It’s been said that one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, but Charlie Lai ’01SIPA might alter the maxim to say that one person’s trash is a community’s treasure. Or even the beginning of a museum.

Lai, 51, is the executive director of the Museum of Chinese in the Americas (MoCA), which calls itself “the first full-time, professionally staffed museum dedicated to reclaiming, preserving, and interpreting the history and culture of Chinese and their descendants in the Western Hemisphere.” That’s a pretty lofty mission for an institution that began, literally, by the curbside.

In the late 1970s, New York’s Chinatown was in a state of flux. Waves of new immigrants, enabled by the Immigration Reform Act in 1965, took over what had been approximately four streets populated by the descendants of Chinese men who had arrived in the early 1900s and worked in the city’s laundries. And though the Chinatown of the Mayor Beame era was not yet the sprawling mecca of restaurants, fish markets, massage parlors, and trinket and herb shops that would soon appear, it was obvious to many that the neighborhood was changing fast.

Charlie Lai grew up in Chinatown, having emigrated as a child from Hong Kong in 1968 with his parents and five siblings. In 1976, Lai met Jack Tchen at the Basement Workshop, a nonprofit Asian American resource center on Catherine Street. Tchen, the first American-born son of immigrants, had moved to Chinatown from Wisconsin in 1975 in order to work in an Asian American community.

Lai and Tchen began noticing an emerging phenomenon as incoming immigrants moved into apartments vacated by tenants who had died, and new merchants replaced old ones: sidewalk garbage cans were filling up with all sorts of interesting objects — a leather suitcase full of old Chinese slippers, letters written in Chinese from wives back home who were prohibited from joining their husbands in the U.S., store signs, and bound volumes of a local Chinese paper that was emptying out its morgue.

“All of our community’s photographs and artifacts were being tossed out on the streets,” Lai says. He and Tchen started bringing objects home and stashing them in their apartments. What they couldn’t fit, they took to friends’ places. (Tchen stored a seven-by-three-foot sign that said, simply, Chinese Laundry at a friend’s apartment on Morningside Heights.)

By the end of the ’70s, the Chinese population in the United States had nearly doubled to almost a million people, 20 percent of whom lived in New York City. But there was no formally documented history of the community. “It wasn’t as if we could go to the library and find history books about laundry workers,” says Tchen. He and Lai continued going through garbage on the streets, so thoroughly at times that concerned residents would threaten to call the police. But that didn’t stop the two urban archaeologists. Inspired by the history they were uncovering, they started the New York Chinatown History Project in 1980, with the goal of documenting the lives of Chinese in New York City.

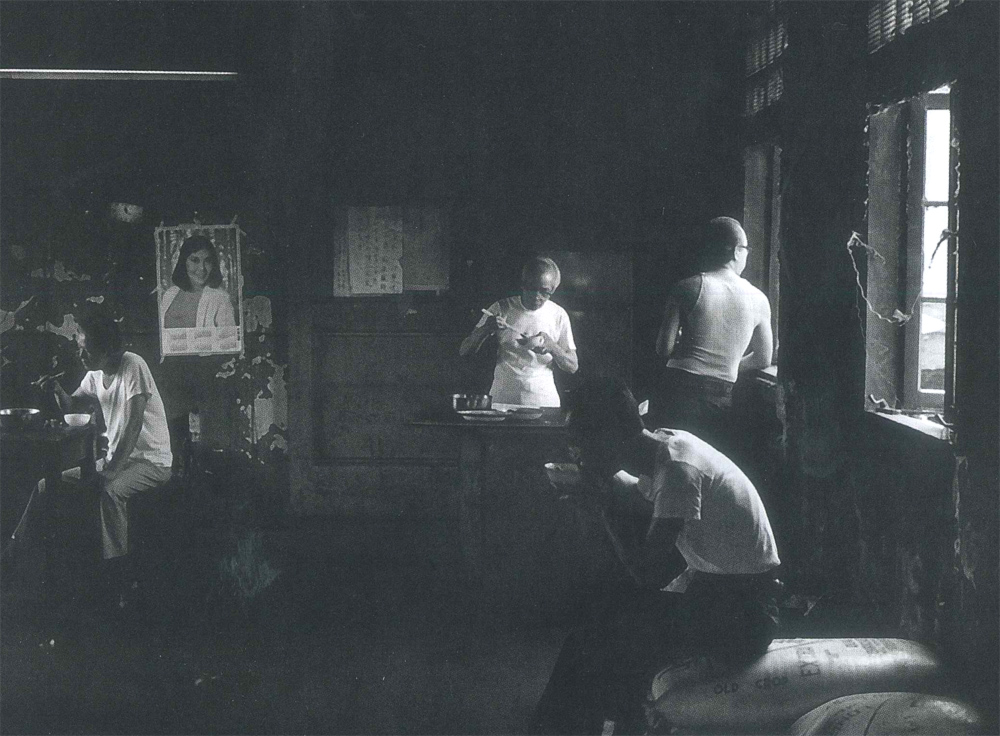

In the mid-1800s, Chinese men were recruited to build railroads on the West Coast, but as miners arrived to dig for gold, the Chinese shifted to laundry work, cleaning miners’ clothing that was so stiff it would stand on its own. “All you needed was a string, soap, and a washboard,” says Tchen, who was a Revson Scholar at Columbia from 1986 to 1987. By the early 1900s, many Chinese had migrated east, and laundry was their main occupation. Using interviews conducted with residents at a local senior citizens’ center, Lai and Tchen mounted their first project in 1980, called Eight Pound Livelihood, about laundry workers. The title refers to the heavy irons used to press shirts.

Distrust was the first challenge Lai and Tchen came up against while researching Eight Pound Livelihood, according to Lai. “These people had lived through periods of extreme discrimination,” he says. “The Chinese Exclusion Act. The anti-communist purges. Their immigration status may have been unclear. Now you had Jack and me, two young guys with a tape recorder, saying, ‘Hey, tell us your story.’” Another problem was the language barrier; Lai is fluent in Cantonese, but many of the seniors spoke a subdialect native to their rural village of Taishan in the Pearl River delta.

Lai and Tchen rented office space on East Broadway between Catherine and Market streets, but instead of holding the exhibit there, they took their salvaged photos and documents back to the senior citizens’ center. This permitted them to fulfill two goals: bringing their work to the community, and using that work to elicit more material. What resonated most for Tchen was how a number of seniors described their lives as “a blood-and-tears existence.” “People started coming up to us saying, ‘This is my story,’” he says. Eight Pound Livelihood soon expanded and in 1984 was shown at the New York Public Library.

That same year, Lai and Tchen relocated the New York Chinatown History Project to P. S. 23, a former school building on Mulberry Street in the heart of Chinatown, which was rapidly growing. Lai and Tchen later took the exhibit to Cornell University, Oberlin College, and Hampshire College. In 1996 a documentary based on the material aired on PBS.

The New York Chinatown History Project was eventually renamed the Museum of Chinese in the Americas, and what had started as a two-man operation has now become one of the nation’s largest museums devoted to Chinese American history, welcoming 100,000 visitors a year.

History on Display

MoCA occupies four rooms in the old P.S. 23 — an office, a collections room, and two gallery spaces for the permanent and rotating exhibits. The permanent exhibit is filled with remnants from Eight Pound Livelihood, including washboards, buckets, and ironing boards, as well as military uniforms from Chinese American soldiers who fought in World War II.

Cynthia Lee ’98GSAS is vice president of exhibits, programs, and collections at MoCA. She discovered the museum as a graduate student at Columbia in 1994, when she was studying the architecture of the Chinatowns of New York and San Francisco. “I had always longed for a place where I could put my own experience into context,” Lee says. “Chinese Americans hear stories from family members, but until you understand the background for that family history, you don’t quite get the meaning of it.” One experience she contextualized was the Chinese restaurant business, in an exhibit in 2004 called Have You Eaten Yet?: The Chinese Restaurant in America. The museum put out a call for Chinese menus, resulting in a witty and poignant exhibition. It demonstrated how restaurant owners adjusted their culture and cuisine to make it more palatable to American tastes, using cartoonish, bamboo-inspired typefaces and inventing such dishes as chop suey. “The Chinese were very pragmatic,” says Lee. “If they had only catered to Chinese tastes, they wouldn’t have been able to make a living, since the Chinese population wasn’t large enough to support their businesses.”

The museum’s programming often lends itself to the neighborhood involvement that has became its hallmark. Fay Chew Matsuda ’71BC, MoCA’s executive director from 1989 to 2004, is most proud of an exhibit called What Did You Learn in School Today?: P.S. 23, 1893–1976, which celebrated the thousands of children of Irish, Italian, Polish, Russian, and Chinese immigrants who came through the school’s doors. The idea arose out of an earlier exhibit that featured a 1930s class photograph. The MoCA staff noticed that visitors would return with more people, bringing them specifically to see the photo. “We realized the picture was a real magnet, and saw what the school meant to the community,” Matsuda says. Inspired by the response, the staff tapped informal networks and put together a broad collection of keepsakes of the school’s alumni — graduation books, report cards, school photos, diplomas. In 1988, MoCA held its first class reunion for P.S. 23, attended by more than 300 people, and has hosted two more since then.

Future Plans

As MoCA’s collections grew, so did its need for space. This year, the museum will embark on a $15 million expansion plan, relocating to the ground floor of a tenement on nearby Centre Street. The new space, designed by Maya Lin ’06HON, the Chinese American architect whose works include the Vietnam War Memorial, will be renovated with glass exterior walls and an interior courtyard reminiscent of her mother’s old home in Shanghai — thus juxtaposing a contemporary feel with traditional Chinese architecture. The space will include a temporary gallery, a core exhibition room, and an auditorium. The project is being supported in part by the September 11th Fund, designated for Lower Manhattan businesses and organizations, and is scheduled for completion next year.

Last September, MoCA brought in Sam Quan Krueger ’05GS as chief operating officer to steer the museum through its ambitious transition. “I call it a cultural and economic development mechanism,” Krueger says of the museum, and stresses that MoCA tells a history relevant not just to Chinese Americans, but to all Americans.

That history becomes more important as China itself changes. “If China is considered the next U.S. rival, things are going to be a little rough over here for Asian Americans,” says playwright and MoCA board member David Henry Hwang. He points to the case against Wen Ho Lee, a Taiwanese-born American scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory who was charged in 1999 with 59 counts of mishandling classified data. In 2000 he pleaded guilty to one count, the other charges were dismissed, and he served nine months of solitary confinement. The case drew criticism from Lee supporters who maintained that Lee was targeted because of his ethnicity. “It’s important to have an institution where we can tell the story of how we have been part of this country and that we’ve contributed to it,” says Hwang, who has been a friend of the museum since the early 1980s, when he turned to the New York Chinatown History Project for research on Chinese railroad workers (the resulting play was called The Dance and the Railroad).

Charlie Lai plans to help MoCA forge greater ties with regional collections around the country, such as Seattle’s Wing Luke Asian Museum, which is associated with the Smithsonian; San Francisco’s Angel Island, located at an old immigration port; and the Chinese American Museum of Los Angeles. “We have good relationships with these sister organizations,” says Lai. “It behooves us as museums to create a much firmer linkage, and to be able to tell the story that is very good locally, but also part of a larger national conversation.”

As MoCA expands it will stay close to its beginnings, maintaining Lai and Tchen’s original mission — preserving and nurturing the community. “One of the biggest needs of the Chinatown community is for people to become part of and to think of themselves as an active public,” says Tchen. “I mean public in a much fuller sense, in which people are becoming citizens, not necessarily U.S. citizens, but citizens of a shared set of concerns and values — and coming together as people.”