When Jack Beeson ’02HON was a student at the Eastman School of Music in the 1940s, he wrote a small piece for piano that he thought was wonderful. It had come to him out of the ether, perfectly shaped! He brought it to his teacher, all smiles, and was promptly told that — notwithstanding a change in key — he had somehow channeled an entire Scarlatti sonata.

I heard Jack tell this story 40 years ago at Columbia when I was one of his graduate students in a composition proseminar. It was an immediate lesson in the power and necessity of editorial review, and in a composer’s being appropriately suspicious of first concepts. Everything was to be tested and retested before being let loose publicly.

My years with Jack came just after the campus sit-ins and antiwar protests, at the peak of the “age of the auteur.” But unlike so many of his European-educated peers, Jack, who was born in Muncie, Indiana, in 1921, was without pretense or grandiosity. This was revelatory to me, since my previous experiences with living composers defined them, almost to a man, as charismatic creators and absolute authorities — Artists with a capital A.

While Jack respected his own musical instincts (tested many times over the years, to be sure), and had already achieved lasting fame with his opera Lizzie Borden (1965), he always remained an approachable and effective teacher. He had an engaged, exuberant teaching style (a model for my own subsequent teaching), and he displayed a respectful yet shrewd suspicion of what the evolving composer might ultimately produce as work of distinction. And if one of us showed him something that really worked, Jack was genuinely delighted.

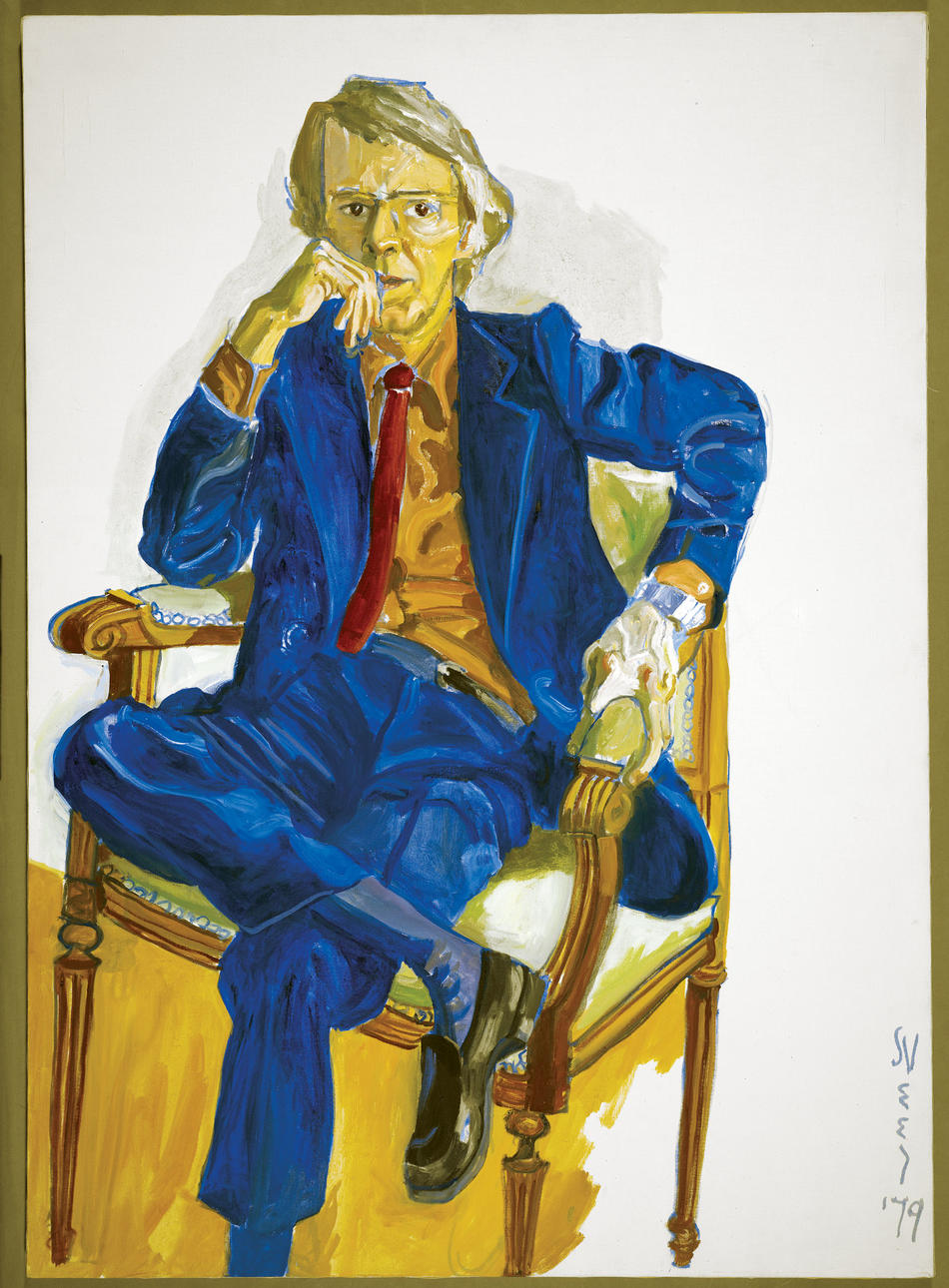

Jack’s music is consonant with his no-nonsense personality and teaching approach. When the prevailing winds of style blew in other directions, Jack, with his bow ties and quiet manner, in many ways remained consistent over the years, from the early works of the 1950s to his last compositions. (His final composition, a short piano piece called “A Fugue in Flight,” was published last year.) It was his innate discretion and artistic good taste — qualities that can so easily suppress emotion — that revealed his musical personality so fully. Whether in his orchestral and operatic works or in smaller vocal and chamber pieces, the music is uniformly on point, clear, and, like the man, at times quite humorous.

Jack is best known for his nine operas, and one reason is his great skill at setting words to music. Throughout his vocal music he is wonderfully attentive to the length of the breath stream, and consequently his reading of the text is characterized by detailed control of a line’s shape, direction, and dynamic. Through altering the periodicity of the harmonic flow — where it pinches, where it loosens — he makes us listen closely. His music is exact.

This past spring, I reconnected with Jack. In May he had been awarded a Letter of Distinction from the American Music Center, and I sent him a note of congratulations. This prompted a surprising phone call to my Arizona home. Jack and I talked about our current projects, and he mentioned that Albany Records had issued a group of his CDs that included new recordings of choral and solo music plus some of the operas. I ordered the choral disc, listened to it, and wrote back expressing the pleasurable discoveries in music not before known to me; and because we’d both set the same poem to music, I enclosed a CD with my setting, plus the two discs of my orchestral music he’d asked to hear.

The final surprise was on June 6 — the day he died, I was to learn — when another letter from Jack arrived. Until that moment I hadn’t known that he’d been on juries over the years that had reviewed my works, that he’d listened to everything and read all the liner notes. In his kind comments, he observes that with both of us, “the choral writing is fluent, well-suited to the voices, and the words very well set.”

“You and I have in common our fiddling with the chosen words & occasionally writing our own,” he added. “What a good idea!” And he concludes: “It was a pleasure to re-meet you!”