Late on the evening of November 2, when Congressman-elect and soon-to-be Speaker of the House John Boehner teared up during his election-night statement, it marked the conclusion of a long and improbable journey by Boehner’s Republican Party. The GOP, which had been all but irrelevant after successive defeats in national elections in 2006 and 2008, had now wrested the House of Representatives from the Democrats only two years after Barack Obama’s historic election.

It is easy to look at the big Republican victory and conclude that the American people had rapidly tired of President Obama’s progressive — or in the eyes of some critics, socialist — policies, and made a sharp turn to the right. Defenders of the president, on the other hand, argue that the president’s party often loses seats in midterm elections, and that in this regard, 2010 was not unusual at all.

The first explanation reflects an ahistorical understanding grounded more in ideological feeling than in empirical evidence. The second is not so much ahistorical as it is oblivious to the real data from the election, or the extent of the Republican victory.

So what happened, then?

Not surprisingly, the truth lies somewhere in between the two interpretations.

How bad was it?

The 2010 midterms represented a major defeat for President Obama ’83CC and his party, but one that differed only in degree, not in kind, from those suffered by many presidents during their first midterm elections, going back to Warren Harding. In the 44 midterm elections since 1922, every president, except for Franklin Roosevelt in 1934, John F. Kennedy in 1962, Ronald Reagan in 1982, and George W. Bush in 2002, saw his party lose seats in both houses of Congress two years after beginning his first term. In 1970, Richard Nixon’s Republican Party lost seats in the House but gained one Senate seat. However, the loss of 63 House seats and 6 Senate seats suffered by the Democrats last fall is one of the worst defeats in history. Only Democratic losses in 1938, 1946, and 1994, and Republican setbacks in 1922, 1930, and 1958, were of a comparable scale.

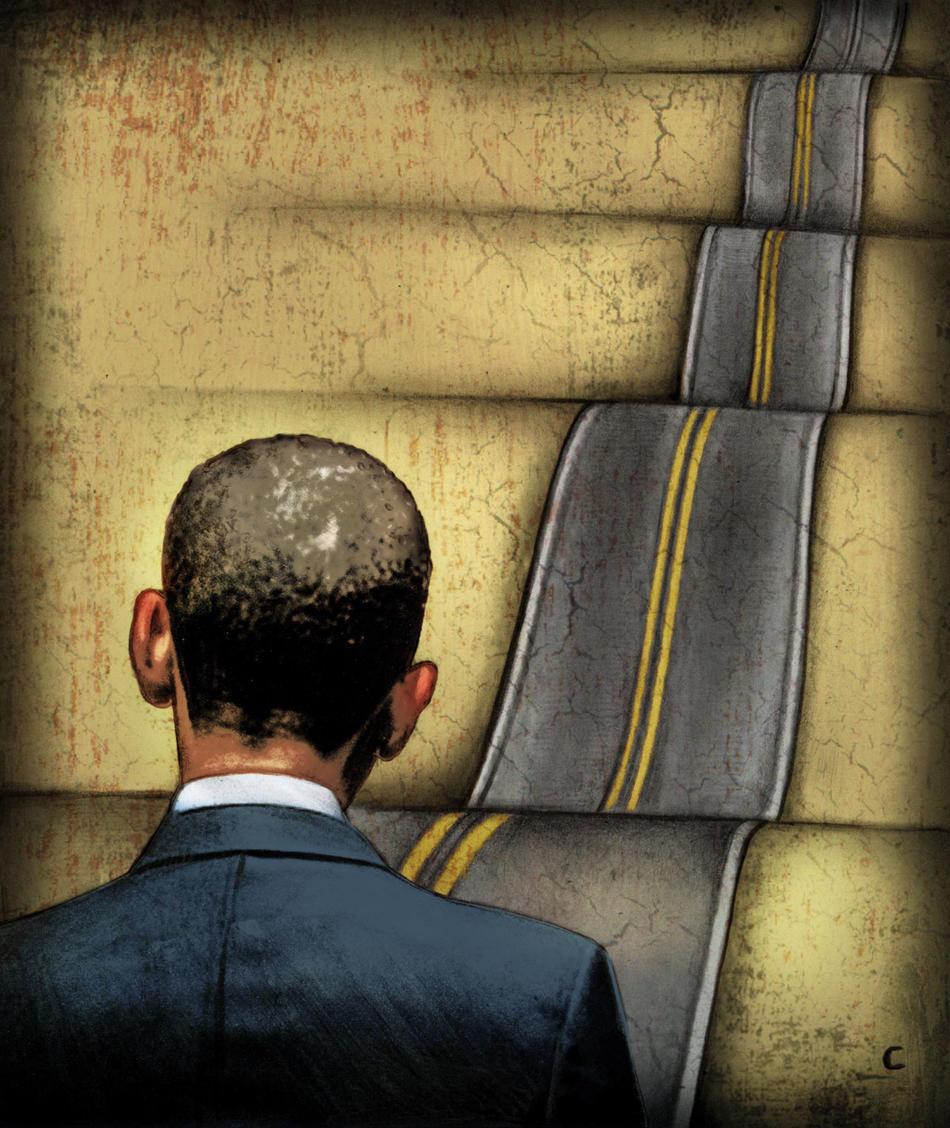

This background suggests that while voters were clearly dissatisfied with the president and his party, the notion that this election represented a significant swing of the ideological pendulum is inaccurate. A better explanation is that 2010, rather than standing in contrast to 2008, actually has a lot in common with the election that sent Barack Obama to the White House in the first place. Although 2008 was a political lifetime ago — when Obama could be said without irony to represent hope and change, the Republican Party was in free fall, and a tea party referred to a get-together involving a kettle and crumpets — many of the same political and economic conditions that framed the recent election framed the last national election as well.

The 2008 and 2010 elections occurred in a time of sharp economic crisis when voters were preoccupied with joblessness, sinking home values, and a bleak economic future. In both years, the country was involved in the unpopular wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, though by 2010 there was a timetable set for ending U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, and the war in Iraq had officially been declared over. For most voters these were distinctions without differences, since in both years the U.S. had hundreds of thousands of troops in these countries, with victory seemingly distant and an exit strategy equally remote.

In this light, the 2010 election begins to look different. Rather than an ideological shift, the Republican victory, like the Democratic landslide two years earlier, is the result of dissatisfied voters opposing the incumbent party. The same electorate that was so anxious for change in 2008 punished the Democrats a short two years later for failing to turn the country around quickly enough. While Democrats and the Obama administration sought to persuade the public of the difficulty of the problems facing the country and of the value of the work they had already done, voters were unmoved. For the second time in two years, they threw out the incumbents.

No room for reason

An enduring economic downturn can make life difficult for incumbent politicians, regardless of party. But this only partially explains the Republican victory, and it doesn’t explain why the Democrats lost so badly. While this loss was essentially unavoidable for the Democrats, it was probably possible to have limited the scope. The Republican Party campaign of 2010 was colorful, exciting, bizarre, or frightening, depending on your political views, but its impact was not unusual. The base was a little more mobilized than in most years, but extremist candidates in Delaware, Nevada, and elsewhere also cost the party a few seats.

The Democrats and the Obama White House, meanwhile, made two enormous mistakes that helped drive up the Republican margin of victory. The GOP, a defeated shell of a party in 2008, one that was associated with both the failures of the Bush administration and the economic collapse of that year, rebuilt itself largely through seizing on voter anger with the economy and government and channeling it toward partisan goals. This was done not by presenting alternative policies or a rational critique of the Obama administration, but by allowing the most extreme and sometimes downright wacky attacks on the Democrats to drive the Republicans’ message.

The charges of socialism (and its apparent counterpart, fascism) aimed at President Obama, the constant talk about how the Democrats were taking away people’s rights to own guns, make their own decisions about medical care, or run their own businesses — all dramatic overstatements at best — resonated with many voters. The Tea Party movement, which, despite endless speculation by the punditry about its origins, has never been anything other than a Republican Party faction, tapped into the populist, antibailout mood, while the mainstream media gave voice to far-out accusations aimed at the president: He was planning death panels; he was driven by an “anticolonial” mentality; he lied about his religion; he hated white people; and he probably wasn’t really American anyway. The Democrats’ initial response to these unfathomably strange assertions was to view them as fringe opinions and ignore them.

On some level, given just how absurd these accusations were, this approach made sense. However, by not pushing back, the Democratic Party made it possible for these charges to gain traction among voters. A constant media repetition of these claims made them seem less strange and more plausible to voters with each passing day.

The Obama administration seemed to assume, in spite of increasing evidence to the contrary, that politics could be based on reasonable debate, and that groundless rumor-mongering had no place in the national discussion. Yet the political environment during the first two years of Obama’s presidency showed otherwise. Political debate was replaced by name-calling; any allegation, no matter how baseless, ended up on Fox News and other outlets and Web sites; and epithets like Nazi, fascist, Stalinist, and communist, formerly the refuge of the most marginalized political factions, were more or less accepted as part of the political debate. Rand Paul, the Republican Senate candidate and now U.S. senator from Kentucky, for example, compared President Obama to Hitler apparently because they both came to power during economically bad times and were good public speakers.

While the president should not be expected to have to state that he is indeed a citizen, is not particularly concerned about anticolonial politics, and is neither a Nazi nor a communist, the Democratic Party blundered badly by letting these accusations go unrefuted. And the White House, by not saying enough while these accusations became more frequent, allowed them to be taken more seriously than they should have been. In short, the White House viewed these comments as nutty and assumed that most Americans would share this view.

They were fatally mistaken.

Out of touch?

The second error the White House made indicated a political blind spot that is surprising given how well the Obama team both communicated and understood the gestalt of the electorate during the 2008 campaign. Critics and supporters of the current president all recognize that Obama came into office at a difficult time. Whether he has done a good job since then and whether the problems were insurmountable in a two-year period can be argued, but for most voters this debate is moot.

Voters care far more about outcomes, particularly economic conditions, than they do about where blame should be assigned, or how hard a president is trying, or how obstructive either party is being. President Obama’s inability to turn the economy around in only two years should not have shocked anyone, but the failure of the administration to develop an appropriate narrative on the subject is puzzling.

As the election approached, communication from the White House, and the Democratic Party generally, seemed to move in two related directions: reiterating the extent of the mess that had been inherited from the previous administration, and seeking to gain credit for the successes of the Obama administration. But given the problems confronting ordinary Americans — widespread unemployment, a deflated housing market, and ongoing economic fear and uncertainty — these arguments sounded irrelevant and even insensitive.

Beyond that, the extent of Obama’s accomplishments is a matter of debate. The White House continues to describe the health-care reform bill, passed into law in March 2010, as a major, even historic, accomplishment, but the bill has been broadly criticized from the left and the right. More important, trumpeting a health-care reform bill at a time when an estimated 59 million Americans are without health insurance (the provisions that cover most Americans don’t kick in until 2014) is sufficiently tin-eared to border on insulting. Similarly, while many economists believe that the economic stimulus bill saved the financial system from complete collapse, the argument that things could be a lot worse, a seeming source of great pride in the White House, is cold comfort if you are unemployed or cannot pay your mortgage. This inability to gauge the sentiments of the American people was exemplified last year when the White House floated the term jobless recovery as a way of showing that they were turning the economy around. It is baffling that the White House did not see that this phrase, and the attitude it represented, was not going to be well received by an angry electorate.

Even as a candidate, Obama was vulnerable to charges of being out of touch and aloof. The White House communications strategy in the months leading up to the 2010 midterms hardly dispelled these perceptions. In times of severe economic problems, presidents who want to survive politically must either solve the crisis or demonstrate their empathy and concern for the people. Obama did neither.

Reading the tea leaves

The midterm election returns Washington to a divided government with one house of Congress controlled by the party that is not the president’s. This is not unusual, since a similar dynamic — at least one house falling to the opposition — was in place during the last two years of George W. Bush’s presidency, the last six years of Bill Clinton’s presidency, and the entire presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. The difference now is that the partisan rancor is stronger than ever. During the Reagan administration, the Democratic majorities included many Southern conservative Democrats, who frequently voted with the president. No comparable situation exists today. Additionally, with no clear end in sight to the country’s economic problems, and even less agreement about how to fix them, the incentive to work together and share the credit for accomplishments will be outweighed for both parties by the inducement to keep the partisan pressure strong and to blame the other party for the inevitable ongoing turmoil.

The biggest strategic danger for both parties lies in misinterpreting the election results. For the Republicans, this would mean viewing their win as a triumph of the radical right-wing ideology that came to dominate their party in 2010. If they aggressively seek to implement policies based on this ideology, their popularity will suffer, along with their party’s outlook in 2012. The Republican leadership needs to find a way to temper expectations and keep the more radical members of the new Congress from forcing the party to overplay its political hand.

The Democrats, and the White House, need to significantly recalibrate their message. President Obama must convince voters that he cares about their economic suffering — a tall order given both the failure of the White House to persuade voters of this previously and the continued Republican campaign against the president. But if the White House is able to make the case, the president can reinsert himself into the heart of the political process. If not, the Obama presidency will have substantially ended, regardless of who is sitting in the Oval Office.