Walking along upper Broadway on a cold Saturday morning, Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson notices a sign in the window of a gift shop. “Life is short,” it reads. “Eat dessert first. —Jacques Torres.” Ferguson pauses to consider the motto from the famous French chocolatier. She scribbles it down on a sheet of paper and continues on her way.

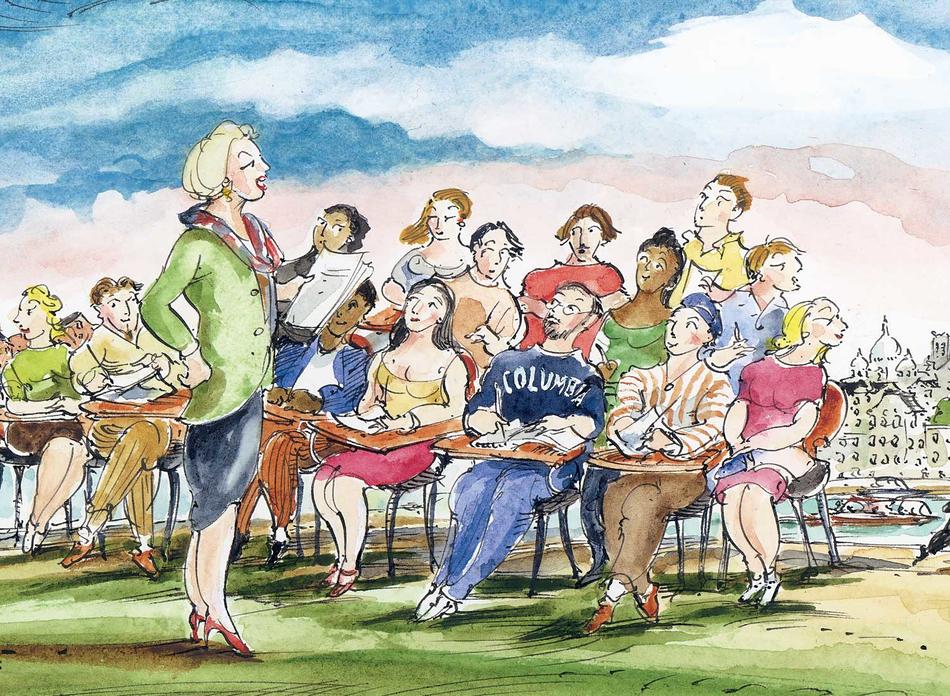

The following Monday, around lunchtime, students file into a lecture room on the seventh floor of Hamilton Hall. As they settle into wooden chairs and pull out their pens (laptops are forbidden), Professor Ferguson reviews her notes at the lectern. On the board is the Torres quotation.

Food and the Social Order, an undergraduate sociology course, is only in its third year. But for Ferguson, food has been a lifelong study — an amour that began, as they often do, in France. “My mother taught me how to eat, and then I went to France and learned more about it,” says Ferguson, who received her PhD in French literature from Columbia in 1967.

Ferguson opens the lecture with the quote. Her tone is straightforward, with a hint of amusement. “What does it mean?” she says, walking up and down the side aisle, her arms folded behind her back. A student offers, “There’s a sense of urgency in it.”

Ferguson then reminds her nearly 50 students of last week’s discussion, which covered the structure of the meal. “The Torres quote assumes you know what a proper meal is,” she says. “But if you looked at Rome in the first century, you wouldn’t have the same sequence of courses as you do today. You also wouldn’t necessarily have dessert, as a last course, associated with sweets.” Students jot down notes. Someone’s stomach growls audibly.

But the course is not just about desserts, or the order of courses in a meal. There’s a rich assortment of topics — from cannibalism to Japanese tea ceremonies, table manners to fast food. “I was studying French, and I noticed food is very salient in a lot of French novels, especially in the 19th century,” says Ferguson, her dangling silver earrings nodding in agreement. “When I moved from French and literature into sociology, I could see more and more the kinds of questions that make Food and the Social Order a sociology course — questions of national identity, production, distribution.”

Krishnendu Ray, a sociologist and professor at New York University’s Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, admires Ferguson’s thorough purview (Ferguson’s most recent book, Accounting for Taste: The Triumph of French Cuisine, is considered a must-read in the field). “In food studies, we use food as a lens to look at social relationships, gender relationships, ethnic mainstream relationships, minority relationships to natives — but we also look at food in particular,” Ray says. “Food matters to us, just as a film-studies person is going to pay attention to the production of a movie. So, even though we do use food as a lens, we also look at the material production of food, its physical nature — which is exactly what I like about Ferguson’s work.”

The issues that Ferguson’s undergraduates write about reflect this connection: a South Korean television show about competitive cooking, coffee through the eyes of a barista, the waiters’ choreography at the restaurant Per Se (and it is choreography — a professional ballet dancer trained the waiters), and High Holy Day celebrations of food in India.

Sometimes, though, it’s hard not to think of food as food. Two dinners in particular stick out in Ferguson’s mind, one in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one in southern France. The cook on both occasions was another American who found her passion in France: Julia Child.

Ferguson smiles as she remembers the meal in Cambridge, which consisted of lamb and sautéed green beans. “You realize, sauté in French means jump,” she says. “And those string beans were really jumping off the frying pan.”

Some food with thought.