It’s a short subterranean walk from Roberto C. Ferrari’s office in the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library to the Aladdin’s cave of the Art Properties vault. Here, behind a series of locked doors secured with passcodes, lies a trove of paintings, sculptures, photographs, busts, ceramics, objets d’art, and things not easily categorized. Roman oil lamps. An assortment of elegant old-fashioned clocks. A Chinese ritual mortuary bed.

The more than ten thousand pieces that make up the holdings of Art Properties began accruing in the 1750s, when King George II, who founded King’s College, donated some silver. Since then, all manner of treasure has rolled in. Only rarely does the University seek donations; 90 percent of the art is unsolicited.

Ferrari has been curator of art properties since 2013, the same year he received his PhD in art history from the CUNY Graduate Center. Although pieces can be found in offices and public spaces around campus, Ferrari wants to get more of this hidden art into the open. “We are doing more and more to spread the word and generate interest,” he says.

Display space is limited at Columbia. The Wallach Art Gallery in Schermerhorn Hall (which is scheduled to move to the Manhattanville campus in 2016) offers rotating exhibits, but the University has no large venue comparable to the Yale University Art Gallery or the three Harvard Art Museums. So Ferrari has been sending pieces on the road. Recently, the Lenbachhaus in Munich offered a retrospective of paintings by Florine Stettheimer, many of which came from Columbia’s collection. Last winter, some ancient stone Buddhas were on view at the Nassau County Museum of Art, in Roslyn Harbor, New York.

Students and researchers periodically enter the Art Properties grotto to scrutinize particular pieces. Sometimes Ferrari will present an item at a lecture to illuminate its history. “I’ve seen the excitement on students’ faces when we bring these works of art to classrooms,” he says. In the process, he is receiving an education of his own. “One of the joys of this position has been learning how these works fit into the history of this university.”

The pieces featured here constitute a minuscule glimpse of Art Properties holdings. They are currently in storage, awaiting greater exposure.

Head of a Bodhisattva, c. 550–577

The most significant portion of cultural artifacts in the Art Properties collection is East Asian. Many of these were donated by the psychiatrist and philanthropist Arthur M. Sackler (1913–1987), who had no formal University ties but who did have a passion for antiquities and sharing them. “I’m a lazy, impatient man,” he once told the New York Times with a laugh, “and I don’t have enough lifetimes to be able to make the points that I want my collections to make.” Therefore he built collections with distinct points of view, and turned them over to many institutions, including Princeton, Harvard, and the Smithsonian. At Columbia, he hoped to establish a campus art museum. Given the abundance of galleries already in New York City, however, the idea went nowhere. But since 1964, a small fraction of his gifts have been on display in 207 Low Library, known as the Faculty Room.

Shown here is one of several notable bodhisattva heads from the Sackler Collections, The head is likely from the Xiangtangshan cave temples in China and dates from the Northern Qi dynasty. It measures three-and-a-half feet tall, still bears traces of pigment, and is topped by a crown elaborately circumscribed by motifs of pearls, jewels, and geometric patterns.

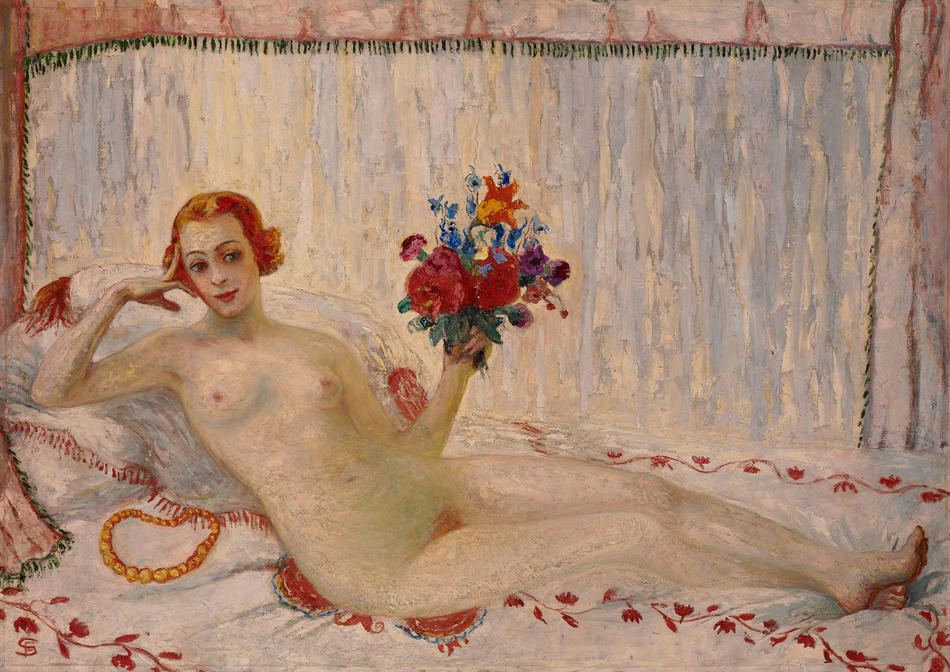

Florine Stettheimer: A Model (Nude Self-Portrait), c. 1915

With more than sixty paintings, drawings, and decorative objects, Columbia’s collection of work by the American artist and poet Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944) is the largest in the world. A one-time student at the Art Students League of New York, Stettheimer had only one solo public exhibition in her lifetime; her work was generally shared in private salons. But after her death, she was the subject of retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Columbia received its holdings through the bequest of Stettheimer’s sister Ettie 1896BC. “There are museums across this country that have only one or two Stettheimers,” Ferrari says. “The vast majority of Stettheimer’s work from our collection is family portraits, landscapes, and still lifes.” This picture in particular is historically significant because in her mid-forties she painted her self-portrait as an “idealized” nude woman.

Charles Willson Peale: Portrait of Alexander Hamilton, c. 1780

Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first secretary of the treasury, was, as some Columbia wags say, “the College’s most famous dropout,” since he abandoned his studies at King’s College after two years to fight in the Revolution. This watercolor-on-ivory miniature is thought to date from the year Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler, and may have been presented to her as a gift. Less than two inches tall and an inch-and-a-half wide, it is set in a framed silk mat (not seen here) that Elizabeth herself is believed to have embroidered.

The artist, Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), was one of the primary portraitists of the leaders of the Revolution; he painted some sixty likenesses of George Washington alone. It was thus appropriate that he immortalized Hamilton, who rose to become Washington’s secretary and aide-de-camp.

Near Eastern Spoon Handle, 8th-7th Century BC

This ivory spoon handle from Iran, carved in the shape of a duck’s head, is part of the Sackler Collections. Simple recurved heads of water birds were sometimes found on spoons and ladles in the courts of Mesopotamia. The duck’s eyes were once inlaid with unknown materials. In 2013, this piece was loaned to Willamette University, in Salem, Oregon, as part of its exhibition “Breath of Heaven, Breath of Earth: Ancient Near Eastern Art from American Collections.” Two other Art Properties items were part of that show: a bronze beaker depicting a lion, and a plaque depicting a hunter and his leonine opponent. (Any reference to Columbia’s mascot was probably coincidental.)

Sending these artifacts on the road was in keeping with the greater goals of Art Properties. “Because we don’t have a museum at Columbia, we use these pieces in a more pedagogical way,” says Ferrari. “We have a unique opportunity to think about using these objects in settings beyond that of a traditional display.”

George Romney: Portrait of David Hartley, MP, 1784

This large painting (58 ¾” x 48 ½”, including frame) of the British member of Parliament who signed and helped draft the Treaty of Paris (depicted on the table) has several Columbia ties. The US signatories to the treaty, which ended the American Revolution, included John Jay 1764KC, the future first chief justice of the United States. The portrait is a bequest of Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, wife of Marcellus Hartley Dodge 1903CC, the eponym of both the campus physical-fitness center and Dodge Hall — as well as a benefactor of Hartley Hall, the University’s oldest dormitory, named for his grandfather, Marcellus Hartley.

David Hartley sat for at least five sessions for this oil by George Romney (1734–1802), whom Ferrari describes as “probably Sir Joshua Reynolds’s chief rival in London for portrait painting.” Ferrari hopes to display the portrait near Reynolds’s painting of Prime Minister George Grenville that hangs in Butler Library. “It would be an interesting companion. I think that the University libraries, which are secure spaces, should feature historical artworks like these. The Romney portrait is magnificent.”

Arry Fenn and M. R. Harder: Columbia University Campus, Morningside Heights, 1903–4

A gift of the banker Isaac Seligman 1876CC, a former varsity rower and a member of the Ethical Culture Society, this watercolor and pen-and-ink bird’s-eye rendering of the north end of the early Morningside campus was executed by two artists. The otherwise unknown draftsman M. R. Harder drew the picture in 1903. The following year, the English-born illustrator Harry Fenn, among the most prominent painters of US landscapes in the late nineteenth century, rendered the scene in watercolor. Fenn’s many engravings and illustrations adorned several books and, frequently, Harper’s Weekly and Scribner’s.

Through the painting, we glimpse Columbia in the first decade of its move to Upper Manhattan. West 116th Street remains a thoroughfare, having not yet been closed off as College Walk. Behind Low Library can be seen the first story of University Hall, which was never wholly built and which was demolished in favor of Uris. And at the corner of 116th and Amsterdam is what is now Maison Française, the last remaining building of the famed Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, which was relocated to complete the quadrangle that is also formed by Kent, Philosophy, and St. Paul’s Chapel.