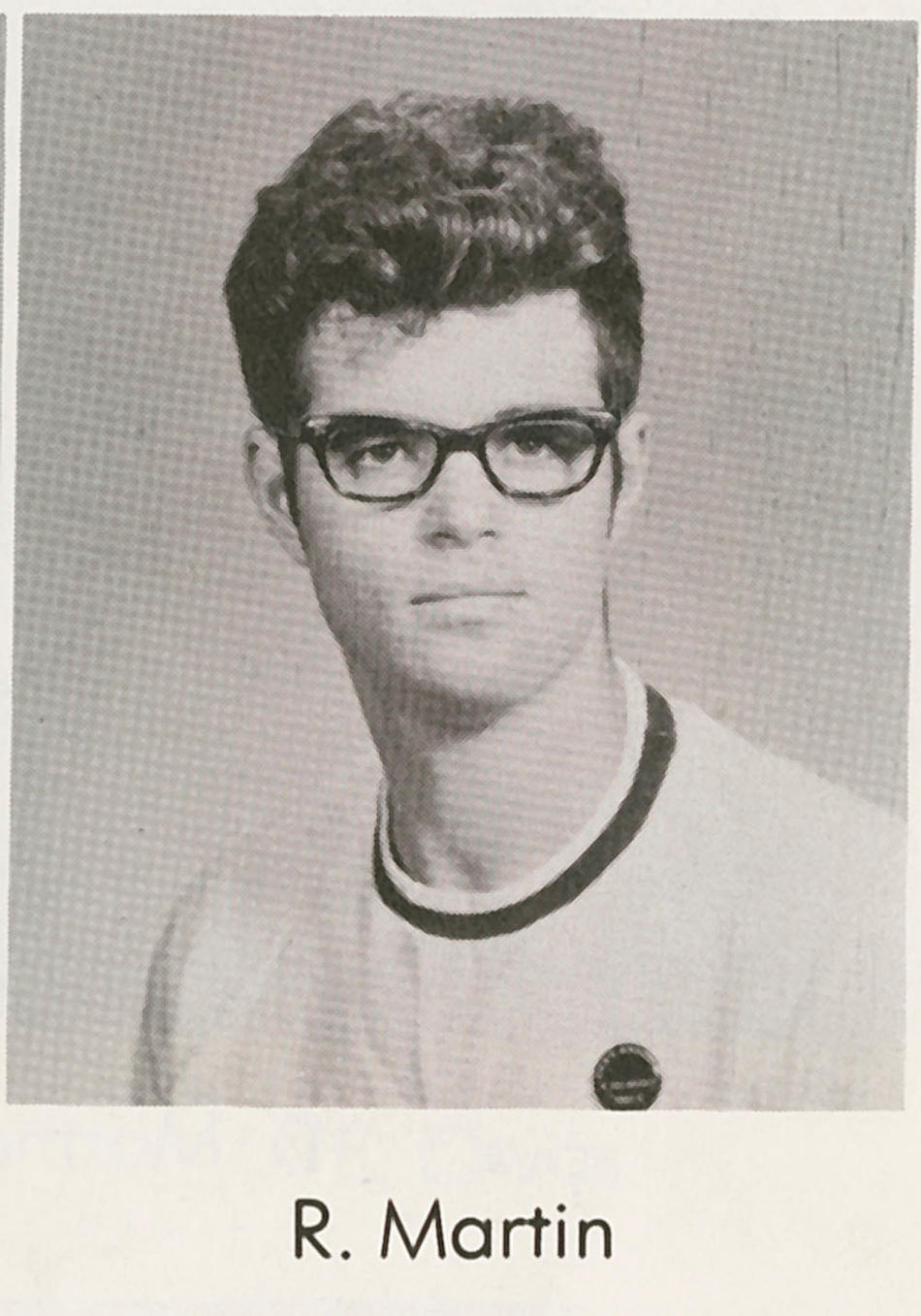

Unlike Dorian Gray, whose portrait festered in an attic, the photograph of Stephen Donaldson languishes underground, framed yet unhung, placed unceremoniously on a tile floor and shoved uncelebrated next to a bookcase in a basement room of Furnald Hall, a century-old dorm on the Columbia campus. Sunshine-yellow walls and Caribbean-blue support beams brighten the room, known for twenty years as the Stephen Donaldson Lounge. Little happens here until Sunday afternoons, when the students of the Columbia Queer Alliance meet. They “vaguely” know about Donaldson. “He started the precursor of our group,” said one, which is true. And he “looks jaunty in his portrait,” which he does — half-Italian, young, grinning and buoyant, his dark curly hair topped by a sailor hat.

The queer lounge, in a delicious historical paradox, actually functioned as a closet for quite some years, a place for the building’s janitors to stash supplies. When the room was posthumously dedicated to Donaldson in November of 1996, its namesake had largely been forgotten. Donaldson surely would have hated that. “He was very self-promoting,” said Wayne Dynes, a friend and former Columbia professor. “And very solicitous of his role in history.” A role indisputably singular: a half century ago, in Columbia’s 1966 fall semester, twenty-year-old Stephen Donaldson, a sophomore, founded the first queer student organization ever on a college campus. Undercover, unofficial, and unfunded — the Columbia administration dithered a while before coming around — but still, the first of its kind in the “whole wide world,” as Donaldson liked to say.

For a man adoring of attention, a glaring absurdity exists. Stephen Donaldson was not his name. But the pseudonym reflected a sensible precaution; in 1966, one rarely revealed his real name in a gay bar, and absolutely never as the de facto president of a clandestine queer club at Columbia University. Donaldson, actually Robert Martin, was interchangeably called Bob, Stephen, or Donny by friends, acquaintances, and lovers, all of whom repeatedly corroborated one thing about him — Martin, the gay activist, wasn’t gay. Not by the rigorous definition of the word, at least. Wildly adventurous sexually, yes. Crazy about men, sure. But exclusively gay — no. “He always claimed to be bisexual,” said Dynes.

Something else about Martin, and this too is completely contrary to his supposed self-aggrandizement: he’d always take the hit, and usually without a shield. “Terrible things happened to him,” said Ellen Spertus, a colleague during the mid-nineties, and now a computer-science professor at Mills College in Oakland, California. “But then he would try to fix the problem. He was always fixing things for the people ahead of him, to make sure it never happened to them.” And as Martin’s activism accelerated, and the fallout landed, the pummeling he took, whether physical or psychological, never stopped him. “Just an extraordinary figure,” said Peter Awn, the venerable Columbia professor of religion who spoke at the Donaldson Lounge dedication. “He fought the culture.”

“That was the thread of his life,” said the Reverend Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Churches, and Martin’s friend from the sixties. “Bob willingly gave of himself to see the movement grow. He was actually a very gentle man. In the weirdest way, he was almost Christlike.”

If Bob Martin was a martyr, consider the following a national act of veneration: in 2016, thousands of LGBTQ student organizations endure on US college campuses. Any university without one is now the deviation; Columbia currently maintains more than a dozen. “Each school has its own group,” said Chris Woods, assistant director of multicultural affairs and LGBTQ outreach. “Like Lambda Health Alliance — that’s the medical school.” Also OutLaws (Columbia Law School), Queer TC (Teachers College), Cluster Q (Columbia Business School), and Q (Barnard College). And then, subcategorizing: GendeRevolution (transgender), Proud Colors (queer/trans people of color), and JQ (Jews). No one knows exactly how many queer students attend Columbia — there’s no data — but educated conjecture suggests at least three thousand, about 10 percent of the total campus population.

“Inclusion is now a core value,” said Dennis Mitchell ’97PH, a Columbia professor for twenty-five years and vice provost for faculty diversity and inclusion. “Today you can’t achieve excellence without diversity.” Or without investment. Mitchell’s $3 million LGBTQ faculty-diversity initiative, a plan to hire four professors focused exclusively on queer studies, is “a very big deal,” he said. “A first. No other university has ever supported a cluster hire of scholars engaged in LGBTQ studies.” The new faculty could be in place as early as the fall semester of 2017.

“This really changes the game for queer students,” said Jared Odessky ’15CC, an LGBTQ advocate and legislative aide to Brad Hoylman, New York’s only openly gay state senator. “The hires are a clear message from the university that this is a priority.” Right now, the school’s LGBTQ classes, though out there, aren’t always available; ferreting out Columbia’s fitful offerings is chancy. “I had to hunt them down,” remembered Odessky. “But now we’re going to see a robust program. This may encourage more Columbia students to pursue research on LGBTQ topics.”

Not that long ago, the notion of any queer academia at all, much less a burgeoning curriculum, was “a joke, just ridiculous,” said Sharon Marcus, Columbia’s dean of humanities. But today, not only do queer students demand the classes — so do straights. “Students are interested in these issues no matter how they identify,” said Marcus. “No one knows what the sexuality of their child will be. They’re interested in learning about sexuality, period.” Although Columbia has no major in LGBTQ studies, the school may offer a minor “as we go down the road,” said Mitchell. That road, he hopes, will leave the other Ivies staring at Columbia-blue taillights: “I’m clearly biased, but I believe we lead on this.”

“Fifty years of remarkable change,” said Awn, summing up a half century of progress. “It represents a triumph of the human spirit. To engage in a battle that no one ever thought you could win. And then — to actually win.”

During Bob Martin’s early years at Columbia, barely anyone was battling; politically speaking, not even a spat had occurred. Nobody dared. Stonewall was still to come. New York’s Gay Pride Parade was nary a figment. Go to a gay bar in the Village and the cops could jail you. Reveal your real orientation at work and the boss might fire you. Open up to friends and most would ostracize you. Disclose to family and they could disown you. Walk down the wrong street and they’d scream out an F-word: fairy, faggot, fruit, flower, flamer. (Or pansy, perv, limp wrist, lesbo, homo, or any of another hundred pejoratives, most far nastier.) More erudite company chose the word “degenerate” — not any better, really — icy, unforgiving, and clinical.

Admittedly, Paul Lynde was spouting double-entendres, saturated with gay subtext, as the amusing center space on The Hollywood Squares; Truman Capote was suitably celebrated for his masterpiece In Cold Blood, which came out about the same time Martin did at Columbia. But otherwise, media depiction of gays, negligible anyway, nearly always portrayed them as frightening, predatory creeps. The Homosexuals, a relatively sympathetic CBS-TV documentary of the time, nevertheless sustained a gloomy and sometimes spooky narrative. From the voice-over of correspondent Mike Wallace: “The average homosexual, if there be such, is promiscuous. He is not interested in, nor capable of, a lasting relationship like that of a heterosexual marriage.”

“We had to keep our sexuality a secret,” said Don Collins, a retired psychologist and a friend of Martin’s. “I would go down to the Village on the weekend and hang out in gay bars. But you couldn’t relax in straight company. They would hate you if they found out. So you would say, ‘I saw the gals in the Village — man oh man, they were hot!’” Collins, who could pass for straight, got by: “You know what the word ‘butch’ means, right? Well, I came from the Bronx, from working-class people. I had a front.”

On campus, queer students were watchful. “Columbia was not a welcoming place,” recalled Dotson Rader, a celebrity interviewer and writer, and one of Martin’s classmates. “If you were openly gay at Columbia, they would send you to a shrink. Or kick you out. The basic attitude was ‘go away.’” Even the school’s queer faculty, always on yellow alert and ruminating about job security, stood cautious. “Everyone knew who was gay,” said Awn, today the dean of the School of General Studies. “But the fear was whether or not it would impact your tenure review.”

“I went to a faculty meeting to evaluate student applications,” said Dynes, who taught art history at Columbia in the sixties and seventies. “Someone would see a photograph and say, ‘This looks like a weak sister.’ That was the euphemism for it.” Presumably queer students weren’t blacklisted, but “the assumption was they would not do well.” Dynes, who is gay, didn’t protest. But the “gossip mill was working,” and he remembered how one homophobic male professor would recurrently scold a female colleague: “He’d say, ‘Why are you hanging around with Dynes? He’s a fag.’ She would say, ‘Well, I don’t know anything about that.’” Later, Dynes learned his female friend was a lesbian.

Against this monolith, Martin hardly appeared a candidate to sling the first stone. Arriving in New York City in August of 1965, he had no money, no friends, and no plan. Friends he found quickly. After all, he was “gorgeous, just a stunner,” said Perry. “With a charisma. When Bob spoke, people would lean in. He could talk about anything. I thought he was one of the smartest men I had ever met.” (Martin claimed a Mensa-certified IQ of 175.) But he was “soft-spoken,” said Perry. “And spiritual. I never saw him hateful with anybody.”

Over the decades, Martin would morph from Quaker pacifist to Buddhist monk. But even he would not declare that Divine Providence drove him to Columbia University at age nineteen. That one’s on Lois, his mother; long divorced from Martin’s father, she lived alone in Miami. Martin tried to spend the summer there, but she ran him off, with her “hysteria over homosexuality,” as Martin put it. He doubted Columbia would take a queer, but a friend called the dean’s office to ask. Columbia said yes, it would. With two stipulations. Commit to ongoing psychotherapy — and promise not to seduce classmates. Martin agreed.

During freshman year he found no gay students or faculty. And his three roommates, with whom he shared a suite at Carman Hall, told the dean they didn’t want to live with a homosexual. The boys tried to be decent, and tendered awkward apologies. But the incident, Martin wrote, was “traumatic.” Columbia assigned him a single room. Now he felt truly alone.

Perhaps nothing characterized his isolation more than this wistful postscript in a letter to a friend: “Now and then, say a prayer for me. There is no one on Earth who doesn’t need it.”

Notwithstanding society’s ever-quickening acceptance of queer — in 2016, coming to terms with your sexuality, while simultaneously coming out to everyone around you, remains an agonizingly lonesome place.

At the Donaldson Lounge, the students of the Columbia Queer Alliance, like Bob Martin, carefully guard their identities. Only four of the ten members interviewed would reveal a first name, and none their surnames.

“They are cautious,” said Chris Woods, who oversees the group. “Oh, yeah. Cautious on Facebook, cautious about who they tell.” Including family members — many queer kids haven’t yet come out to their parents.

“And they have no intention of doing it anytime soon,” said Woods. “Some depend on parents for financial support. What happens if you are disowned?”

Said one student: “I have lots of friends who have been cut off financially. Or the parents say, ‘I’ll pay for college, but after that, don’t come home.’ How do you get through school, how do you live, if your parents won’t pay for your education? It’s a disaster.”

Conversely, and perhaps curiously, a May 2015 survey by the Pew Research Center said most Americans — 57 percent — claim they “would not be upset” if they had a child who came out as gay or lesbian; only 17 percent would be “very upset.”

But that’s a what-if hypothetical. Smacked with unwelcome news in their living room, many parents react with resentment and rage. “They have a lot of expectations,” said Woods. A sense of ownership prevails, as “parents think of the investment they’ve made all these years.”

At the lounge, students readily confirmed family conflict and cutoffs. Acknowledged one: “A lot of us tend to have terrible relationships with our parents.”

Said another: “My dad doesn’t believe bisexuality is real. My mom just believes it’s a phase.”

And another: “I told my mom when I was a senior in high school. She told me she should have sent me to church when I was a kid. I never brought it up again.”

Just ahead for Columbia’s queer students is graduation, which today carries a new risk — job hunting while out. As described in a January 2016 study published in Socius, a journal of the American Sociological Association: a researcher sent a pair of fake résumés from fictional women to more than eight hundred employers. One résumé listed membership in an LGBTQ student organization. The other did not. Those with the queer distinction received 30 percent fewer responses.

“For graduates going out into the world, it’s an eye-opening experience,” said Adam Nguyen ’98CC, president of the LGBTQ alumni group Columbia Pride. “Your self-expression may not be easily accepted.” And even after you get the job, you’re not always sheltered. “There’s subtle, day-to-day discrimination,” he said. “Like not being promoted. Not being staffed on certain projects. ‘Is so-and-so too flamboyant to meet a client?’” That’s “prevalent,” Nguyen said, even at companies with nondiscrimination policies in place.

“The fight is not over,” said Troy Perry, alluding to the same-sex marriage victory in the US Supreme Court. “Now we’ve got to fight for everything else.” Perry, along with many LGBTQ leaders, contends the win induced a drowsy languor; that within the queer community there lolls a widespread conceit — that marriage is not just a milestone, but a capstone. “In other words, ‘Now we have same-sex marriage, so we’re done,’” said Nguyen.

But in twenty-eight states, gays and lesbians don’t have full job protections. A queer couple can marry on Saturday, share wedding photos online Sunday, and be terminated by a social-media-savvy yet homophobic boss on Monday. Not only is the movement not over — perhaps it has not even entered the endgame. Perhaps, in too much of the queer community today, the battle is not only about discrimination from the outside — but disengagement from within.

“We’re not under siege anymore,” said Peter Awn. “So we’re not all that well-organized anymore. The perception is that the battle is won. And that’s a shame.”

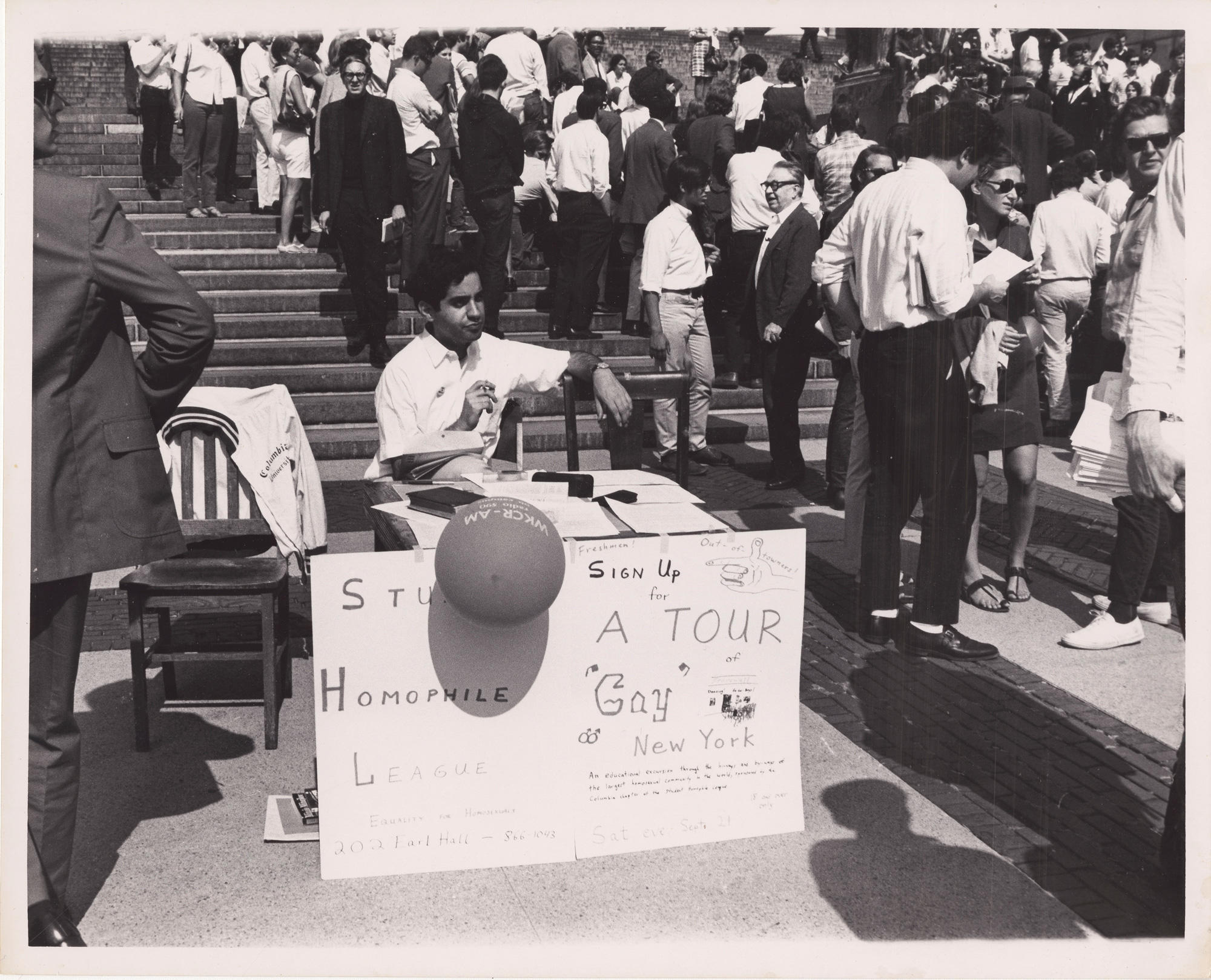

October 28, 1966, was the “birthday,” as Bob Martin called it, of Columbia’s Student Homophile League. But in lieu of a party that Friday afternoon, a rather twitchy engagement was held at Earl Hall, attended by two dozen of the school’s administrators and mental health counselors. All had assembled to absorb a mortifying announcement: the world’s first homosexual student organization was starting, right there, at Columbia. Granted, the group was tiny — early on, there were maybe three members, scarcely enough for the school’s skeptical bureaucracy to take seriously. But Martin had procured a formidable sponsor — the University’s controversial chaplain, the Reverend John Cannon, a straight Episcopal priest. “Our lightning rod,” wrote Martin. “He put his own neck on the chopping block for us.” As for the Earl Hall meeting: “A lively debate.”

From the outset, Martin knew the trickiest part would be finding members for the organization. Plenty of homosexuals were on campus, certainly, but very few ever bolted from the closet. Martin had met another gay student, Jim Millham ’67CC, a psychology major; Millham, in turn, pushed several highly disinclined gay classmates to join up. (“Keep us out of it” was the initial response.) Superstar students were recruited, whatever their orientation — popularity and clout were what counted — and a few went along. “Seems to me I signed a paper that made me a member,” said Dotson Rader, who then identified as bisexual. “But I don’t remember going to any meetings.” Two straight women from Barnard enlisted; Martin, though more into men, briefly dated one of them. “And I wanted to pursue the relationship,” said Seana Anderson. But when Martin sat her down to explain he liked guys too, Anderson made it easy. “That’s OK,” she said. “Let’s just be friends.” Named group secretary, Anderson then conscripted her roommate, Carol Mon Lee; that was easy too. “Seana and I didn’t have a big conversation about it,” recalled Lee. “I just said, ‘Sure, of course, I’ll help any way I can.’” Already, both women had been energized by the escalating women’s movement, and Anderson was immersed in “civil rights and freedom rides” while in elementary school. With that background, signing on with a queer organization didn’t seem much of a stretch. “Anyone who was oppressed,” said Lee. “To us, it was all relevant.” The stitched-together alliance now had about ten members.

Not a few administrators envisioned alumni contributions hitting cement. Others wondered about government harassment. Surely the FBI would deem any homosexual organization subversive. But Columbia’s Committee on Student Organizations, charged with conferring recognition to campus groups, was receptive to Martin’s request for a charter. There was one caveat: provide a membership list — and no pseudonyms, please. That was a sticking point; nearly everyone rankled at identifying themselves publicly. Martin demanded anonymity. “Bob thought it would be dangerous to give them our real names,” said Anderson. Six months of wrangling followed until the school relented. Their identities would remain confidential.

When Columbia granted approval on April 19, 1967, Martin instantly dispatched a press release to every media outlet he could think of, and received nearly no response at all — just a brief interview on WNEW, a New York radio station, and a front-page article in the Columbia Spectator. Not much else happened until May 3, when the New York Times sniffed out the story and slapped it on page one. Now, suddenly, everyone noticed. “All the papers, all the TV stations, all the radio stations,” wrote Martin. “The next couple days were frantic as media — which had ignored the press release — suddenly wanted the information I had already given them.”

If October 28, 1966, was the group’s birthday, then May 3, 1967, was its baptism. The story went worldwide. Columbia administrators were horrified by the publicity; a homophile organization was “a quite unnecessary thing,” said one, “and sure as hell won’t help” funding or recruitment. Sacks of mail — fuming, hysterical — arrived at the school. Martin was not displeased. “We were celebrities,” he chortled. And already he had a vision: “I saw Columbia as the first chapter of a spreading confederation of student homophile groups.”

That’s exactly what happened. Within two years, Cornell, NYU, Stanford, MIT, and Rutgers, inspired by Columbia’s daring, established gay organizations. Within four years, about 150 queer student groups had launched on college campuses. And at Columbia, within a few months of the Times article, much of the initial controversy had subsided. As Martin noted: “All my friends know about me now, but I have not encountered any hostility yet.” A penniless outcast had kindled a global movement.

But commingling with Martin’s ceaseless crusading was a swiftly accruing tax on his psyche. A couple of years following the commencement of the Student Homophile League, Dotson Rader was visiting Cowboys and Cowgirls, a gay bar in Manhattan. There he saw Martin, in a sailor suit. Rader brought Martin to his table and introduced him to Tennessee Williams the Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, and Rader’s companion for the evening. Martin stayed about fifteen minutes, long enough for both men to notice something peculiar. “Bob had a resentment, an anger inside of him,” said Rader. “I had the sense he was walking on the edge of hysteria. Tennessee didn’t like him.” Indeed, when Martin departed, Williams lyrically opined that Martin was “a collector of grievances.” He seemed “so twisted by abuse,” said Rader, “that all that was left was victimhood. He took on victimhood as an identity.”

Martin graduated from Columbia in 1970 with a degree in political science, and straightaway joined the Navy. (“He told me he went in because of all the beautiful men,” remembered Anderson.) In 1971, the Navy kicked him out for “suspected homosexual involvement”; he fought six years before getting an honorable discharge. In 1973, police arrested him in front of the White House during a Vietnam War protest; he was put in a cell called “the playground,” where dozens of prisoners took turns raping him. (“Forty-three times,” said Perry.) Martin went public with the hideous story and made national news.

Then, in 1980, what Martin characterized as “the last straw” — actually, a staggering act of self-detonation — unspooled at the VA hospital in the Bronx. Seeking treatment for a sexually transmitted disease, he was turned away by the attending physician after a four-hour wait. Martin went home, drank “two tall glasses of straight liquor,” returned to the hospital, pointed a loaded pistol at the doctor’s throat, and demanded a penicillin injection. “I don’t want to hurt anyone,” he said. “I’ll surrender as soon as I get treated.” They convicted him on six felony counts, including kidnapping and attempted murder. Sentenced to ten years, Martin got out in four. He described his folly as “a revolt against the system.”

Martin always said prison gave him HIV. Even in his last years, he occasionally submitted to interviews on television talk shows to detail his gruesome jailhouse experiences. “So we bought him a suit at Bloomingdale’s,” said Ellen Spertus. “By then he had a big middle and his hair was gray. You could tell he had a rough life.” Martin had little opportunity to wear the suit. AIDS killed him a few months later, in July of 1996, about a week before his fiftieth birthday, and four months before the dedication of the Donaldson Lounge.

Throughout much of his life, Bob Martin suffered from depression, insomnia, and panic attacks. As did his mother, Lois. Somewhere along the way, between his battles, they reached out to each other. The son wanted reconciliation. The mother needed absolution. What she had done, he forgave; what he had become, she accepted. They resurrected their relationship. Martin saved her letters until his dying day. “I hope very much you have love, Cheri,” she once wrote. “Always I hope that. I don’t care what kind. As long as it’s love.”

Acronym Acrobatics

Even those who resolutely cling to the lumbering acronym LGBTQ readily concede its linguistic clumsiness. Unmemorable, unpronounceable, unhitched from vowels, and untethered from cadence, the ungainly LGBTQ serves our syntax as a shorthand for the spectrum: L (lesbian), G (gay men), B (bisexual), T (transgender), and Q (queer or questioning, your pick). Hence, the acronym’s singular virtue — inclusiveness. Supposedly, LGBTQ, an earnest if inelegant cipher, embodies the entire rainbow community.

“LGBTQ attempts to be inclusive, and I applaud that,” said Marcellus Blount, an associate professor of English and African-American studies at Columbia.

“But it’s still imprecise.”

Imprecise, because so much is missing. LGBTQ avoids A (asexual). LGBTQ ignores I (intersex). LGBTQ precludes P (pansexual). LGBTQ averts another A (allies). LGBTQ quashes a second Q (queer or questioning — again, your pick).

But cram those together and create an even clunkier pile-up: LGBTQQIPAA. (Or concoct a mathematical amalgamation, and conjure this gargoyle: LGBT2QIP2A.)

“We don’t really have a terminology that does what we want it to do,” said Blount. “It gets in the way of what we want to say.”

Even LGBTQQIPAA (ten letters!) is hardly all-inclusive. Consider C, for cisgender. D, for demisexual. TS, Two-Spirit. Bigender, genderqueer, aromantic — just do a Google reconnaissance — and discover all the ways of slicing the spectrum.

“No matter how many letters you add to LGBTQ, it will never be the perfect term,” said Jared Odessky ’15CC.

Which is why another descriptor — long familiar, but reconstituted by a new generation — is an easily pronounced, eminently spellable one-syllable word.

“Queer,” said Odessky. “A much better umbrella term.” As one member of the Columbia Queer Alliance put it: “Queer is more encompassing.”

And not just at Columbia. Queer, as a new and improved synonym for the LGBTQ acronym, trends globally, though mostly among millennials.

Odessky confirms it’s an age thing: “Around my parents, I generally use gay, but among friends I tend to say queer.”

But Blount, a Columbia professor for thirty-one years, has issues there, too. “We should be very careful how we use queer,” he said.

The word’s jarring etymological narrative traces back to the early 1500s, when it denoted something strange, even eerie. By the late nineteenth century, queer became “a term of ridicule,” said Blount — a slur aimed at homosexual men. In the 1990s, gay activists politicized it (“we’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” was their prevailing mantra). About that same time, LGBTQ attained wide acceptance — and commenced to compete with queer for usage in both academia and pop culture.

“Queer is now a sign of pride, not derision,” said Odessky. “We’ve reclaimed a word that was used to harm the community.”

Reclamation is laudable, acknowledges Blount. “But by itself, queer is a weak umbrella,” he said. “It has been used so unevenly it can mean anything.” Plus the word’s pejorative history: “That, unfortunately, is lost on my students.” Picking between the two, Blount prefers the admittedly imperfect, but slightly more specific, LGBTQ.

“At least LGBTQ attempts to enunciate differences, rather than smoothing over them,” he said. “It doesn’t speak of identities in a single breath.” Then, he suggests: “The language is evolving, just as identities themselves are evolving. Let’s agree to disagree and put this aside.” Otherwise, get stalled in semantics — and the community won’t go forward. “I care about the language, but I care more about the movement,” he said.

Till then, though, the tiff over terminology remains “hotly debated” in Blount’s classes. “Language and identity cannot be separated, so students are passionate,” he said. And in this war of words, Blount rarely gets the last one. “I just try,” he said with a sigh, “to keep the peace.”