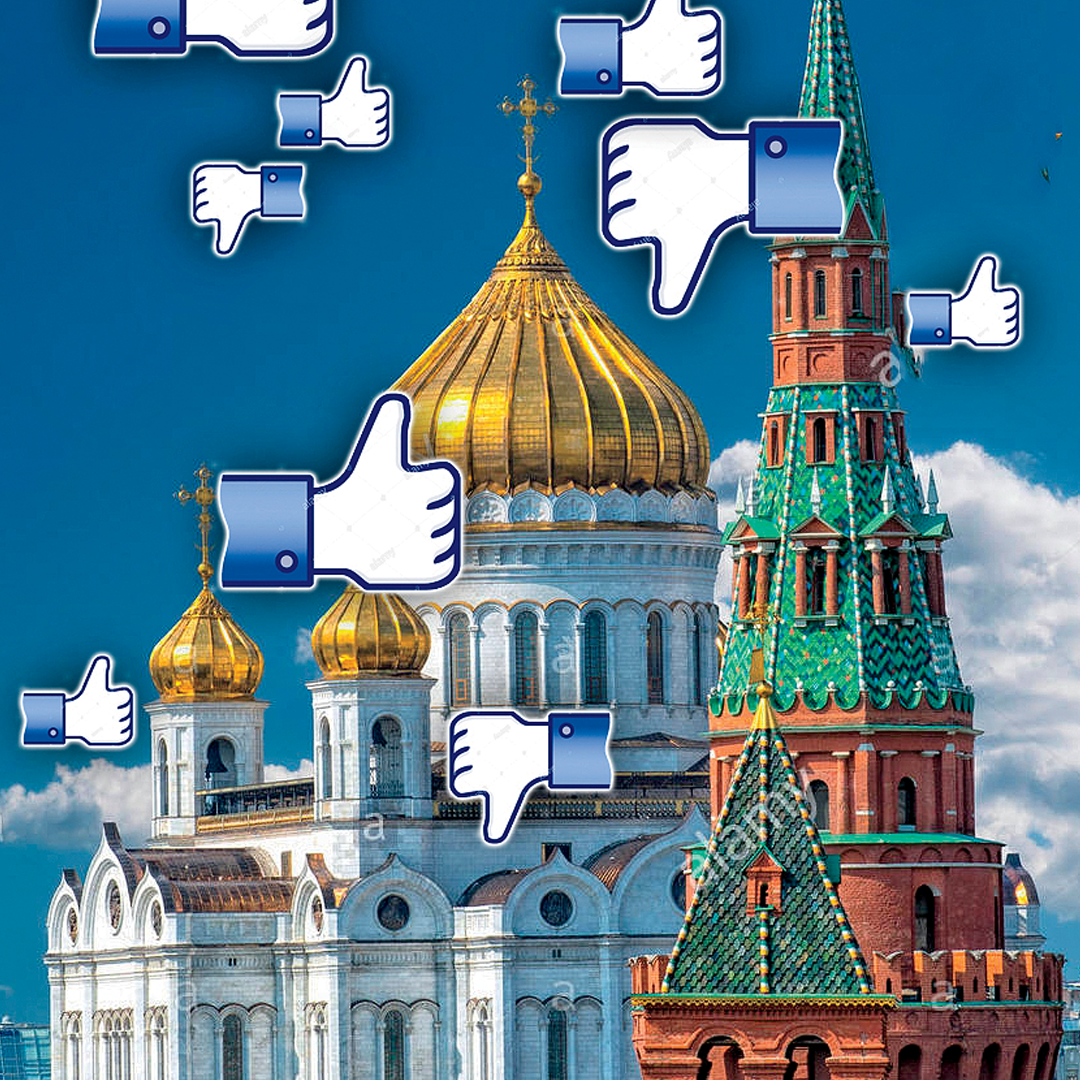

Public scrutiny of Facebook’s role in the 2016 presidential election intensified this past fall when the company acknowledged that political ads bought by Russian agents were viewed by ten million people. Many members of Congress responded by demanding that Facebook be subject to the same FCC rules that ensure that traditional media clearly identify sponsors of political advertising.

But a recent study by Jonathan Albright, research director of the Columbia Journalism School’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, suggests that US lawmakers could face an uphill battle in combating foreign powers’ online propaganda campaigns. Indeed, his study reveals that the campaigns are masterfully exploiting the community-building power of social media.

Albright conducted an in-depth investigation of the online propaganda campaigns in early October. Journalists had by that time uncovered the names of six inauthentic, Russian-controlled Facebook accounts — Being Patriotic, Heart of Texas, Secured Socializing with the Kremlin Borders, United Muslims of America, Blacktivist, and LGBT United — that the company had shut down over the summer. Despite the accounts having been deleted, Albright was able to unearth their content using a social-media analytics tool called CrowdTangle. Specifically, he analyzed the last five hundred posts that had appeared on each of the six pages. He discovered that their reach had been extraordinary, with Facebook users having “liked” or commented on the posts nineteen million times and shared them 340 million times.

Albright also revealed that few of the Russians’ posts before the 2016 presidential election explicitly addressed voting for Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton. Rather, the posts tended to contain inflammatory political statements whose ultimate goal seemed to be sowing division in American society and dampening people’s enthusiasm for voting altogether.

Albright has referred to the campaigns as “cultural hacking.” Russian agents, he notes, “are using systems that were set up by these platforms to increase engagement. They’re feeding outrage — and it’s easy to do.”