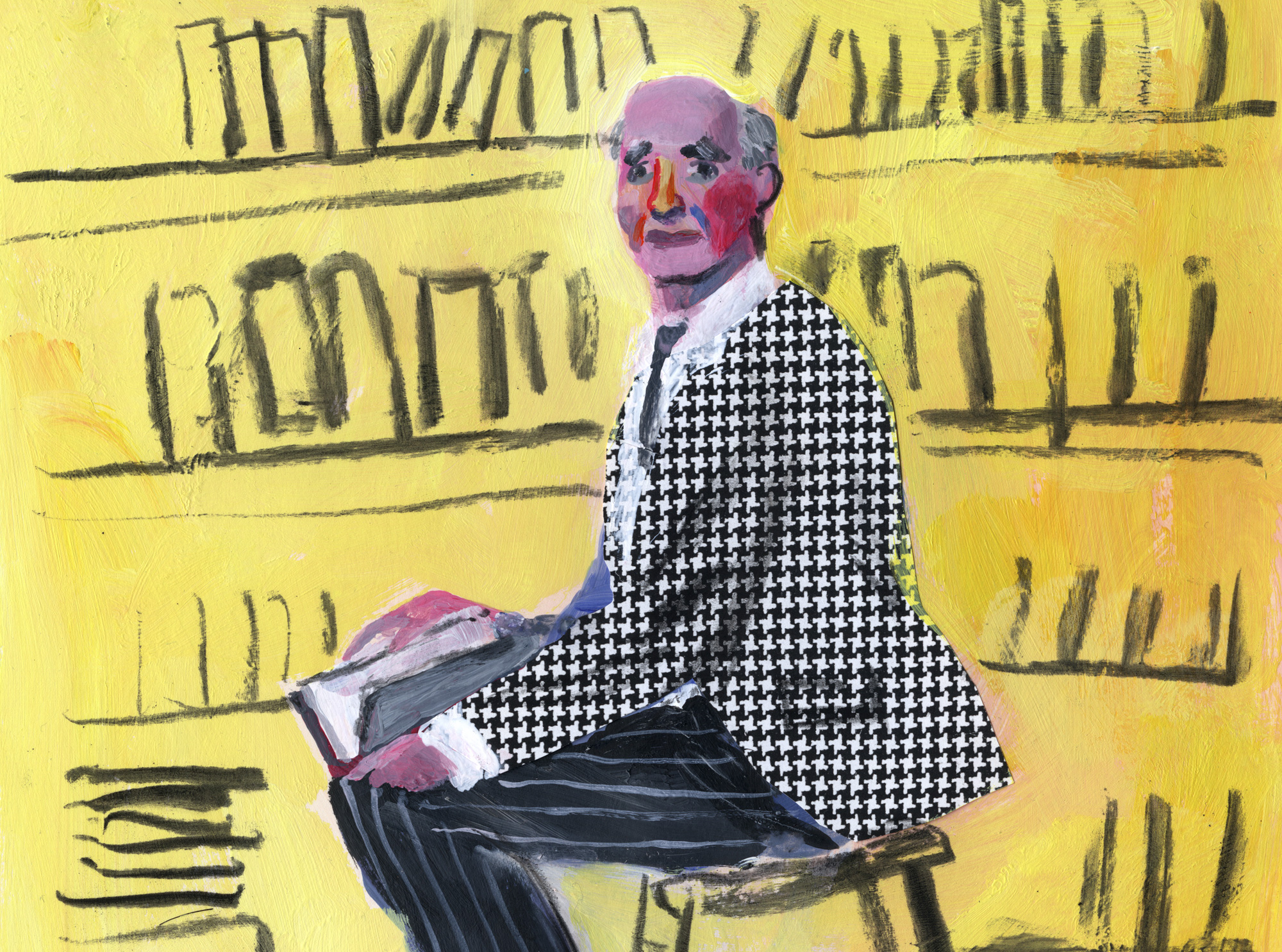

One day in the 1980s, the writer Phillip Lopate ’64CC stood before the bookcase of a vacation home he had rented for the summer, looking for something to read. His eyes fell on a volume by William Hazlitt, and though Lopate wasn’t deeply familiar with the Romantic Age essayist and critic, he pulled the book from the shelf and carried it outside to a hammock. Instantly, he became immersed in Hazlitt’s forthright, conversational voice.

Hazlitt led Lopate to Charles Lamb, Hazlitt’s close friend and a distinguished essayist himself. Both these Englishmen referred often to Montaigne, the sixteenth-century French writer who is credited with inventing the modern essay and giving it its name (which derives from the French verb essayer, or “to try”). “By the time I got to Montaigne,” Lopate says, “I was completely hooked on the form.”

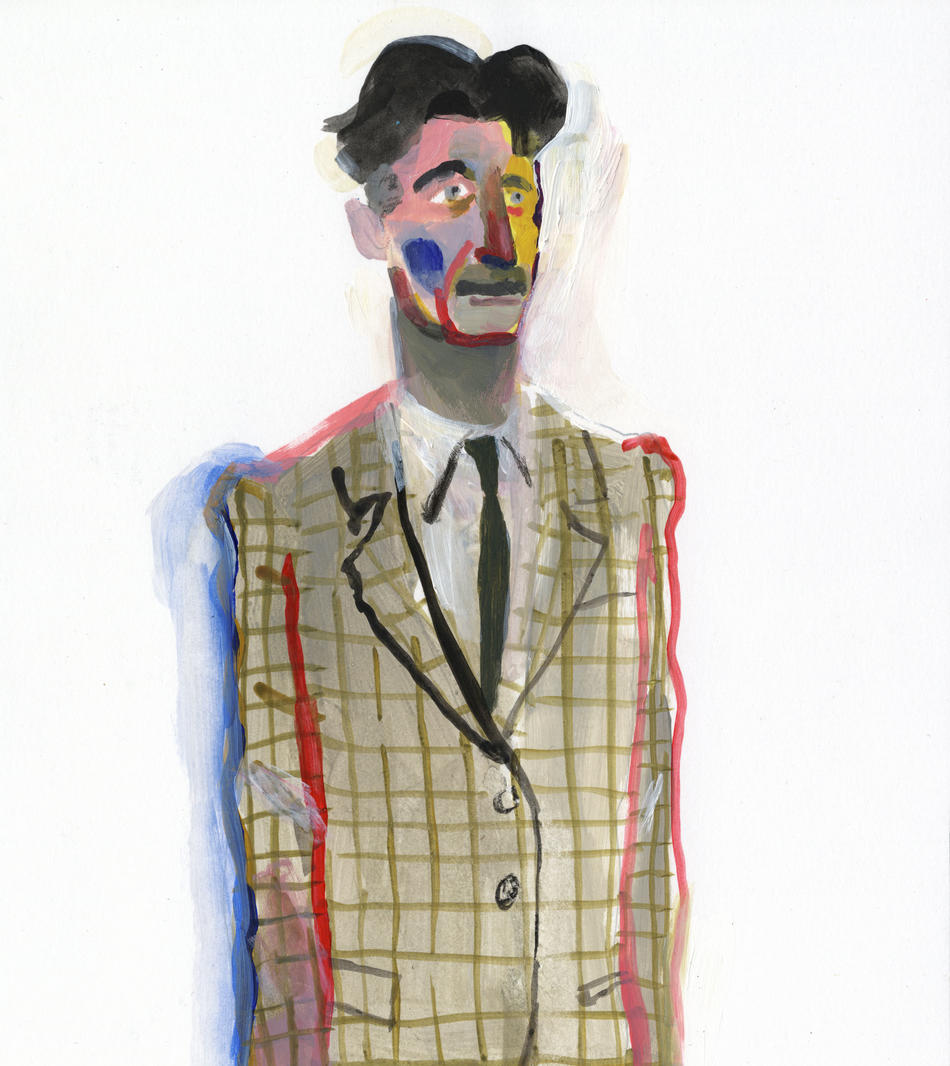

Thirty years later, Lopate, who is the director of the nonfiction concentration in the graduate writing program at Columbia’s School of the Arts, sits in his light-filled four-story brownstone in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, and speaks about the personal essay — the literary form of which he is a leading practitioner, advocate, and connoisseur.

Lopate, seventy-two, has worked hard to get this underappreciated form embraced not merely within the academy (long dominated by poetry, drama, and fiction), but also, perhaps more improbably, in bookstores and on bestseller lists. Meghan Daum, Leslie Jamison, John Jeremiah Sullivan, John D’Agata, and a host of other writers who’ve recently published popular personal-essay collections owe at least a modicum of their success to this man.

Lopate doesn’t disagree with that assessment (“There are far more essayists and the essay is definitely more popular today than it was thirty years ago, and I’ll take a little credit for that”), but he also believes that the genre is uniquely suited to the times we live in. The rise of digital media has brought with it a flood of sharing and storytelling in the form of blogs, and in an era of ever-briefer attention spans, “an essay is short and rarely takes more than an hour to read.”

“There’s also the fact that this form is comfortable with skepticism, doubt, and self-doubt,” says Lopate. “Instead of lecturing you, it invites you into the pathways of the mind of a writer who’s examining, testing, and speculating. As [German social theorist Theodor] Adorno said, the essay isn’t responsible for solving anything. And that suits an historical moment that’s filled with uncertainty and mistrust of dogmatism.”

Lopate had always been fond of first-person narration, both in his writing (fiction, poetry, and the memoir-like pieces he began publishing in the 1970s) and in his reading. “I loved Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground and Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess,’” he says. “The narrator didn’t have to be reliable or even likable; he or she just had to be lively.” So, naturally, when he encountered the confiding, distinctive voices of essayists like Hazlitt, Lamb, and Montaigne, he began to seek out similar writers, for the pure pleasure of their company. His discovery of these past masters of the essay deepened his interest in the form and its roots, and he began teaching the personal essay in his literature courses at the University of Houston, where he was a faculty member from 1980 to 1988. But when he started scouring the book catalogs for an anthology to assign his students, he found nothing suitable. “There were collections of contemporary works, but there was nothing historical, nothing that suggested the canon going all the way back.” Now Lopate had a mission: “It was up to me to produce the anthology I was looking for.”

He got a contract for that collection, and the result, published in 1994, was The Art of the Personal Essay, which takes the reader from the ancient musings of Seneca and Plutarch to the modern ones of Annie Dillard and Gore Vidal. The book has been widely adopted by colleges and universities, for use in survey courses as well as courses that focus specifically on the essay. And thus did this Rodney Dangerfield of genres (“The essay has been considered minor even though it’s an ancient, distinguished form,” Lopate says) assume its rightful place in academia. Lopate’s collection follows the development of the essay as it becomes ever more elastic, expanding to encompass personality-suffused criticism as well as the “new journalism” of the sixties and seventies, as practiced by Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion, and Norman Mailer.

Lopate embraces such eclecticism and is not the least bit doctrinaire in his tastes. In evaluating an essay — whether he’s reading it for work or pleasure — his only yardsticks are his own enthusiasm and the sparkle of the prose. As it happens, his enthusiasms run both deep and broad, accommodating writers as different as Friedrich Nietzsche and Nora Ephron. He asks only that a writer be entertaining and honest. As for sparkling prose, it’s easy to recognize but difficult to define. Nonetheless, Lopate believes it can be broken down into three key components: 1) an element of surprise, in that each sentence ends in a different place than you thought it would; 2) textured language, with buzzes and quirks created by the placement of interesting words next to other interesting words; and 3) a density of thought, with no dumbing down and an implicit awareness of the essay’s long literary tradition.

Still, as catholic as his tastes are, Lopate, like every passionate reader, has certain predilections that lead him to favor some writers and types of writing over others. “We all bring our own backgrounds to our reading,” he says, “and we tend to respond more to work that resonates with our own experience.” Lopate admits, for example, that he cannot fully appreciate even as highly influential and gifted an essayist as David Foster Wallace, partly because he is made uncomfortable and slightly anxious by Wallace’s “confusion and neurosis.” (“There was a lot of nuttiness in my family,” Lopate says.) Although his students look up to Wallace as “this brilliant eccentric, a sort of Kurt Cobain of literature,” Lopate says, “I can’t have that same relationship to him because I’m older than Wallace, and in my own reading I’m drawn to authors who seem wiser than I am. I don’t want the experience of reading somebody who’s tormented. That sounds very narrow of me, but on some level I’m still looking for wisdom when I read.”

He’s also partial to contrarians, and can rattle off a list of favorite works with “against” in their titles: Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation; Joyce Carol Oates’s “Against Nature”; the Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz’s “Against Poets”; Laura Kipnis’s Against Love (“She says love is a kind of bully”); Lopate’s own Against Joie de Vivre. “These are perverse positions,” he says. “How can someone be against such things? But I like these paradoxes because they’re a way of introducing doubt. In a period where there’s a lot of orthodoxy around political correctness, it becomes risky but enticing to interrogate your own prejudices, your own lack of sympathy — to try to tell some truth instead of pretending that you’re universally sympathetic.”

Ultimately, the all-encompassing nature of the essay may hold the key to its staying power. Lopate points to two main traditions in essay writing. “There are the essayists like Charles Lamb, who are always dilating over something daily and minor,” he says, “and then there are those like George Orwell and James Baldwin, who are grappling with the major themes of the day.” Like the novel, the essay can engage with any topic imaginable. “Nothing is off-limits — the essay can absorb theology and science and philosophy, as well as experience. It’s a very capacious literary form, and I believe absolutely that it will endure.”

But who and what, amid a multitude of options, should an eager reader tackle first? Columbia Magazine put the question to Lopate: which six essayists do you recommend that everyone read? Given the wealth of material, limiting Lopate to such a small number seemed almost sadistic. So to narrow the field, we added parameters: stick to modern-day essayists (twentieth and twenty-first century) writing in English, and choose distinct voices that in no way duplicate one another.

Lopate’s final list is a lot like a terrific essay — quirky, unpredictable, and highly individual.

Max Beerbohm

British, 1872–1956

Lopate’s take: For me, wisdom is often found in humor, so I naturally gravitate toward a comic writer like Beerbohm, an essayist who was also a brilliant caricaturist. From my first reading of Beerbohm — whom I discovered after I came across Virginia Woolf’s mention of him as the only true inheritor of the tradition of Hazlitt and Lamb — I found him hilarious, especially in his willingness to portray himself as disreputable or dimwitted (he was anything but) and to push the boundaries of convention, deflate pretension, and expose hypocrisy. And how could I, the author of a book called Against Joie de Vivre, not relate to the curmudgeonly, contrarian persona that Beerbohm often adopts? I’m a big fan, and my hope that he’ll be discovered by a wider audience led me to edit and write the introduction to The Prince of Minor Writers: The Selected Essays of Max Beerbohm, published last year.

If you read just one: “Laughter”

Memorable lines: “A public crowd, because of a lack of broad impersonal humanity in me, rather insulates than absorbs me. Amidst the guffaws of a thousand strangers I become unnaturally grave. If these people were the entertainment, and I the audience, I should be sympathetic enough. But to be one of them is a position that drives me spiritually aloof.”

George Orwell

British, 1903–1950

Lopate’s take: Writing from the perspective of a decent everyman, Orwell tries, in all his autobiographical work, to position his own experience within the larger historical context. And, curiously, everyone finds his own Orwell; he’s a hero to the right and the left, and everyone likes to quote him for his own purposes. “Good prose is like a window pane,” he says in his essay “Why I Write,” and his own style is a model of clarity. Above all, Orwell is notable for his integrity, evident in his unwavering honesty about his own petty or ugly impulses (as in “Shooting an Elephant,” in which he admits to hating both the empire he serves as a police officer in Burma and the Burmese people, who make his life a living hell). With Orwell, the reader always feels that he’s leveling with us. He’s showing us how a decent, civilized person can have these appalling tendencies when faced with difficult options. Like all the best essayists, Orwell moves us toward complexity.

If you read just one: “Such, Such Were the Joys”

Memorable lines: “It is not easy for me to think of my schooldays without seeming to breathe in a whiff of something cold and evil-smelling — a sort of compound of sweaty stockings, dirty towels, faecal smells blowing along corridors, forks with old food between the prongs, neck-of-mutton stew, and the banging doors of the lavatories and the echoing chamber-pots in the dormitories.”

James Baldwin

American, 1924–1987

Lopate’s take: In my view, the Harlem-raised Baldwin (who lived most of his adult life as an expatriate in Europe) is the most important American essayist of the postwar period. And perhaps nothing makes that case more eloquently than his masterwork, “Notes of a Native Son.” As with the best essays, what drives it is the writer’s need to figure out what he thinks. And “Notes” also showcases Baldwin’s trademark honesty and ability to turn himself into a character who comes alive on the page. In it, he braids together the Harlem riot of 1943, his father’s death, and his own young man’s confusions: Does he hate his father? Does he love his father? Is he becoming his father? He juggles all these different perspectives, moving between past and present and between individual psychology and the sociological. It’s a twenty-page essay with the density of a novella.

If you read just one: “Notes of a Native Son”

Memorable lines: “It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength.”

Joan Didion

American, 1934–

Lopate’s take: Didion, a native Californian, came to essay writing through journalism, and her meticulous reporting skills shine through everything she writes. While many essayists flee from the topical, she is attracted to it, drawing fascinating connections among various cultural phenomena of the day, from rock songs to California weather to the Manson Family murders. Regardless of the topic, we want to know what Didion has to say about it; after being bombarded by what all the half-wits are saying, we need to see what a sophisticated eye like Didion’s sees. There’s something poignant in her cool, incisive prose style (Hemingway was a major influence), particularly in her presentation of self — generally as small (a kind of little girl in the corner), timid, inarticulate, and not especially likable. Like Baldwin, Didion demonstrates an invaluable skill of the personal essayist: the ability to make herself a compelling character.

If you read just one: “Goodbye to All That”

Memorable lines: “To an Eastern child, particularly a child who has always had an uncle on Wall Street and who has spent several hundred Saturdays first at F. A. O. Schwarz and being fitted for shoes at Best’s and then waiting under the Biltmore clock and dancing to Lester Lanin, New York is just a city, albeit the city, a plausible place for people to live. But to those of us who came from places where no one had heard of Lester Lanin and Grand Central Station was a Saturday radio program, where Wall Street and Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue were not places at all but abstractions (‘Money,’ and ‘High Fashion,’ and ‘The Hucksters’), New York was no mere city. It was instead an infinitely romantic notion, the mysterious nexus of all love and money and power, the shining and perishable dream itself. To think of ‘living’ there was to reduce the miraculous to the mundane; one does not ‘live’ at Xanadu.”

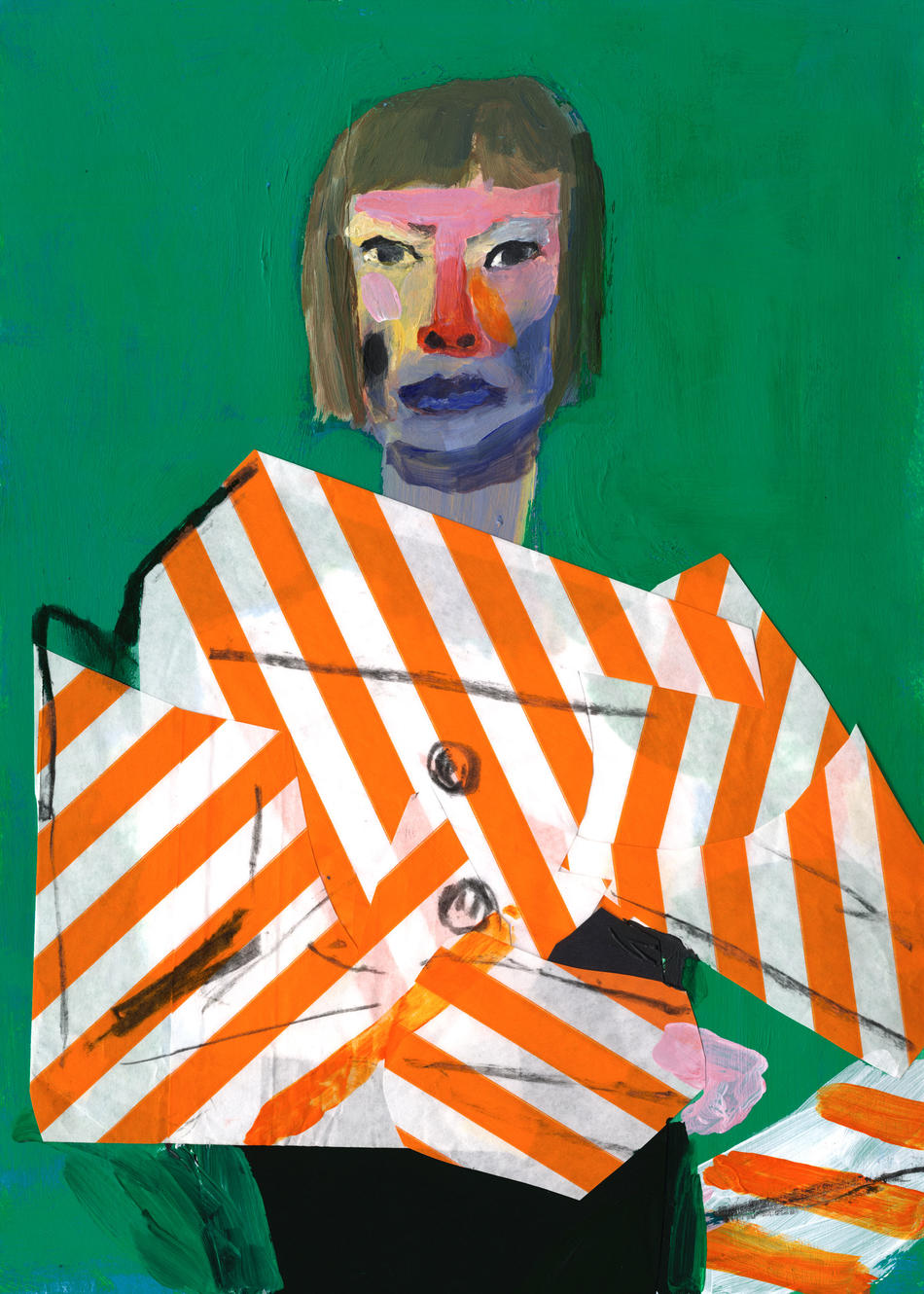

Vivian Gornick

American, 1935–

Lopate’s take: The Bronx-born Gornick, a stalwart of the feminist movement, is a quintessentially urban writer, drawing material for her personal essays almost entirely from the streets of New York City. She’s an American version of what the French call a flâneur, or, in her case, a flâneuse: someone who’s constantly on the street, walking around, observing, and having amusing encounters with strangers. Gornick casts herself as an “odd woman” (her latest book is titled The Odd Woman and the City), who is lonely but stubborn and whose friends have become her surrogate family. She builds her essays out of the fragments she picks up as she wanders around the city. It’s territory she’s perfected and owns.

If you read just one: “On the Street: Nobody Watches, Everyone Performs”

Memorable lines: “They’re in the room with me now, these people I brushed against today. They’ve become company, great company. I’d rather be here with them tonight than with anyone else I know. They return the narrative impulse to me. Let me make sense of things. Remind me to tell the story I cannot make my life tell. I need them.”

Richard Rodriguez

American, 1944–

Lopate’s take: Raised by Mexican immigrant parents in Sacramento, California, Rodriguez ’85GS, ’91SOA documented his gradual separation from their world in his celebrated 1982 book Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez. This acute assessment of what it means to become an American took an unpopular position, because the book basically says that you can’t go back to the old country; you can’t be a hyphenate in America. When you assimilate, you lose your roots. So the minute Rodriguez became a “scholarship boy,” there was a schism between him and his parents. Accustomed to going against the grain — he opposes affirmative action and bilingual education; he is a spiritual person whose peers are secular; he claims membership in an institution (the Catholic Church) that officially condemns his homosexuality — Rodriguez is comfortable with paradox. And that results in a bemused, disenchanted point of view that I find witty, wise, and very reassuring.

If you read just one: “Late Victorians”

Memorable lines: “At the high school where César taught, teachers and parents had organized a campaign to keep kids from driving themselves to the junior prom, in an attempt to forestall liquor and death. Such a scheme momentarily reawakened César’s Latin skepticism. Didn’t the Americans know? (His tone exaggerated incredulity.) Teenagers will crash into lampposts on their way home from proms, and there is nothing to be done about it. You cannot forbid tragedy.”