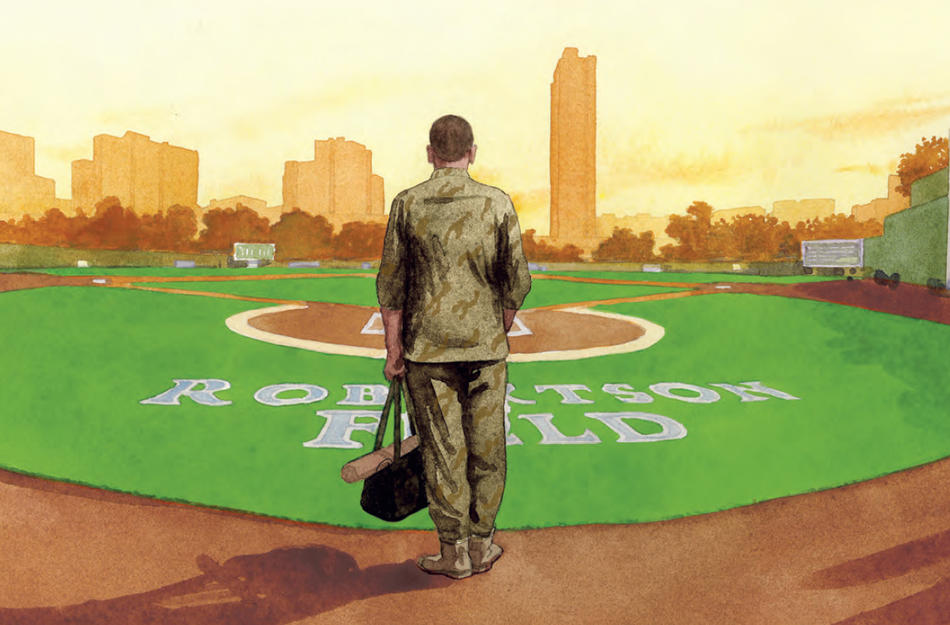

A couple of days before helping to lead the Lions to their first Ivy League baseball title since 2008, General Studies sophomore Joey Falcone sits down in Tom’s Restaurant and asks for “The Lumberjack” — eggs, pancakes, sausage, bacon, and toast. He addresses the waitress with deference, and from time to time, he calls his breakfast companion “sir.” As a former Marine combat medic who served for six years, including two tours of Iraq and one of Afghanistan, Falcone is used to taking orders, not giving them.

“It’s still like that,” he says. “I don’t want to take the classes I want to take; I want to take the classes people tell me to take.”

At twenty-seven, Falcone is the oldest Division I ballplayer in the country. And as a relatively recent arrival on campus — he transferred last fall from the College of Staten Island — the sinewy six-foot-five-inch designated hitter still defers to authority. “I’m newer to the program than some of these other guys,” he says. “So even though I’m older and have seen a little more, when it comes to baseball, I ask them for advice.”

“It’s funny when he comes up to me and asks me about swinging, or about where to study,” says graduating Lion co-captain Alex Black. “It’s like he’s an eighteen-year-old freshman. He fits perfectly into our world. When we do our stretching, he’ll be in the back of the line. It’s not like he’s trying to rise above and lead all of us.”

Falcone has had a great season, batting .333 and leading the team with a .536 slugging percentage. Those are numbers you might expect from a player with Falcone’s pedigree: he’s the son of former major-leaguer Pete Falcone, who pitched for ten seasons with the Giants, Cardinals, Mets, and Braves. Falcone fils maintains that whenever his father talks shop with him, he says only this: “Get the bat head out! Get the bat head out!” The young Falcone laughs. “I’m not saying that’s not sound advice. It probably is.”

Falcone moved around as a kid during his father’s playing days, including a stay in Italy during Pete’s brief tenure in a European league. He graduated from Bolton High School in Alexandria, Louisiana, where, as a right fielder still physically small, he was not a standout. Instead of shooting for an athletic scholarship, he enlisted.

“I knew I was immature,” he says. “I knew I didn’t have any drive to do my schoolwork. I knew that if I graduated and just hung around in the street I’d get in trouble. I had no aim, no interest in college. I wanted to play baseball, but baseball was a thing of the past as far as I was concerned.”

And so he went to war.

“Every time you go on a mission, it’s like Russian roulette,” he says. “You never know who’s going to get hit or who’s going to step on the bomb.” One time it was his friend John Malone, who caught it in the neck in Afghanistan. “He went down, his eyes were open, he was fighting like, ‘I’m tough, I’m going to hang in there.’ But the blood was coming out too quick. Too much, too fast.”

There was also Aiyad Gaab, the bodyguard of a local Iraqi police chief, who was blown up by a car bomb planted under his seat that had been meant for his boss; he lost both legs and some fingers. “Man, that guy took it like a G,” says Falcone, using street slang for gangster or tough guy. “He was hurting, the poor kid, but he was saying his prayers, not knowing if he would make it, and he would see that he didn’t have his legs and he’d say, ‘Oh, man,’ instead of rolling around in agony.”

When Falcone got out in July 2010, he was confused and bitter. He had seen some heartening things — the many Iraqis who welcomed the American presence, the ordinary people who invited him into their homes to escape the heat, the police recruits who responded enthusiastically to training — but as a whole, the experience had simply been too intense.

“I hated everybody,” he recalls. “I was angry at society; I was angry at the world. If people knew what was going on over there, they would never have agreed to a war. If they had seen the casualties, they would have stopped. I was also a medic, so I wasn’t fazed by it anymore. That’s weird. You’re supposed to be fazed by it.”

Determined to “shake my present state as quick as I could,” Falcone enrolled at the College of Staten Island in 2011, where his grades were good enough for his coach to suggest that he apply to GS.

Now Falcone wavers between pursuing nursing and economics. As for baseball, he’s philosophical about possibly turning pro (“I’m certainly open, if it comes my way, to playing at the next level”). What’s certain is that being at Columbia has made the adjustment to life stateside that much easier.

“Getting back to school, being around civilians, being around baseball — that was what helped me slowly but surely put the training wheels back on,” he says, finishing his breakfast. “And the more that I was able to do that, to figure out how to be a civilian, the more I realized, I’m still here.”