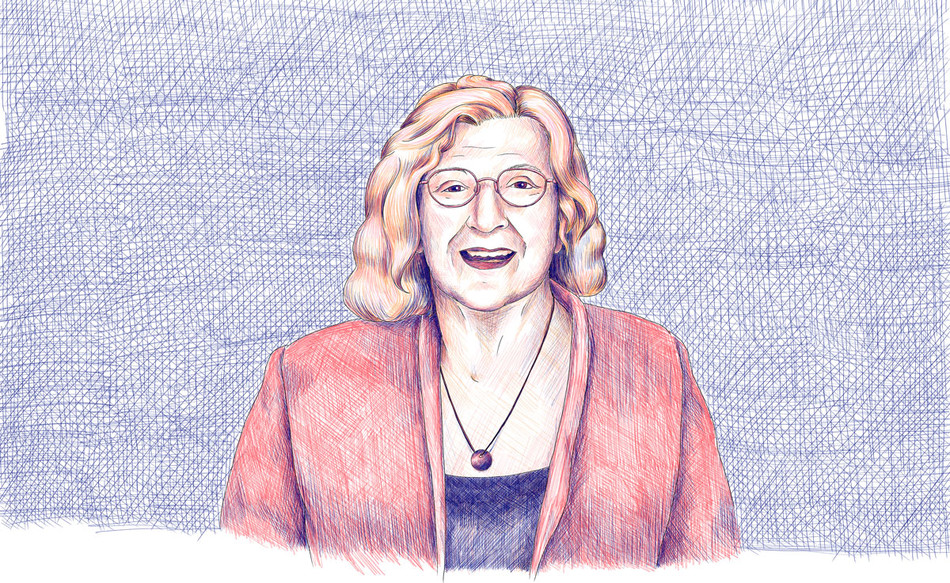

Legendary Child Psychiatrist Clarice Kestenbaum Looks Back — and Forward

At her ninety-fifth birthday party at her Upper West Side apartment earlier this year, Clarice Kestenbaum ’68VPS, professor emerita of clinical psychiatry, was in fine form: energetic, smiling, and talkative. While guests mingled, her son played a ukulele and sang tunes from his mother’s birth year of 1929 (“Just a Gigolo,” “Am I Blue?”). That was also the year that British psychoanalyst John Bowlby, a key figure for Kestenbaum, first considered the effects of parental separation on children.

Ever since Kestenbaum arrived at Columbia’s Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the 1960s, her career has revolved around kids: studying them, treating them, raising them (she has two sons), and training and mentoring child psychiatrists at Columbia. “I couldn’t even count them all,” she said of her trainees. “And each person who learns from me then teaches a hundred other people.” She continues to supervise child and adolescent psychiatry fellows at Columbia for twenty hours a week, conduct peer-supervision classes via Zoom, and consult with patients and families. In 1988, she and Ian Canino founded CARING (Children At Risk: Intervention for a New Generation) at Columbia, which promotes mental health for at-risk youth through arts and education. From 1999 to 2001, she was president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the leading child-psychiatry organization in the US.

“Clarice’s effect on our field is immeasurable,” says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, director of child and adolescent psychiatry at CUIMC. “Learning from Clarice means noticing things in a child or a family that you could never see before. That gift of truly seeing and understanding carries forward to every patient.”

Oh, and she is also David Letterman’s psychiatrist — a fact she revealed in 2017 when Letterman was being toasted at the Kennedy Center as the recipient of its twentieth Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. Somewhere in the program between Jimmy Kimmel and Bill Murray, Kestenbaum walked onto the stage, introduced herself, and joked about what it’s like treating the famous late-night host (“If you ever need a solid forty-five-minute nap, drop in for a session”).

Over the decades, in her papers and media interviews, Kestenbaum has explored many topics in child development, including only-child syndrome (“The only child carries the burden of trying to be all things to all people and fulfilling the wishes and hopes of everyone in the family”); sibling rivalry (“The feelings of the older child are still very diffuse at 12 or 15 months, and he won’t consciously object to a new baby at that time; however, that child will miss a great deal of his mother’s attention and closeness at the time he most needs it”); and the power of narrative to cope with PTSD (“The life story can be changed from one of disturbing, negative recollections to one that highlights positive and affirming memories”).

At her party, she reflected on her profession. Being a good child psychiatrist, she said, “isn’t just about following in the footsteps of mentors. It’s also about understanding a myriad of theories” — her list includes Piaget on cognitive development, the psychosexual stages of Freud, and Bowlby’s theory of attachment based in part on research in geese and monkeys — “and applying them uniquely to each child.”

Kestenbaum’s path to psychiatry was serendipitous. Growing up in Los Angeles in the 1930s and ’40s, she loved to act and play the piano, but the anxiety of being in front of an audience was so paralyzing that her father took her to a psychoanalyst. Under the analyst’s care, she realized that music and theater were not her true calling. When she decided she wanted to pursue medicine, her father was aghast at the thought of his daughter studying the male anatomy. His displeasure was matched later when she took a defiant leap into clinical psychiatry, a field he dismissed as “a fraud.” But her analyst convinced her father to allow it.

Today, Kestenbaum looks back on a field that has changed dramatically since she started: there are many more women practitioners, the use of medication has surged, and “evidence-based” treatments such as CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy) have entered the mainstream. Anxiety and depression are rising, and the effects of the pandemic on young children are only just emerging.

But Kestenbaum has kept both her optimism and her sense of humor: you don’t get to her age without them.

“Look,” she said, as her son sang Cole Porter, “Did we have the Dark Ages? Yes, and then we had the Renaissance. So we’ll go through a dark age that’s pretty bad, and then we’ll have a renaissance. I think the world will change. I’m always very hopeful, and I wish I’ll be here in fifteen years. Maybe I will be.”

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2024 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Children First."