If you’ve ever glanced out the window of a plane flying into or out of LaGuardia Airport, you’ve seen Rikers Island. The flat strip of land, strikingly treeless, sits in the East River between Queens and the Bronx. With its clusters of long, low buildings, Rikers could be some sort of warehouse and distribution center, where tractor-trailers back up to bays to be loaded or unloaded. But there are no trucks. What is warehoused here is people — about 7,500 on any given day — detained by the New York City Department of Correction. Most of them, accused but not yet convicted of crimes, have been waiting months and even years for their day in court. Others have been found guilty and sentenced to a year or less in jail.

On a recent evening, Mia Ruyter, the education and outreach manager of Columbia’s Heyman Center for the Humanities, drives two graduate students — one of them a Columbia philosophy PhD candidate named Borhane Blili-Hamelin ’13GSAS — over the one long and narrow bridge that connects Rikers to anywhere.

Showing their passes at a checkpoint, the educators proceed to the Rose M. Singer Center, where women are held. After a lengthier ID check in the building’s foyer, they are ushered through a metal detector and a steel door, then a succession of five sliding iron gates, each clanging shut behind them, and finally one more steel door, into the Program Corridor, where they enter classroom 77.

A male corrections officer brings in eleven young women, aged eighteen to twenty-one. They are wearing identical khaki jumpsuits but manage to make individual fashion statements: a white kerchief around the neck, long pink sleeves, a Mohawk haircut. Quickly taking their seats on gray molded-plastic chairs around a battered folding table, they lean forward attentively, ready to spring into Socratic dialogue.

“Today, the topic is punishment,” announces Veronica Padilla, a PhD candidate at the New School and Blili-Hamelin’s teaching partner.

“What is punishment?” asks Bo, as the students call Blili-Hamelin — everyone’s on a first-name basis. “Let’s go around the room. Say one word you associate with punishment.”

“Something being taken away,” says one young woman. “Weapon,” says another. The rest respond in turn: “Jail ... Suffering ... Restriction ... Misery ... Depression ... Isolation ... Consequences ... Sadness.”

“What kind of punishment could involve pain?” Bo asks.

“Whipping by parents,” offers one student.

Another suggests, “Physical, mental, emotional punishment, by a parent or lover —”

“Or yourself,” interjects a third.

Discussing who has the authority to impose punishment, the class comes up with two groups: on the one hand, parents, lovers, and friends; on the other, the government, personified by corrections officers, the police, the DA, the judge.

“What differences are there between the two groups?” asks Padilla.

“You don’t have to listen to your family,” a student responds. “With the government, you have no choice.”

When the class takes a quick break, Blili-Hamelin, who has a particular interest in German idealism, the history of social philosophy, and metaethics, explains to a visitor that he’s not there to teach a lesson. “We’re not lecturing,” he says. “My goal is to get students to have as much of a feel for philosophical discussion as possible.”

His course, ReThink: Building Critical-Thinking Skills, is one of the ten four-to-six-week workshops that Columbia’s Justice-in-Education Initiative has delivered to a hundred young men and women at Rikers over the past year. The classes are taught mostly by Columbia graduate students and include subjects like computer coding, graphic design, architecture, and philosophical discussion. The goal, says Ruyter, who has led three graphic-design workshops herself, is to re-engage the students with education, help them develop skills that will be useful in finding a job, and encourage them to think about social-justice issues.

The Justice-in-Education Initiative is a partnership of the Heyman Center for the Humanities, led by Eileen Gillooly ’93GSAS, and the Center for Justice at Columbia, an interdisciplinary collaborative committed to helping to end mass incarceration through research, policy work, and, of course, education. The director of the Center for Justice is psychology professor Geraldine Downey, who has been involved in prison education since 1988, when, as a postdoc, she volunteered to teach at a facility in Michigan and saw how transformative education could be.

“Education is a pathway forward for everybody,” says Downey, “and society is better for it. Education benefits individuals impacted by incarceration, and that makes society safer. By allowing people who want to turn their lives around the opportunity to do so, we all profit.”

The Justice-in-Education Initiative began in 2015 with a one-million-dollar, three-year grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, part of what the Wall Street Journal called “a new push” from philanthropists and lawmakers to “prepare inmates for life beyond bars.” That same year, Columbia became the first US institution of higher learning to divest from private prisons. And in June 2016, the University signed the White House Fair Chance Higher Education Pledge, which commits colleges and universities to increase educational access to the seventy million Americans who have a criminal record — including those in prison.

“Opening up education to people who’ve been deprived of it reflects our values as an institution,” says Downey. “Columbia has made a big commitment to support people in getting a fair chance.”

In addition to Rikers, the initiative sends Columbia faculty to teach college-credit courses in three New York State prisons: Sing Sing, Taconic, and Bedford Hills, providing eleven courses to 130 students this year. The program also gives former prisoners a jump-start in continuing their studies with a skills-intensive four-credit humanities course, Humanities Texts, Critical Skills, offered on the Morningside campus through the Department of English and Comparative Literature.

At Taconic and Sing Sing, courses taught by Columbia faculty, along with the faculty of six other participating colleges and universities, are coordinated by the Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison, a nonprofit run largely by former prisoners. The Columbia-taught courses are good for Columbia credit, but there are not enough of them offered for students to earn a Columbia degree. So all Columbia credits earned by students in the Hudson Link program are applied to degrees awarded by Mercy College and Nyack College. Downey would like to establish a Columbia degree program and offer more courses, but it’s not easy: on the prison side alone, obtaining security clearance for a professor is, she says, “a challenge.”

But when educators do get in, the results can be eye-opening. At Rikers, Blili-Hamelin wants his students to think in new ways — to “take a step away from the question ‘What’s my view on this?’ and focus instead on ‘Why should someone hold the view I hold?’ By examining the reasons why they hold one view as opposed to another, people might change their perspective on the issue, and change their perspective on people who hold views different from theirs. That, to me, is the ideal outcome.”

Rikers student Bridget Francois agrees.

“I really like this class,” she says. “The best part is debating. You learn to look at a situation or a topic from a different point of view, not only your own point of view.”

Asked if she hopes to continue her education, Francois replies in her rapid-fire staccato fashion, “I’m twenty-one. I’m in twelfth grade. I’m in here finishing my high-school diploma. I’m still trying to figure out what I want to do. I’ve always wanted to study psychiatry, be a therapist, but I also like journalism, because I love to write. I’d love to study a lot of things. I plan on going to Columbia.”

You should not have run from me. I am the great Apollo! I am not some shepherd boy.

Aisha Elliott — or Elliott, A., 92G0185, as the patch sewn on her pocket would have it — declares in imperious tones her idea of what Apollo might have been thinking as he chased down Daphne, the terrified target of his rapacious desire. She and seven classmates, all clad in baggy, prison-issue dark-green shirts and pants — Elliott’s hot-pink sneakers look defiantly jaunty — are analyzing Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a Literature Humanities class led by Columbia professor Laura Ciolkowski ’88CC, who is associate director of Columbia’s Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality.

Outside, tall chainlink fences topped by coils of concertina wire hold the students inside the Taconic Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison forty miles north of New York City in Bedford Hills, New York. But though the students can’t get out, ideas have come in.

“When Aisha says, ‘I am Apollo,’ you’re seeing her deep engagement with Ovid’s text, actually entering into the character of Apollo to address his motivations, and to analyze the relationships in the poem as a whole,” Ciolkowski says. “There’s a kind of entitlement to his character. Why? And how does that connect to the larger social and aesthetic structures in which this character operates?”

Elliott had some thoughts on that. “At issue in Ovid’s Apollo and Daphne is the concept of power and the way in which it is used to take away a woman’s agency,” she wrote in her final paper for Ciolkowski’s class. “Like Apollo, Tereus was also a male in a prominent position of power who abused and violated women.”

“There was a lot of rape in the poems that we read,” Elliott says. “Why were they raped? Was it based on how they looked, what they said, the lack of power that women have when it comes to men in powerful positions — just really interesting stuff that I never had a conversation about, and I get it now.”

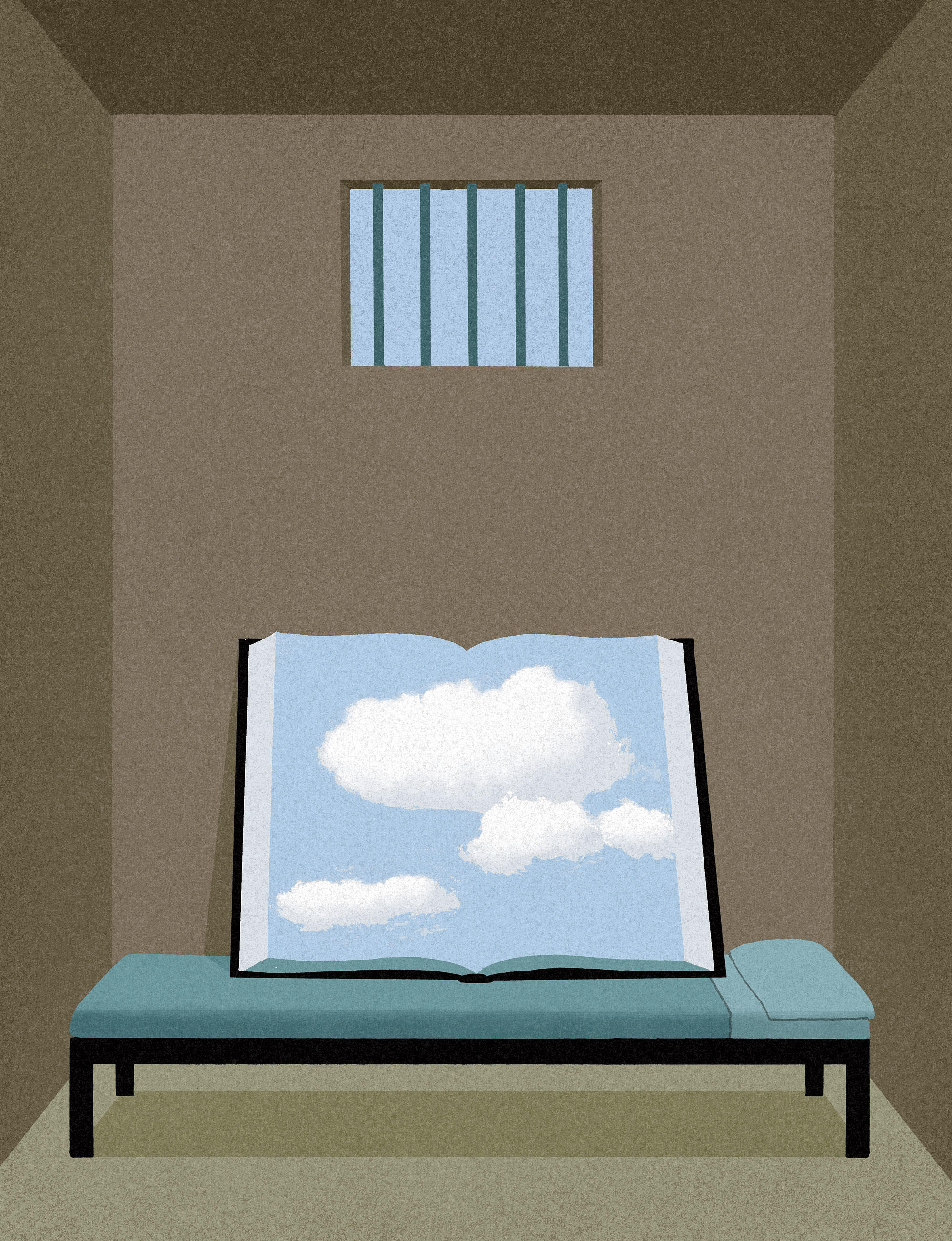

Her professor finds larger meaning in Elliott’s academic growth. “Prison is dehumanizing,” Ciolkowski says. “It’s objectifying, and the value of entering a classroom, a space in which you are a human being, not a prisoner, is absolutely incalculable. In some ways it’s also about futurity, the idea that one isn’t just one’s past. Outside of the classroom they are whatever it is that they did to get into that prison. Inside the classroom they are human beings with a future, with hope, with potential, with the ability to think outside themselves — ‘I am Apollo; I am not just myself. I am able to imaginatively enter into the worlds of others.’ That is immensely valuable for an individual whose space has shrunk down so dramatically, and whose humanity is largely taken away from her.”

The Justice-in-Education Initiative can trace its origins to the efforts of a handful of incarcerated women, including Elliott and her one-time fellow inmate Cheryl Wilkins, who is now senior director of education and programs at the Center for Justice.

The story begins in 1992, when Elliott went to prison, a twenty-year-old convicted of murder and sentenced to twenty-five years to life. “I’d dropped out of high school, and I started running the streets — carrying knives, carrying guns, selling drugs, just being an idiot,” Elliott recalls. One night, Elliott was out drinking in a bar in her hometown of Utica; she was underage, and another young woman ratted on her. As Elliott recounts it, “They threw me out of the club. I came out swinging. It just went straight downhill from there.” The other woman cut her with a razor — a large scar on Elliott’s forearm testifies to that. “And then I responded. My friend handed me a knife and I just went off.” She doesn’t deny her responsibility. “There were so many ways around that. But you don’t realize it until you stop thinking in a street-mentality way. When you educate yourself, you learn how to be human, how to be respectful, how to have morals, how to be nonviolent. You learn so many things when you’re going to school.”

Sent to the maximum-security Bedford Hills Correctional Facility (also in Bedford Hills, New York), Elliott set about earning her high-school-equivalency diploma, then dived into college courses in a program run by Mercy College. But in 1995, just as she drew within sight of graduation, President Bill Clinton signed anticrime legislation that cut off federal grants to prisoners for post-secondary education. State governments quickly followed suit. In 1994, an incarcerated person could earn a bachelor’s degree while doing time in the federal prison system or any of thirty-one state systems. A year later, practically all onsite college-education programs for prisoners in the US had vanished.

“That devastated me,” Elliott says. She and five other inmates — including Kathy Boudin, who was serving time for felony murder in the 1981 Brink’s robbery — formed a group that enlisted the support of the superintendent of the prison. Their goal was to bring higher education back inside Bedford Hills.

Two years later, in 1997, thirty-five-year-old Cheryl Wilkins arrived at Bedford Hills, sentenced to up to ten years for robbery. Wilkins was aware that there had been a change in prison after college classes ended. “There were more fights, more arguments, a little more hopelessness,” Wilkins says. “So I jumped on that bandwagon and became a part of this committee to bring back college.” With the superintendent’s help, the inmate activists met with representatives from colleges, religious leaders, philanthropists, and volunteers, pulling together enough resources to build a computer lab and academic library called the College-Bound Learning Center, which Wilkins and Elliott helped run.

By 1998, volunteer professors from nine colleges and universities were teaching college courses at Bedford Hills for credit toward degrees granted by Marymount Manhattan College. One of them was Columbia’s Geraldine Downey, who taught an abnormal-psychology class that Wilkins signed up for. Wilkins had a brother suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, and she wanted to learn more about it.

“Cheryl did her project on developing a booklet that provided information to families about schizophrenia,” Downey says. “This opened up something new for me to use in my classes. Students in prison — not necessarily because they’re in prison, but because they are older and have lived life longer — they’re asking, ‘Why does this matter? How can this be applied?’ It makes you think as an educator in a different way. You think, ‘Can I take these academic concepts out of the ivory tower and explain them in a way that the incarcerated students will find useful?’”

Wilkins was released in 2005 and immediately went to work for a nonprofit supporting the efforts of men and women with criminal records to pursue higher education. She was equally concerned about incarceration’s impact on children and families. In 2009, Wilkins, having added a master’s in urban affairs from Hunter College to the bachelor’s in sociology from Marymount Manhattan College that she’d earned in prison, joined with Boudin, who was released in 2003, to develop the Criminal Justice Initiative: Supporting Children, Families, and Communities, based in Columbia’s School of Social Work. Aimed at addressing the social repercussions of mass incarceration, that initiative — through the efforts of Wilkins, Boudin (who became an adjunct professor at the School of Social Work in 2013), Downey, and Columbia provost John Coatsworth — grew into the Center for Justice.

The United States has 5 percent of the world’s population but about 25 percent of its incarcerated people, with 2.2 million behind bars in prisons and jails. As the Center for Justice aims to reduce these numbers, education has proved a vital tool: according to Downey, who teaches at Sing Sing, “Being a college student in prison is the best-known protection against recidivism.”

Statistics compiled by Hudson Link bear her out: in New York State, 42 percent of men and women released from prison return within three years. Among those who have completed two semesters or more of college while incarcerated, the figure is 4 percent. And according to a 2013 Rand Corporation study, every dollar spent on inmate education translates to four to five dollars saved on re-incarceration. Yet political opposition to college education for prisoners remains implacable.

Even if education supports rehabilitation, opponents argue, imprisonment serves other important purposes as well — including deterrence and retribution for bad acts — and rewarding prisoners with free college courses arguably contravenes those goals. When New York governor Andrew Cuomo sought public funding in 2014 to support a small program of college education in a few New York prisons, legislators in Albany killed the plan.

“It should be ‘do the crime, do the time,’ not ‘do the crime, earn a degree,’” argued George D. Maziarz, a state senator from western New York. “It is simply beyond belief to give criminals a competitive edge in the job market over law-abiding New Yorkers who forgo college because of the high cost.”

Christia Mercer, who is the Gustave M. Berne Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Columbia, and who taught Introduction to Philosophy in the spring — her fourth course at Taconic Correctional Facility — finds the objections unpersuasive.

“The vast majority of people who are incarcerated are there because they were in circumstances that gave them very few options,” Mercer says. “Eighty-two percent of the women at prisons like Taconic experienced severe physical or sexual abuse as children; 75 percent suffered physical violence by an intimate partner during adulthood; and at least a third of them were raped at some point in their lives. They were in substandard schools that offered no counseling. And so, many of them self-medicated, and it was often in a state of self-medication that they made their mistakes — some of them did terrible things, which they now unblinkingly admit and deeply regret.

“What these women needed when they were arrested was not punishment. What they needed was a chance to rehabilitate themselves. So it’s not clear to me what the point of ‘prison as punishment’ is. But there is a point to rehabilitation.”

For Downey, the point extends to families and society at large. “Education allows people who have been impacted by incarceration to take leadership in reducing social problems,” she says. “Many people in prison are parents, and education gives them a way of connecting with their children and inspiring them to continue on the educational path. It makes them better parents. That’s what my students have said to me about education and families: that children recognize the value of what their parents have taken on.”

Still, prison is far from an ideal learning environment, Mercer observes. Incarcerated students use libraries with limited content, have no access to the Internet, and have to write papers in longhand.

These students can be a challenge in some surprising ways, Mercer has found. “I think the students at Columbia are very good at being learners and very good at reading what’s expected of them in class,” she says. “They’ve been trained their whole lives to be good students. My students at Taconic are often brilliant and insightful, but they have not been trained to be good students. I’ve discovered that if you pose a set of questions to a group of Columbia students and expect them to answer the questions, then that’s what they’ll do, because they’re dutiful students. But if you do that with the Taconic students, they might be prepared to ask very different questions, because those other questions are the ones most interesting to them.

“Then the discussion goes in a direction that I as a professor would not have set it in, but it turns out to open up a part of the text or nature of a character that I had never thought of.”

She cites her Taconic class’s take on Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: “In Twelfth Night, Maria plays a trick on Malvolio. Columbia students mostly think it’s justified, because Malvolio comes across as a pompous dude. My students at Taconic agreed that Malvolio is a bit of a jerk, but they thought that abusing him in the way that Maria did, and putting him in a situation to suffer in the way that he suffered, was not deserved, and that she and her friends took too much pleasure and delight in his suffering. The Taconic students opened up a moral element in the text that I had never seen before.”

For Mercer, one crucial thing about the Columbia program is that students are proud to be in it. “It gives them a sense of purpose,” she says, “and they work extremely hard to prove that they can do the kind of work that a Columbia student does.”

Aisha Elliott is one example. Mercer had her as a student in two of her courses. “The thing about Aisha is that she mentored women,” Mercer recalls. “A lot of the students in my class were in the college program because Aisha told them they had to be.”

“I didn’t feel like I was entitled to an education in prison,” Elliott says. “But I thought, ‘Now that I’m in prison, I’m going to take full advantage of everything that the state has to offer.’ Clearly my head was full of ignorance and street stuff. Once you get that out of your head, you need to fill it with something. Get rid of the streets, get rid of the ignorance, that stupid mentality that you had, and educate yourself. And I did. Prison is a horrible place. It’s the worst place in the world to be, and there were thousands of people there who should not have been there. But once you know how to write a paper, once you can have a conversation with your professor — there are so many things that education does for you.”

Downey has asked her incarcerated students what being in a college classroom says about them, about who they are.

“They told me it meant they were courageous, creative, committed knowledge-seekers, that they were determined to make something of themselves while doing their time,” Downey says. “It meant that they were resilient and able to lift themselves above the daily horror of life in prison. And they said our coming there as professors showed them that we believed in them — and that affirmed their belief in themselves.”

Last June, Elliott, locked up at twenty, was released from prison a forty-four-year-old woman (“an age I dreamed about for years,” she says). Her daughters were one and three when she went to prison. Elliott’s father was able to bring them to visit her once or twice a year; the girls grew up in the care of Elliott’s sister and their babysitter. Rakeisha, twenty-eight, is a licensed clinical social worker, and Aliya, twenty-six, is a health aide for disabled people and is studying radiology. They and their mother remain very close.

For the time being, Elliott is living in a reentry program in Queens, where she works in a thrift shop. She’s looking into the possibility of going to law school and adding a JD to the Marymount Manhattan College sociology degree that she earned behind bars. Says Ciolkowski, “I love that Aisha is moving on with her life. She’s a unique and incredible person, and I’m so honored to have known her.”

For Elliott, her classes taught her another lesson. “Education is not something to keep to yourself,” she says. “Like if we’re all poor and we get some food, you have to share it with the other poor people. I feel the same way about education. If you have it, you have to share it with people.”

Not a Number

Perhaps no faculty member in Columbia’s Justice-in-Education Initiative understands how much college courses mean to incarcerated people as well as Kirk James. That’s because he has been a student as well as a teacher in prison.

In 1994, at age eighteen, James, who had no prior offenses, was sentenced to seven years to life under the Rockefeller drug laws. At the time he was a community-college student in Queens, studying criminal justice and hoping to be a lawyer. One day, he was enticed by undercover police officers to obtain drugs and guns for them; he put them together with a seller and spent nine years behind bars as a result.

“I know what it feels like for guys to have a visit and see their loved ones leave,” says James, now an adjunct assistant professor in the School of Social Work. “I know what it feels like to maybe not have a collect call accepted. I know what it feels like to be out of touch with your family for years, to go to the parole board and be constantly judged on something that you did ten, twenty, thirty years ago.”

What enabled him to endure imprisonment, he explains, was “the ability to go beyond the walls. And what allowed me to do that was education.” He was able to get that education because in 1999 he happened to be transferred to the Wyoming Correctional Facility, in Wyoming County, New York, which had a privately funded college program. “This experience was transformational,” James recalls. “My number was 9486325. It felt the most oppressive to me, the idea that someone could see me as only this number. I had a psychology professor — he would have these classes where we could talk about anything. The idea that what we wanted to talk about was important, that our feelings mattered, was validating. There was a validation of who we were. My idea of success is the ability to start to see yourself beyond being a prisoner — the ability to see yourself beyond a number. That’s what education afforded me.”

Last fall, James traveled forty miles up the river to Ossining, in Westchester County, to teach a two-hour, fourteen-week course called Race, Trauma, and Oppression at the maximum-security Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

“It’s been one of the most humbling, rewarding experiences of my life,” he says, “being in a room where twenty-five men are speaking about trauma, about vulnerability, about how to cultivate positive relationships. The thing that’s so powerful, which struck me immediately, was their amazing level of attention, as well as their ability and willingness to be reflective, vulnerable, to speak truth to themselves. We had a conversation — I said there was a great debate now between prison reform and prison abolition. You had folks in the class who said, ‘No, we need prisons.’ And you had folks who said, ‘No, prisons are inherently oppressive and traumatic.’ And the folks who were for prison, some of them started to come around and say, ‘Maybe it’s not that we need prisons, but that we need mechanisms to address behaviors that are dangerous.’

“Their ability to think critically is phenomenal,” says James. “I think if anyone sat in that classroom for an hour, their idea of prisons and prisoners would be shattered.”