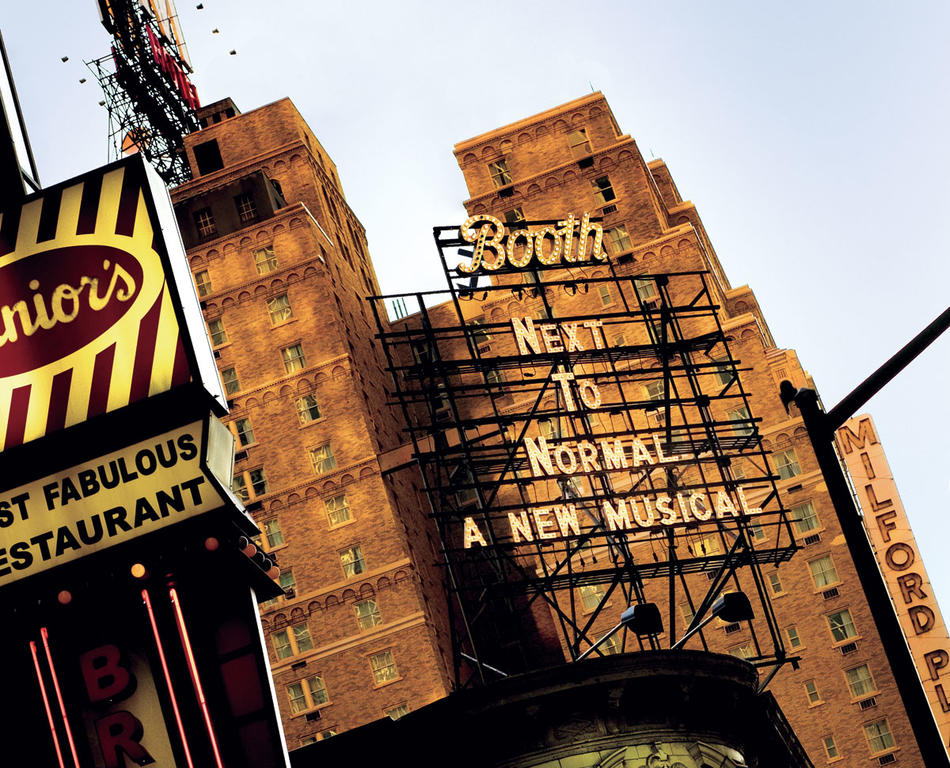

Applause breaks out as the lights dim and a piano plays the first haunting bars. Cheers fill the Booth Theatre, a small Broadway house on Shubert Alley. The actors are ready to perform Next to Normal, a critically acclaimed musical, but the audience — more than 800 people — won’t let them begin: They shout, stomp, and clap, delaying the start of the show for nearly three minutes. The players freeze. Should they try to speak over the tumultuous crowd, or just wait it out?

One day in 1998, Brian Yorkey ’93CC, a 27-year-old writer and lyricist, saw a television news story about a woman undergoing electroshock therapy. He was amazed that such a treatment still existed, and found it curious that it was prescribed mostly by male doctors for female patients.

At the time, Yorkey and his collaborator, the 24-year-old composer and singer Tom Kitt ’96CC, were looking for a story idea. The pair had just won admission to the BMI Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop, a program in which Broadway veterans mentor younger artists. As part of the curriculum, each team was required to write a 10-minute musical. Yorkey told Kitt about the electroshock story, and a lightbulb went off: Why not write a show about a manic-depressive woman going through this experience, and its impact on her family?

It seemed just the sort of bold attention-grabber that might help two ambitious 20-somethings distinguish themselves in a workshop that had boosted the creators of Ragtime, Avenue Q, and A Chorus Line. Kitt, a Long Islander with an affinity for Billy Joel, composed a rock score, and Yorkey, who grew up under the clouds of Seattle, wrote lyrics that blended a poignant story with sarcastic comments about American life and medical science. Feeling Electric debuted at BMI in 1998.

After their foray at the BMI Workshop, Kitt and Yorkey — the names had an auspicious ring that already sounded like Broadway — spent the next 10 years pursuing other projects independently. Yorkey wrote Making Tracks, an off-Broadway musical, penned the adaptation of Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet, and turned out several screenplays. Kitt wrote the music to the Broadway show High Fidelity, based on the film, and also was an orchestrator, arranger, musical director, and conductor on American Idiot, Debbie Does Dallas, Urban Cowboy, and 13.

Yet throughout all of that activity, the two men kept returning to Feeling Electric. What began as a 10-minute snippet about a woman on the edge expanded, at one point, to four hours. The rock-musical score bore traces of Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, jazz, and folk. In a big production number, the woman, Diana, had a nervous breakdown while shopping at Costco. Later, in the searing “You Don’t Know,” she tells her husband Dan that he couldn’t possibly understand the terror of her bipolar disorder — and who she is:

Do you wake up in the morning

And need help to lift your head?

Do you read obituaries

And feel jealous of the dead?

It’s like living on a cliffside

Not knowing when you’ll dive

Do you know, do you know

What it’s like to die alive?

The revamped Feeling Electric had its first reading in 2002 at the Village Theatre in Issaquah, Washington, where Yorkey had worked as a teenager. From there it traveled to New York clubs for individual performances, returned to Issaquah, and then bounced back to Manhattan, where it was performed in 2005 at the New York Musical Theatre Festival, a sampler of new productions. Sitting in the audience was David Stone, producer of Wicked, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, and The Vagina Monologues.

Stone was impressed with Feeling Electric, but he felt the musical needed work. “I asked Tom and Brian if this was about ideas and science, or about people,” Stone recalls. “It wasn’t fully formed. It had a lot of commentary in it, a lot of clever observations, but I thought this show really wanted to be about an entire family in crisis.”

By now, Tony-nominated, Obie-winning director Michael Greif had joined the team, and Broadway veteran Alice Ripley was in the leading role. Greif, whose credits include Rent and Grey Gardens, shared Stone’s concern: “There was a drive to focus more on the family’s pain and less on a critique about the medical establishment,” he says. “But the writers had to want this.”

The writers wanted it. They began revising the show and it opened in February 2008, at New York’s Second Stage Theatre, an off-Broadway house. “What’s impressive is that Brian and Tom responded as a team,” says Greif. “They took this very seriously.”

Kitt and Yorkey had high expectations for the musical, which was renamed Next to Normal, and they hoped it would transfer quickly to Broadway. But critics zeroed in on the show’s internal confusion. New York Times drama critic Ben Brantley was puzzled: “One minute you’re rolling your eyes; the next, you’re wiping them . . . Though it gives off hot sparks of original wit, the show also sinks into what feels like warmed-over social satire, with detours to the giddy brink of camp.”

There would be no Broadway opening with such reviews. Kitt and Yorkey were ready to call it quits.

“One night after we opened at Second Stage, I gathered everyone together to tell them the show would not move directly to Broadway,” Stone says. “Before the meeting, Brian had asked Michael Greif why we should keep doing this, and Michael said, ‘The choice is letting it go or choosing more life. You always choose life.’” It was a pivotal moment, and the creative team came up with an unusual plan: They would retool the musical and find a new theater outside New York. Getting to Broadway was no longer the goal; they wanted to get the show right.

This wasn’t just a question of tinkering with old material and adding new songs. Kitt and Yorkey finally figured out what they wanted to say in Next to Normal. For starters, they axed the big Costco number; Diana’s nervous breakdown now took place at home, giving the scene a more emotional punch. They eliminated the rock song “Feeling Electric,” which had begun to seem like a flamboyant distraction. “Sometimes you have to cut good things,” says Greif. “You cut them for the sake of the show.” The musical was moving further from its original concept: It was now about pain, grief, and loss, with little standing between the audience and these emotions.

The writers’ own perspectives had also changed. Yorkey had been devastated by the collapse of a long-term relationship. Kitt had tasted bitter failure on Broadway (High Fidelity closed after 14 performances), and would soon become a father. He was living in a new world of adult worry, and his musical, which focuses on parents’ anxieties about their children’s mortality, began to reflect it. A show that once confused audiences with its intentions now spoke compassionately about fraying human relationships and the need to confront bitter truths. Although there was no Hollywood ending, it concluded on a note of hope.

The revamped production moved in December 2008 to the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., earning praise from critics. Stone got funding from backers who had previously supported him, and by March 2009 the show had reached Broadway. “Once in a while in the theater you get to say to investors, ‘I need you to do this,’” Stone says. “We simply knew this show was special and had to be seen by a wider audience.”

Driven by surging rock music, Next to Normal tells the dark and unsettling story of Diana Goodman, a suburban housewife whose outwardly normal family struggles to deal with her debilitating illness. Audiences connect emotionally with the characters, including the beleaguered husband, the alienated daughter, and the son who haunts his family. This isn’t exactly The Sound of Music. With scenes of electroshock therapy, attempted suicide, drug overdoses, and marital discord, Next to Normal is closer to the turmoil-ridden dramas of Eugene O’Neill and Edward Albee than to the feel-good American musical.

It’s a quiet Wednesday afternoon, and Kitt and Yorkey are relaxing at a back table in Angus McIndoe, a brick-lined bar and bistro in the heart of Broadway’s hubbub. It’s next to the St. James Theatre, down the street from Sardi’s, and a 30-second walk from the Booth, where a matinee performance of Next to Normal is under way. Kitt, 37, lean and dark-haired, and Yorkey, 39, husky with a bushy graying beard, both nurse tall glasses of iced tea.

“There’s a big difference between being 27 and 37,” says Yorkey, explaining the evolution of the show. “When we were in our 20s, irony was a big thing. Being snarky comes easily when you’re that age and think you’re smarter than everyone else. It’s much more of a risk to open up your heart to something that’s painful.”

Kitt and Yorkey met at Columbia in the spring of 1994. Yorkey, an aspiring dramatist, was determined to get a liberal arts education, and chose Columbia because it didn’t offer the distraction of a theater major. Kitt picked Columbia mainly because it was in New York, where he hoped to get a record deal as a singer-songwriter. Both were involved in campus performance. Yorkey wrote lyrics for the Varsity Show and worked at Miller Theatre for several years after his graduation. Kitt joined the Kingsmen, a popular a cappella group.

One of the Varsity Show’s organizers, Rita Pietropinto-Kitt ’93CC, ’96SOA, who was president of her class, decided that Kitt and Yorkey might work well as a team. Just as a young Richard Rodgers ’23CC and Lorenz Hart ’16JRN had collaborated for the first time on songs for the 1920 Varsity Show Fly With Me, Kitt and Yorkey wrote material for the 100th edition of Columbia’s undergraduate production, which parodied the University’s history. Their first joint effort was a rockabilly song, “The Great Columbia Riot” of 1968:

Gather round, my flowered friends,

As I play my cool guitar.

The oppressive imperialistic racist militaristic school we attend

has gone one step too far.

I’ll tell a tale, my cheerful chums

to make your faces dark —

of plans for an evil gymnasium . . .

in beautiful Morningside Park.

But we won’t just mourn Morningside

and cower down in fear.

Put that gym in Princeton!

We like our small one here.

“They had a chemistry that was unmistakable,” says Pietropinto-Kitt, who married Kitt several years later and is now an actress and chair of the drama department at the Marymount School. “This was the birth of their collaboration.”

Their working style was fluid and flexible. Sometimes the lyrics came first, dictating a musical moment; sometimes music defined a scene, and Yorkey wrote words to match it. On occasion both men sat down at a piano together and wrote songs spontaneously.

Yet for all the chemistry, the two men have very different personalities. Kitt is more outgoing, the kind of person who stays late at a party and loves schmoozing. Yorkey is intense, introspective, and more solitary. “I tend to walk around with a little rain cloud over my head,” Yorkey says. “You might say that I’m a hopeful cynic. But with Tom, there’s an awesome power and light in his music. We’re like yin and yang.”

When Next to Normal opened on Broadway, New York critics responded with stellar reviews, singling out Ripley’s powerful performance. The musical received 11 Tony nominations, and won for Best Actress, Best Score, and Best Original Orchestrations. When Elton John accepted the Tony for Best Musical for Billy Elliot, he congratulated Kitt and Yorkey, saying: “May you stay together and write many more musicals, and be loyal and true to each other.” After 12 years, the odyssey of Next to Normal was “one of the most heartwarming stories on Broadway,” according to Brantley. Molly Smith, artistic director of Arena Stage, said that the show “was reborn, with brilliant surgery. These writers finally located the beating heart at the center of their play.”

They also broke the rules: Next to Normal was not based on a film or book, something many producers are reluctant to take on. It had no bankable stars and was not a family-friendly show. Still, the production recouped its $4 million initial investment, no small feat in a recession. And in a culmination that brought its creators back to Columbia, Next to Normal won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

This November, a national tour starring Ripley will begin in Los Angeles. An Oslo production will be staged in September. Kitt and Yorkey, meanwhile, are immersed in other projects — including a new musical.

On a hot July night, more than a year after the show began its Broadway run, Alice Ripley and two other Next to Normal cast members were making their final appearance in the production, which would debut a new cast the next evening. The prolonged applause that had greeted the actors at the start finally subsided, and the play began. When it was over, the players took their final bows, and received another standing ovation from an audience that included Kitt and Yorkey.

“I looked around at people cheering and suddenly I began thinking about Brian and our work together,” says Kitt. “I remembered how the show began 12 years ago, the challenges, the near misses, and then an overwhelming sense of joy. This was a musical we had always cared about deeply, and here it was, playing in front of this great audience. It all made me extremely grateful, for the show and for our collaboration.”

As Alice Ripley and the cast smiled out at the adoring crowd, Kitt and Yorkey approached the stage to another round of cheers. Holding microphones, they stood with the performers and warmly praised those who were departing. Then Ripley made a brief speech, saluting her fans — and the two men who had made the show possible. “Without you,” she said, “I’m just singing in the shower.”