When you’re hoping to tap into the mind of a crossword-puzzle constructor and he arrives for your lunch interview wearing a checkered shirt (of course) and tells you he built his first puzzle with his architect mother (of course), you start to think this will be the type of lay-up profile that can be written in pen instead of pencil.

But to truly understand what makes Finn Vigeland ’14CC a prodigy — his first crossword was published in the New York Times when he was eighteen — you must first let go of the natural assumption that his craft is an exercise in simple black-and-white logic. Solve a single Vigeland crossword, like his March 1, 2015, puzzle celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of The Sound of Music, and you’ll see what I mean. You’ll notice how Vigeland deftly weaves the eight notes of the “do-re-mi” scale into eight answers (DOors, thREesome, sashiMI, etc.) and positions them on the grid in diagonal ascending order, mimicking the actual musical scale; you’ll appreciate how he intersects this scale with the answer to “Duo behind [The Sound of Music]” (RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN), a twenty-one-letter solution that perfectly spans the entire width of the puzzle with oh-so-satisfying snugness; and you’ll realize that Finn Vigeland is not a logician but a magician.

Vigeland’s interest in puzzle construction began, strangely enough, with a disheartening discovery he made while watching Wordplay, a 2006 documentary about competitive crossword solving.

“I realized I wasn’t fast enough to be a competitive solver on that level,” he explains. “But I was drawn to the constructors. There was one interview with a constructor in a car, and as they passed a Dunkin’ Donuts he instantly pointed out that if you slide over that first D, you get ‘Unkind Donuts.’ Then he saw the phrase ‘Noah’s Ark’ and said, ‘No, a Shark!’ I remember thinking, ‘Hey, that’s how I look at words and phrases, too.’”

This inspired Vigeland to build his first full puzzle, and with a dauntlessness that only a teenager could muster, he submitted it straight to the world’s most renowned crossword publisher: the New York Times. Vigeland’s puzzle was rejected — deservedly so, he now admits — but Times crossword editor Will Shortz wrote him a personal note that mixed invaluable critique with genuine praise. So Vigeland took a crack at an entirely new puzzle, employing some of the tactics that every expert constructor knows: start with a clever theme; then choose a grid-spanning fifteen-letter (or twenty-one-letter, for the larger Sunday puzzle) “revealer” answer that is linked to the theme; and work off those letters, making sure all non-theme-related solutions, known as “fill,” are fresh and “juicy” — that is, consonant-heavy (Vigeland’s favorite to date is “humblebrag”).

Shortz accepted the new puzzle, and since then Vigeland has been a regular contributor known for the originality of his crosswords. Over his short career he has introduced eighty-two answers that had never before been used in the history of the Times crossword (there are websites that track such things, a testament to the fanaticism of the crossword community). And only once, despite his “soul screaming” at him, has Vigeland had to reach for the life vest of a Roman-numeral answer, the helpful cheat that many constructors use to smooth out a troubling corner of the grid.

Like a writer who sets his novel in his hometown, Vigeland incorporates the materials of his life in his puzzles. His first published puzzle, for instance, paid tribute to his crossword origins, with a shout-out to the New York City school whose crossword club he joined in the sixth grade (HORACE MANN). Then, in an endearing tribute to his first partner in puzzle construction, he tucked in a phrase uttered by so many proud kids reveling in the spotlight: HI MOM.

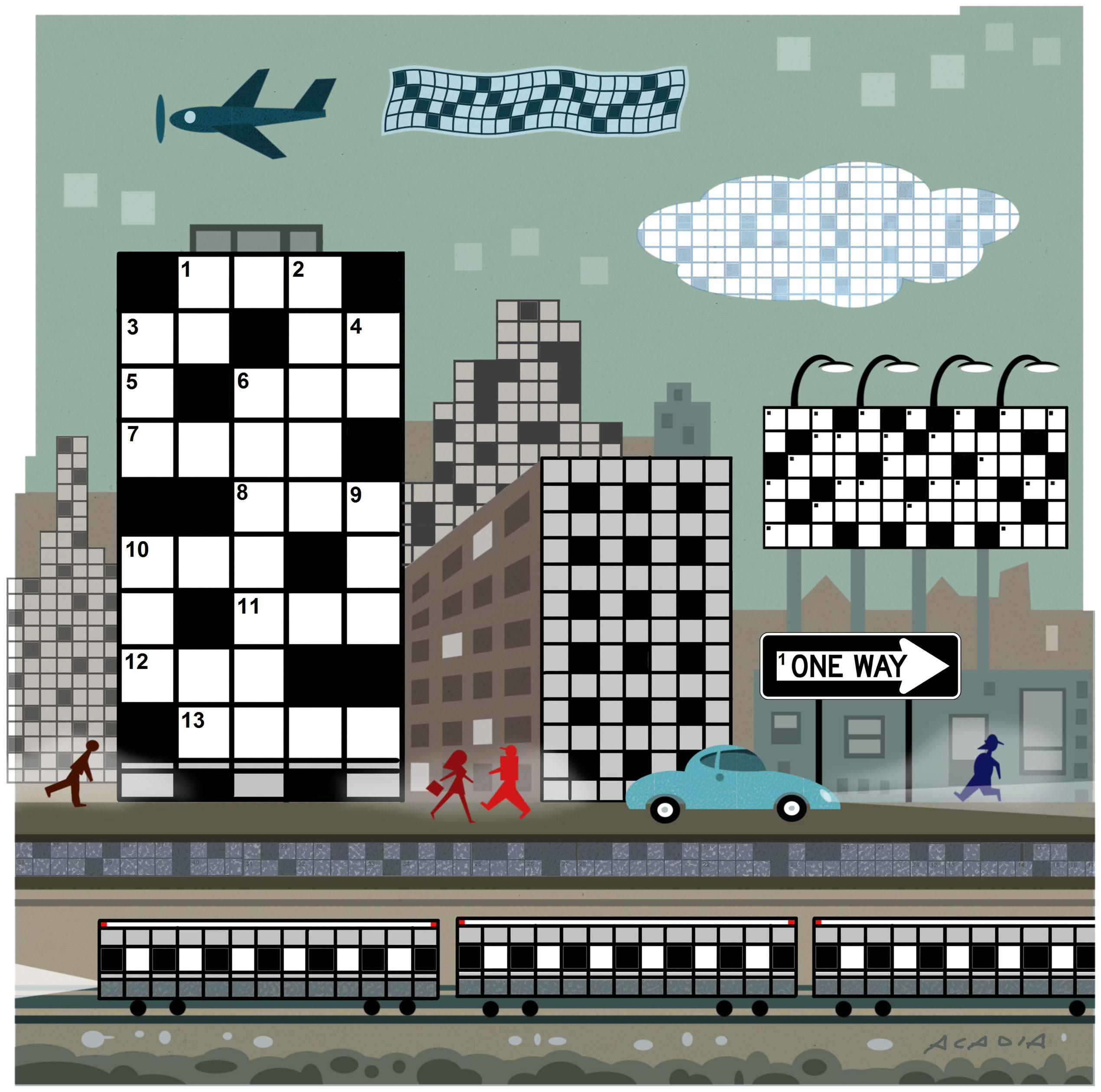

When Vigeland got to Columbia, he majored in urban studies, a reflection of his passion for using diverse, interdisciplinary knowledge to tackle a complex system. Unsurprisingly, he’s enmeshed several references to this discipline in his puzzles, including the surname JACOBS, an homage to his idol, the urban-planning pioneer and one-time Columbia student Jane Jacobs.

As Vigeland reads his lunch menu — at once searching for something tasty and, as always, scanning for a fresh fifteen-letter phrase that could be the theme for his next puzzle — he says he hopes to have a career as an urban planner. He’s particularly keen on improving another sort of grid: Manhattan’s transit system.

Of course, he’ll also continue constructing crosswords. “There’s just no better feeling than the one you get when you finish building a puzzle,” Vigeland observes from our lunch table on Broadway, the 1 train rumbling underneath while taxis zoom past, “and you see this whole grid that really shines as a unit.”