Her cell phone rang for the tenth time in an hour, and for the tenth time, she let it go to voice mail. When she opened her purse on the sidewalk, it was only to get her keys. She entered the lobby of her building, but before she reached the elevator, the phone rang again. Reception died inside the rising car and she breathed audibly with relief.

The doors opened, and she walked the hallway to her apartment. Twenty feet from her door, the phone buzzed again. She juggled her purse and her dinner and unzipped the purse, ready to throw the phone at the wall. But then she saw the number: a 305 area code. She pressed the button quick.

“Mom? Are you OK?”

“Samantha Cooley, I have been ringing this phone since morning!”It wasn’t her mother. It was a man. Samantha stiffened.

“Samantha?”

It was her father. His calls were as rare as a solar eclipse. She set down her bags, hung her head.

“I’m sorry, Dad. I thought you were someone else.”

Her father cleared his throat twice. A tic that meant trouble.

“Someone came to our window,” he said, quietly. “And smashed it.”

Samantha touched the wall for balance. “What are you talking about?”

Her father raised his voice slightly and enunciated each word. “A man walked into the yard of our home and smashed our kitchen window with a brick.”

“Oh, my God!” Samantha said. “Are you all right? Is Mom?”

“Your mother and I were in the living room. We weren’t hurt.”

Samantha realized where she was now: standing in the hallway of a building she’d been living in for only three months. She felt exposed. She picked up her purse and two plastic bags and walked.

“OK. OK,” she said, reaching her door. “No one’s hurt. That’s good.”

She rifled through her purse for her keys again, tilting her head and raising her right shoulder to keep the phone pressed to her ear.

Her father said, “Before this man ran away he shouted something. I didn’t hear him too well, but your mother did.

”Samantha found the keys, turned the top lock. The click echoed in the long hall.

“He said, ‘Tell your daughter this is about what she owes us!’”

Samantha almost dropped the phone. “Are you serious, Dad? Is this a joke?”

“You think I’d joke about someone attacking your mother and me?”

Samantha stepped inside, dropped her purse, and nearly tripped over it. She stumbled forward in the dark while the door slammed shut behind her.

“Didn’t Mom want to replace the kitchen windows anyway?” she half joked. Her father didn’t laugh.

“Your mother told me not to call you. She didn’t even want to be in the house when I did. You better not be in touch for a while.” He hung up.

Samantha stepped into the kitchen, holding the bags, the phone still squeezed to her ear, even though her father wasn’t there. She flicked the light switch beside the oven.

She could have screamed, but didn’t. There, sitting cross-legged on the kitchen floor, his back against the fridge, was a man she didn’t know.

“You’re back,” he said, almost pleasantly.

Samantha’s reaction surprised even herself. She lifted the plastic bag in her right hand and said, “All I have is Chinese food.”

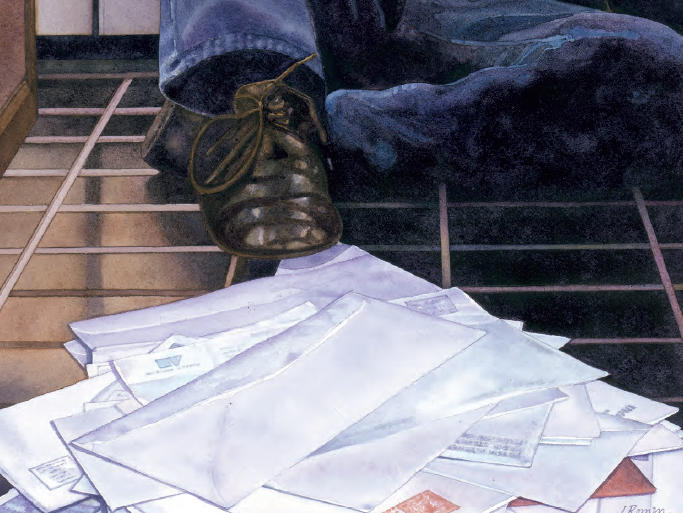

The man pushed himself up, brushed at the wrinkles of his cheap sport coat. Samantha noticed, on the floor in front of him, a large pile of her old mail. Maybe he’d been looking for uncashed checks. Arranged on the small breakfast table were her DVD player, an iPod, a coffeemaker, and an electric toothbrush.

“I’m going to need more than Chinese food,” said the man.

Samantha felt fear in her toes, running up through her legs. She couldn’t move. The front door wasn’t so far off, but she couldn’t even make herself lower the bag of food.

“You’re not . . . ” she began, but didn’t know how to finish the sentence.

You’re not supposed to be here. You’re not staying. You’re not going to hurt me.

The man stood very tall. He had a long, narrow nose that pointed downward, almost over his lip. He looked like a stork, actually. Samantha tried to memorize his face, but her eyes wouldn’t focus.

“My name is Paul Horvath,” he said. “You didn’t answer any of these.” He kicked at the stack of mail. “But at least I see you got them.”

Samantha stared at the pile. Horvath. Where did she know that name?

“If you’d ever picked up your phone I wouldn’t be here now,” Horvath said. “And my associate wouldn’t have thrown a rock through your parents’ window.”

Now Samantha remembered him.

Hello, Ms. Cooley, my name is Paul Horvath. This concerns an urgent business matter. Would you please return my phone call at . . .

How many times had she heard that voice, that phrase, and just deleted the message? Dozens? Sometimes there were nine or ten in a single day.

Samantha felt her stomach drop, like when she was a kid and her mother had caught her swiping money from her dad’s wallet. Her face was hot. She blinked rapidly. The last thing she wanted to do was cry.

To compose herself, she went to the cabinet over the stove and took out two plates. She set them out on the counter and took out the Chinese food. Brown rice, steamed vegetables, an order of dumplings.

“At least,” said Horvath, eyeing the spread, “you’re not spending your money on gourmet food.” He looked at her, then quickly shook his head, as if ridding himself of a moment’s sympathy.

Samantha opened the white cartons. She said, “Do you want a fork or can you handle chopsticks?”

Horvath frowned, as if disappointed he hadn’t scared her. “Fork, I guess.”

That helped Samantha relax a little. At one school in Suffolk County, where she’d been a substitute teacher for two months, a 13-year-old boy had pressed a gun to her thigh when she passed his desk. He just wanted to see her cry. And she had cried, but the experience had toughened her. Two college degrees, and that’s the most she’d earned out in the real world — a little bit of backbone.

Samantha opened the drawer for the silverware. The knives shone in the light. She pulled out a fork and slid the drawer shut fast.

Horvath picked up his plate, but just stared down at the white cartons of food.

Samantha served herself. She wanted desperately to run, climb out a window, anything, but instead she took her plate and sat at the breakfast table. Using her chopsticks, she brought a clump of rice to her mouth and chewed slowly.

Horvath finally took a couple of dumplings and sat down across from her.

The DVD player and the iPod and the coffeemaker and the electric toothbrush were in his way.

“What’s that all about?” she said, pointing with her chopsticks.

Horvath’s long nose twitched. “Collateral.”

“The DVD player’s mine,” she said. “But not the rest.”

Horvath looked confused. “You have a roommate?”

“I’m subletting. The place came furnished.”

Horvath deflated in his chair.

“I pretty much live by sublet,” Samantha told him. This was true. She’d moved 11 times in the past 6 years. “I keep a storage locker up on . . . ”

She caught herself. “I keep a storage locker for clothes. When the summer’s over, I go in and get all my winter stuff. When winter’s over, I go back and make the switch.”

She flicked at the shoulder of her white short-sleeve blouse. Four years old and fraying at the collar, but a luxury when she’d bought it. Running to teaching assignments all over town had kept her thin, which allowed her to keep wearing the same clothes. That, plus she often skipped meals.

Horvath shook his head. “I don’t make much, either, but I live a lot better than this.”

Samantha bit into a piece of broccoli. “I used to think suffering was part of the point of coming out here.”

Low pay, even less respect. The worst junior high schools in the city. She’d actually felt all that was romantic once.

“You could’ve paid off something.” Horvath popped a dumpling into his mouth.

“On my salary?”

“You could’ve picked up the phone.”

Samantha considered this. Despite her wish to defy Horvath, she couldn’t really disagree with him. She had, after all, run out on her debts. Now those debts had grown. Thirty thousand in student loans had, by now, ballooned to nearly $70,000.

She’d never felt she had enough to afford a payment, not even the minimum of $100 a month. Not even $50. Saving seemed impossible. She’d always assumed she’d get a full-time teaching job some day, a regular income from which she could start to repay. She still believed it would happen. She just hadn’t managed it yet.

To avoid the whole business, she would move into new sublets before the billing statements could catch up. And she stopped offering forwarding addresses. Maybe the debt would simply disappear if she ignored it long enough.

Sometimes she even bought lottery tickets, thinking she’d hit it rich and pay off the loan in one lump. She kept hoping something would happen, that things would break her way. She knew this wasn’t logical, but still, she hoped for it.

“So what do you want?” she said.

“Five years I’ve been after you, Ms. Cooley. And you treated me like a . . . like a stink bug. I have no doubt that if I let you go, you’re just going to disappear again.”

Samantha didn’t want any more food. She didn’t even want to look at it.

“It’s getting late, Samantha. I suggest we come to some sort of agreement.”

Samantha looked into Horvath’s strangely youthful face.

“What kind of agreement?” she said.

Horvath stood up. On reflex, Samantha slid back in her chair. “I was in here a while before you got back,” said Horvath. “I looked through every closet, every drawer.”

“I told you, none of this is mine to give,” Samantha said. “I understand,” said Horvath. “But I have an idea.”

Samantha watched as Horvath went to the countertop near the oven. He pulled out the drawer containing the silverware.

He said, “I’m really not asking for much,” and reached into the drawer.

At the hospital, Samantha stuck with her story about hurting herself while cooking dinner. This, despite the nurses and the doctor all commenting on how perfectly clean the wound appeared to be. It was bad enough that the doctor actually called the police. She said she had to because she suspected Samantha might have been a victim of domestic abuse. But Samantha told the cops no more than she’d told the hospital staff. Her wound was dressed, she was given a prescription for pain medication, and then the cops drove her back to her apartment. They walked her inside and checked every room, but Horvath was long gone.

The cops noticed the blood streaked across her kitchen counter, and the meat cleaver in the sink. The cops, two good guys, then spent about 15 minutes trying to help her find the top half of her right pinky. She played along with it. When they discovered nothing, she tried to act surprised. But of course she wasn’t. She’d watched Horvath wrap the top half of her finger in some paper towels, which he folded neatly and deposited into the right front pocket of his pants. Samantha walked the police to the door and wished them a good night.

Their debt wasn’t completely settled, Horvath had explained. He couldn’t just erase $69,086.37 with a cut. Not just one. But this could count as a kind of payment. Before he raised the cleaver he’d given her a choice: the finger or a $10,000 payment — he’d give her until the end of the month. He’d waited for her to decide, but of course there was no real decision to be made.

Samantha couldn’t imagine going through with it, but already she felt the shock and pain drifting into memory. She even felt a little proud of herself. Horvath was the one who looked squeamish afterward. And when he left she only owed him $59,086.37.

Now, as she got into bed, she held up the wounded hand. The physical pain was bad, but sometimes debt felt even worse. Samantha lifted the other hand. She wiggled all nine and a half fingers: $10,000 for half a pinky. How much could she afford to pay down using this new accounting?

She closed her eyes. Her phone was silent. Soon she fell asleep.