.

Ashraf and his friends live on the street. They have stitched pockets in the insides of their shirts and pouches into the waistbands of their trousers — on-person vaults where they keep their money, identity papers, and phone numbers of homes they left years ago. In the mornings, except when they are too hung-over, they squat with their tools in the Bara Tooti and wait for contractors to pick them up for a day’s work: painting a wall, repairing a roof, or lugging bags of cement and piles of bricks up construction- site scaffolding.

Ashraf wasn’t always homeless. In fact, his beginnings were promising: his mother was a maid in the house of a professor in the North Indian state of Bihar; the professor sent Ashraf to school and eventually to college, where he studied biology. But then the lonely professor’s house became the focus of the land mafia — increasingly pervasive groups of political officials who acquire, develop, and sell land illegally. Thugs began to surround the professor’s house. To ward them off, Ashraf fired at the mafia boss with the professor’s handgun, but missed. The mafia left, but weeks later the professor was killed in a mysterious car accident, ending Ashraf’s hopes of a better life. Fear pushed Ashraf out of Bihar, onto a long journey as an itinerant laborer: he worked as a farmhand in Punjab, a butcher in Bombay, a marble-tile polisher in Calcutta, and a tailor in Delhi before ending up on the streets of Bara Tooti.

Sethi spent more than five years meeting with Ashraf to tease out the texture and timeline of Ashraf’s current life and the many lives he led before coming to Bara Tooti, which makes for a rich, detailed portrait. Sethi’s diligence also reveals the market dwellers’ inner selves, their loneliness, their compassion, their friendships, and, in a recurring theme, their dreams of striking it rich. “Everyone at Bara Tooti has at least one good idea that they are convinced will make them unimaginably wealthy,” Sethi writes.

The person in Bara Tooti who comes the closest to succeeding is Kalyani, an entrepreneurial woman who runs an illegal bar and falls into a lucrative second enterprise. Adjacent to Bara Tooti is a bazaar where grain merchants unload trucks of expensive basmati rice into warehouses. The laborers use iron hooks to load and unload the jute sacks from the trucks, spilling some grains of rice in the process. Kalyani moves in like a sparrow, sweeping up “the mixture of grain, mud, and grit into a gunny sack” and sifting it to get several kilos of “fragrant basmati rice.” A few months into her venture, Kalyani collects between ten and fifteen kilos of rice every day. She strikes an arrangement with the warehouse owners and hires an army of workers to collect and clean the spilled rice.

Neither Ashraf nor his friends Rehaan and Laloo are that fortunate. After cycles of working and drinking, their loneliness and luck do them in. Rehaan, who fantasizes about making money by opening a goat or pig farm in his North Indian village, falls from a ladder on a construction site. “Dropped off a tall ladder, these bones shatter, these muscles tear, these tendons snap, and when they do, they leave behind a crumpled shell in the place of a boy as beautiful and agile as Rehaan,” Sethi writes in one of the most moving passages of the book. Laloo, already plagued with a limp, goes mad and is seen running naked after cycle rickshaws, with fists full of rupees, shouting, “Two hundred rupees for the day. Today I want to see all of Delhi, everything.”

And Ashraf himself, with Sethi’s financial support, moves to Calcutta, looking for an old friend and the life he left behind. But there, too, he ends up on the street, and eventually in a hospital with tuberculosis. Sethi goes beyond the conventional duties of a reporter, helping Ashraf with money and sending his friends over to help, but the two men’s phone calls to each other, which animate the book with great dialogue, eventually stop. Ashraf disappears from the hospital, leaving Sethi only to hope that someday Ashraf will call him at midnight, as was his way, and say, “Aman Bhai, I hope I didn’t disturb you. You should come see me some time.”