How should one teach journalism today, and especially photojournalism, when everyone with a cell phone is a potential witness to history? What does the new generation of students need to learn about the modern media landscape?

There is a perception that photojournalists are misery chasers who jump from story to story looking for the next big thing — war, famine, tsunami — and when the action is over, they fly home and wait for the next disaster. That’s last century’s photojournalist.

Today, some of the best photojournalists work more like anthropologists or artists. The most serious ones are taking the long view and spending years on a story, publishing pieces along the way. Sometimes their work is funded by publications, but increasingly it is underwritten by NGOs and foundations, blurring the lines between journalism and advocacy. The model of the globetrotting photojournalist dispatched by New York photo editors to the far corners of the world to witness great moments in history applies only to a handful of working photographers today. Technology has democratized and globalized the industry, which means that breaking- news images are increasingly sourced from Twitter and Instagram, where pictures are shot by amateurs, writers, and local photojournalists already on the scene.

In class, I teach ethics, which is simple, and not. The number-one rule is that photojournalists cannot construct scenes and then pass off the pictures as found moments. Photojournalists observe and frame; the final image cannot contain people or objects that didn’t originally exist in that frame, nor can people or objects be removed from that frame. Everything else — color, saturation, contrast — is largely up for grabs. This is where things get murky.

Image effects are allowed today that weren’t considered appropriate in journalism just a few years ago. Influential photographers, sometimes in collaboration with a photography lab or digital retoucher, champion a style or create an app that is embraced by editors, and before you know it, we’re seeing a million pictures in the press looking the same, regardless of where they were shot or what they capture. A few years back, increasing the clarity and desaturating the color was popular. Now we’re in love with high dynamic range and blazing perfection. Soon it will be something else. I challenge my students to consider how these aesthetic decisions fit into a broader conversation about stereotypes and points of view.

There are stylistic trends in art and in literature, and everyone acknowledges them. But rarely are they cited in photojournalism, perhaps because people still cling to the idea of photography as an objective or neutral medium that captures a shared truth. There is nothing remotely objective about photography. Where I stand, how I got to that spot, where I direct my lens, what I frame, how I expose the image, what personal and cultural factors influence these decisions — all are intensely subjective.

With digital photography, there are so many processing options but little discussion of what those choices tell us about the storyteller and the story. In class we ask, does the aesthetic draw you in to the subject in a revealing and interesting way, or does it overpower the subject? This was a conversation when an almost too perfectly processed image from a funeral in Gaza won World Press Photo of the Year in 2013. What does it mean when an ordinary scene showing a village in Haiti is amped up with a torrent of color and contrast, giving the scene a drama that appears forced? When we see US politicians turned into a cross between Dr. Strangelove madmen and Ringling Brothers clowns, as they were in a recent photograph on MSNBC.com, are we looking at a crude use of black-and-white post-processing or a brilliant commentary on the moral emptiness and vulgar salesmanship that characterizes American political campaigns?

In the old days, a photojournalist might pitch a story to a publication and be sent off for a week, maybe with a writer, and the piece would be published, and it would end there.

Now, publishing might be the last part of a much larger scheme. Stories are projects with foundation and NGO partners; they incorporate social media and data and are seen by the public in the physical world as installations or exhibitions as well as printed pieces.

I’m working this way on something called the Marcellus Shale Documentary Project — six photographers documenting the impact of fracking in states linked by the gas-rich Marcellus Shale formation. Funds came from the Sprout Fund, the Pittsburgh Foundation, the Heinz Endowments, and others. The product is a series of traveling photography exhibitions and artist talks in museums, university galleries, and community spaces in New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. We still publish the work — in Wired, the New York Times, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and others — but truly, the publishing is seen as amplification. So, is it photojournalism? Most definitely.

I’m in the final stages of a project at the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan (opened in 2012 to house Syrian refugees), where I photographed refugee life along with photographers Andrea Bruce, Alixandra Fazzina, and Stanley Greene, all of us from the Noor photography and film collective. We’re printing the images large and then pasting them on two hundred meters of security wall that surround the camp’s entrance. I’ll document the installation, Instagram some pictures, do blog posts, and at some point publish the project. In this case, photojournalism is being used as a conversation within the refugee and NGO community. The project, and the creative process behind it, becomes a way to talk about the larger story of Syrian refugees and their lives in Jordan, and, we hope, makes the refugee camp itself feel less like a penitentiary.

Finally, this May, I’m working with another Noor photographer, Jon Lowenstein, to launch a public-art and media-awareness campaign looking at human trafficking and forced labor in Chicago. One goal is to raise funds to treat trafficking victims. We’re hosting a workshop with other artists, advertising creatives, nonprofit service providers, and law-enforcement officers to make a blueprint for the campaign.

Ten years ago, I never would have thought to work like this. Now, it’s increasingly common, and more and more grant makers are demanding it.

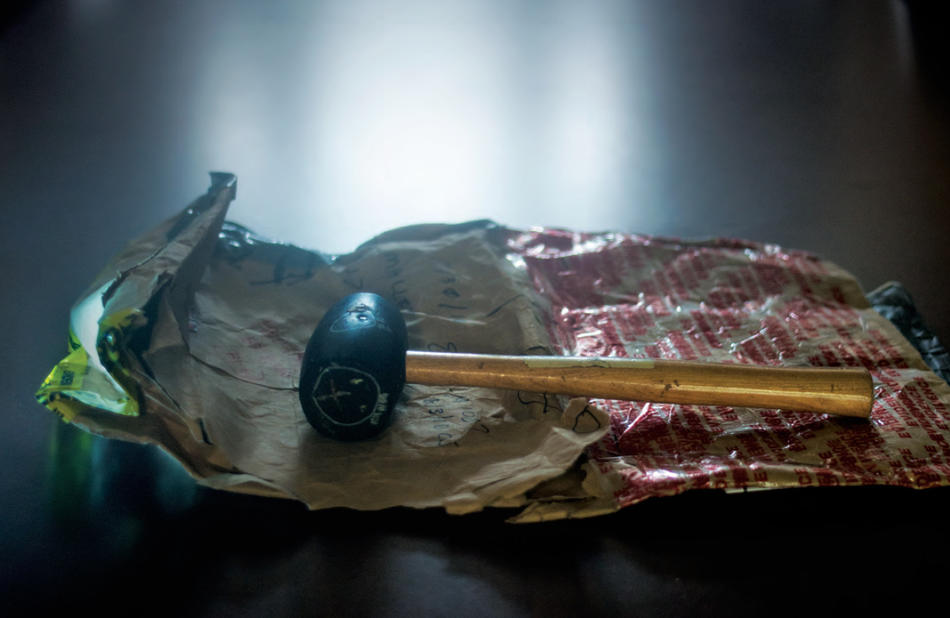

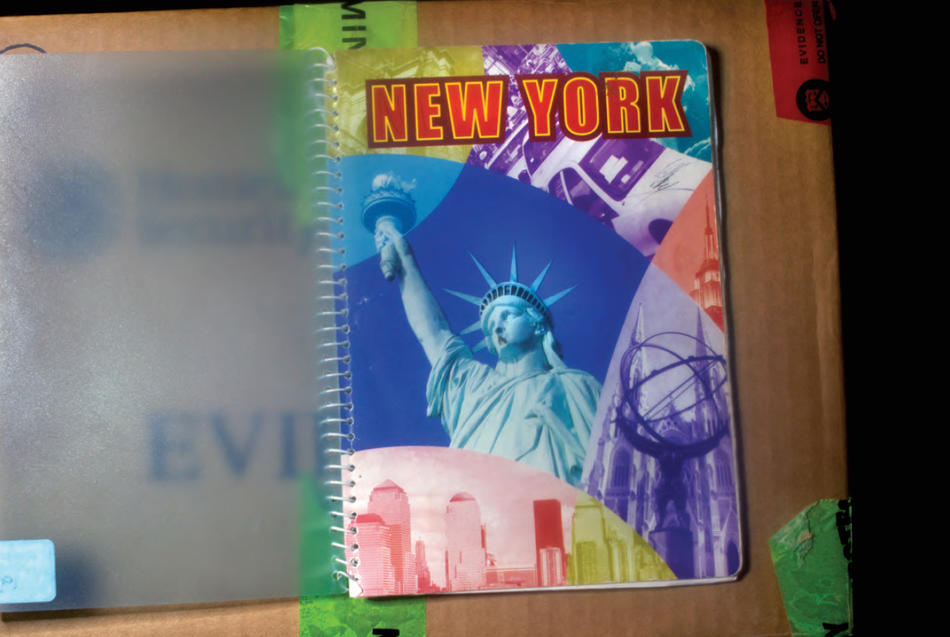

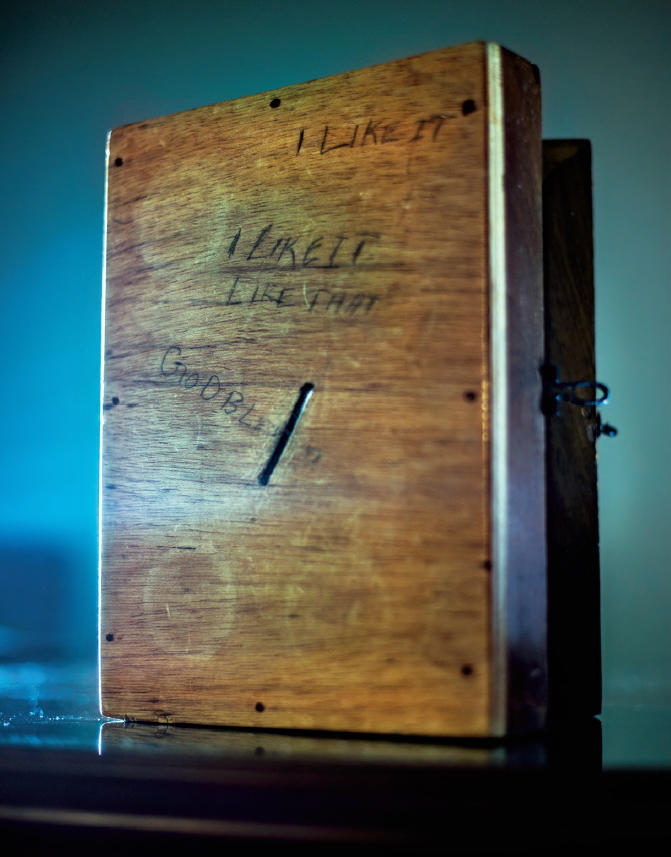

One of the questions we’re asking is, how do you depict modern-day forms of slavery, human trafficking, and forced labor? Should the visuals be only of the victims, which is the norm? I looked at slavery in the United States from the criminal-justice angle, investigating successfully prosecuted cases of human trafficking and forced labor, sexual and otherwise. I photographed trial evidence: a wooden box in which a trafficker kept the tips she confiscated from girls brought from Togo, who were forced to work at Newark hair-braiding salons. (All their earnings, even their tip money, were given over to the trafficker.) I photographed a hatchet in Memphis used to terrorize girls in the commercial sex industry. I photographed texts that perpetrators would force victims to write, submitting themselves to their captors — the rules of labor, so to speak. I also photographed crime-scene locations and survivors. My hope was that by showing the evidence in these cases, I could indirectly reveal the mindset of the perpetrator, which is a new way to approach the subject.

While I was looking into a case in Chicago involving Alex Campbell, a particularly brutal character who was sentenced to life in prison for sex trafficking, overseeing forced labor, and other crimes, Gary Hartwig, the special agent in charge of Homeland Security investigations in Chicago, challenged me to do more with my pictures. He had worked so many really disturbing cases, and the idea that I was coming along with a photo project that promised no tangible change frustrated him.

He voiced an attitude that is running through the photojournalism and documentary- film community worldwide: maybe words and pictures aren’t enough. Yes, do the work, make the images, find new visual approaches, subvert stereotypes, but use the material to make an impact in the world. And do it without succumbing to the predictable narratives of rescue and redemption that make the language of advocacy so limiting. This is the future of storytelling, and this is where it gets interesting.