In September 2013, something extraordinary happened in Paris: the Columbia Global Center in Paris and the Bibliotheque nationale de France joined together to convene a group of writers from around the world for public conversations about the effects of globalization on culture. It was a great success, with even the Louvre celebrating the event by saying, “Happily, we have the Americans to remind us that Paris is a great literary capital.”

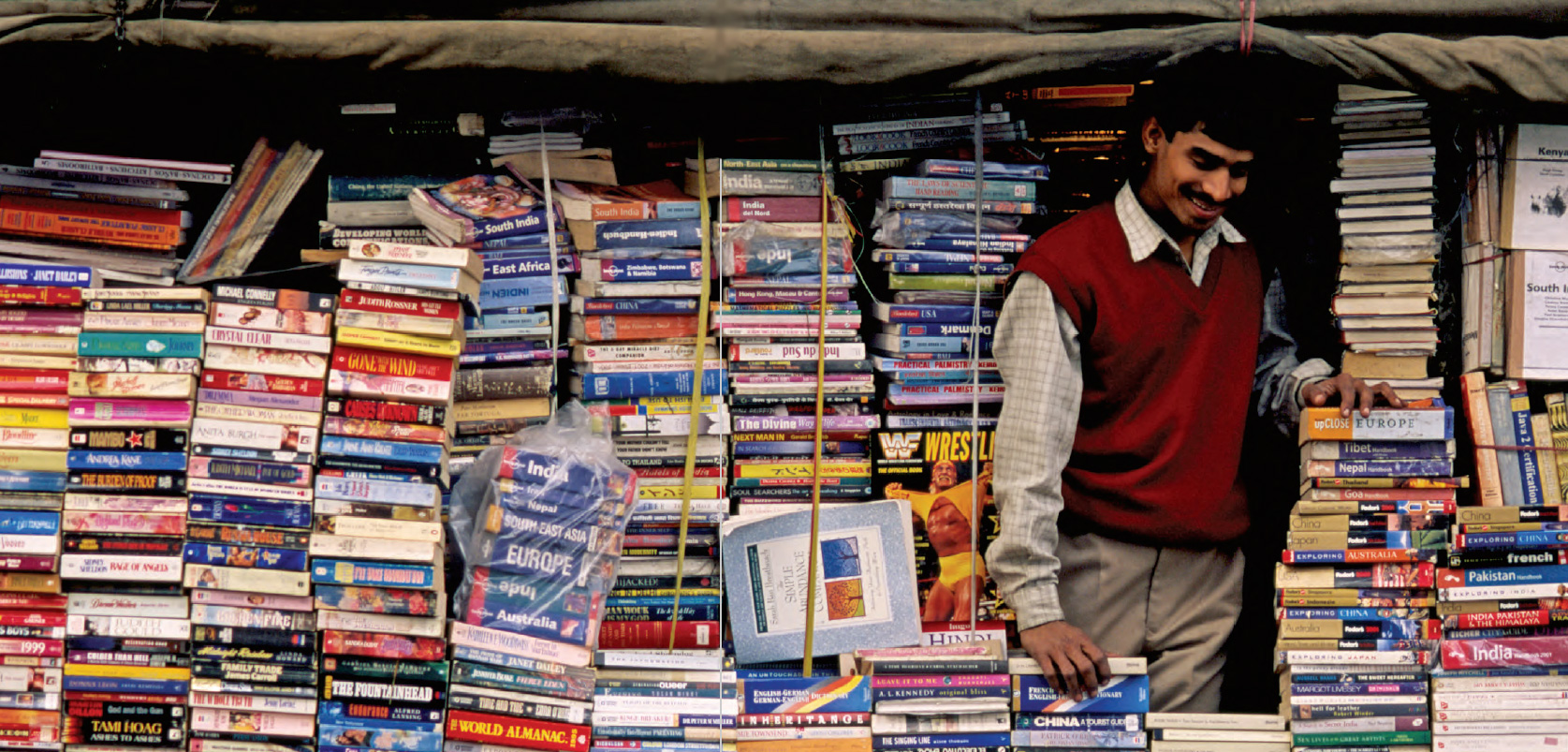

For the Columbia-BnF World Writers’ Festival’s second incarnation this past fall, again under the direction of Caro Llewellyn, we narrowed our focus to a specific region: India, a literary superpower whose writers have achieved immense artistic success in the Anglophone world, though have yet to gain the same kind of recognition across the European Union. For five days in September, fourteen Indian writers gathered with 2,500 members of the public for lectures, readings, and other events designed to encourage debate about the impact of our increasingly interconnected world on cultural production and consumption. In order to continue the conversation, we invited those writers to submit original essays, four of which are printed here.

— Paul LeClerc ’69GSAS,

Director of Columbia Global Centers / Europe

Indra Sinha

As a small boy, I had the good fortune to spend four years living near Lonavala in the Western Ghats, a range of jungle-covered mountains that run down the west coast of India.

It was 1957, and the road up into the hills wove in a series of steep hairpins past a small temple to Hanuman, the monkey god. Car wrecks were common milestones, and the truck drivers who ground up and down the road all day in first gear always left flowers as insurance. The garlands were promptly torn to bits and eaten by long-tailed langurs, who sat on the roof nibbling roses and marigolds, and watching the passing world with shrewd eyes.

When you reached the top, what a view. To the west was a forty-mile blur of coconut groves, tribal forests and swamplands, and a distant glint of salt marshes and creeks dotted with tiny shark-fin sails. Eastward, the escarpment rose still higher, with the mountains assuming fantastic shapes: vast rearing domes of rock wearing the sky like a wide blue hat. A basalt cliff jutting out three thousand feet was called Duke’s Nose, in memory of the Duke of Wellington’s famous snout. The last tiger in the area had been shot only fifteen years earlier by Mrs. Atkinson, a hunting, fishing Englishwoman.

In the jungles that covered the hills lived small men who hunted bandicoots and porcupines with bows. At night, leopards came down to take village dogs, and as I lay in bed, huge green moths with tails like teaspoons came flap-tapping at my window. Each morning I knocked my shoes on the floor to dislodge scorpions. When the rains came, the parched hills turned green in a night. A six-inch-high rainforest sprang up, roamed by red-and-black-striped centipedes whose fangs could split shoe leather. My five-year-old sister was bitten by a nine-inch specimen and nearly died.

It was a very particular place.

A few days ago, my wife reminded me of a short story I had written in the 1970s called “Gentleman, UK-Returned,” one of a group of tales set in the Paris advertising Lonavala of half a century ago. Reading it through again, I was struck by how much has changed. Today’s landscape is dotted with ugly villas and garish hotels. The hills where my friends and I roamed are mostly deforested, and the pockets that remain are full of tourists’ litter. The people in the story neither knew nor thought about much beyond their small world.

The big city, Bombay, was a far off, unreal place. England was still the heart of empire, and my Anglo-Indian friends (I mean the creole community as opposed to those English who had stayed on) continued to refer to it as home.

I dug out some more of my old stories. “Kallisto,” set on a Greek island in the mid-seventies, was essentially the complaint of an old lady whom my wife and I had met on the island of Poros. The war, the defining event of her life, was powerfully alive in her memory. Again, reading pages written nearly forty years ago, I sensed a particularity of place and sensibility that is now gone.

The early eighties found me sitting at a table under a plum tree in France, not far from the famous painted cave of Pech Merle. On the table was a typewriter and a glass of dark Cahors. In the typewriter was my first attempt at a story called “The Man in the Tomb.” I was smoking a Gitane, thinking — I’d been reading too much Lawrence Durrell — “Ah, this is what it is to be a writer.”

“The Man in the Tomb” was set mostly along a road from Galilee to Jerusalem. I had never been to Israel, but imagined a track lying like a white whiplash across limestone hills.

Six years ago, my wife and I visited Israel to research the novel of which my old story was the seed. We left Tel Aviv on an evening of filthy weather to drive to Galilee. As it grew dark, my wife, map reading, said, “We’re in the plain of Armageddon.” Armageddon, where a final cataclysmic battle will bring the world to an end.

The horizon ahead was silhouetted by a weird golden mist out of which emerged the two huge yellow arches of a McDonald’s.

I don’t like visiting Lonavala and the desecration of my childhood, but I was thrilled to read recently about a group of digital marketers who had gone there “to enjoy nature and fresh air.” One of them was in the garden of his hotel siphoning the scenery into his iPhone for future Facebooking when an enormous red-and-black-striped centipede rushed up and fastened its fangs in his calf.

O glorious invertebrate!

I never imagined I could feel such pure, intense joy as when I learned that Scolopendra hardwickei survives in my beloved hills, venomous and bad-tempered as ever.

Sudeep Sen

Over the past thirty years, writes my friend Olu Oguibe, a Nigerian-born American poet, painter, and academic, “globalization has left a signature imprint on architecture in poor and developing nations.” Structural security fixtures such as steel bars across doorways and windows have proliferated, he says, as have high walls, tall metal gates, and barbed or razor wire around businesses and residences. These fixtures have sprung up in response to a rise in crime that has followed spikes in unemployment, inflation, and cost of living brought on by the IMF and World Bank development-loan programs of the 1980s and 1990s.

In literature too, the impact of globalization has been mixed. One of the most obvious impacts has been in the area of mainstream multinational publishing and distribution, which is increasingly in the hands of very few houses — with various imprints and publishing arms fused and owned by a clutch of holding companies — who are increasingly the kingmakers of the literary scene. This has, in many cases, led to homogenization and a narrowing of publishing plans for the sake of profit. We all know there are various shades and kinds of hierarchies here: popular or genre fiction versus literary fiction, self-help and cookbooks versus serious non-fiction, with drama and poetry being the poor cousins.

The area of translation in world literature has suffered the most. Most contemporary non-English literatures (barring those of a few major world languages) hardly cross the linguistic boundaries within which they are written. Only after a major lifetime prize like the Nobel does a Jose Saramago or a Wislawa Szymborska get any global attention, translation, and there-fore wider readership. This is not how things would be in an ideal world; but the world, as we know, is not ideal or democratic or a level playing field. In this profit-driven environment, it is the smaller, local, “glocal” players that have the courage to experiment and encourage new writing, and still continue to publish experimental and cutting-edge writers.

On the other hand, by removing boundaries of geography, globalization has enhanced the flow of world literature — thereby enriching the literary world. Today it is not unusual to find Indian writers on European shelves and Afro-Caribbean writers on Indian shelves. Writers of merit now have the opportunity to access a world audience. And as writers, we have the opportunity to inhabit different landscapes without really being affected by access to the traditional literary cosmopolitan centers — I myself have lived for long periods of time in New York, and London, and also Dhaka and Delhi — and the literature that is being produced in these different places is creating subgenres of its own.

We also need to give credit to the liberation provided by one of the biggest drivers of globalization itself: the Internet. These are the days of high-speed broadband access to information — albeit mostly an overload of binary slush. Still, widespread Internet access has made literary reading, writing, and sharing more democratic. High-quality publications are now unlocked from the constraints of the print media. Of course, not everything out there makes the grade, but the floodgates are open, and that can only be good.

There will be arguments for and against globalization; our perceptions of its impact will change color and texture over time. What will remain unchanged, however, is the ability of literature and poetry to enrich, inspire, and create joy in the quietest, most passionate, and most intimate ways.

Sudeep Sen ’89JRN is a poet, translator, artist, documentary film director, and editor living in New Delhi and London. He has written, edited, and translated more than thirty books and chapbooks.

Salma

Tamil is among the oldest Indian languages. Poems and epics that are considered the zenith of traditional literature have been written in it. Tirukkural in particular can be celebrated as a scripture for the whole world for the way it presents a comprehensive code for living.

Globalization is a term that we hear often in third-world countries, particularly in countries like India that are home to such ancient traditions. But while people often complain about how globalization is transforming or destroying our culture, there is another side of the issue.

We cannot underestimate the alternative philosophies and literatures that globalization has brought to our doorstep. Ideas that were completely alien to traditional Indian thought have reached us through the doors it opened. Every writer can now read — at least in translation — about these ideas, creeds, and concepts — including feminism. These works have begun to influence our modes of creative writing, as well as our language, in the most natural way.

We had previously refused to think about matters that are a routine part of Indian and Tamil life, such as homosexual relationships and sex workers, or completely rejected them in the name of protecting our culture. Contemporary Tamil works that have appeared as a result of globalization now compel us to debate the living conditions of those who have been neglected or rejected.

During the nine-year period when I lived in my tiny, backward village in a state of exile from the outside world, it was only the information carried to me by globalization that helped me widen my perspective. Especially in a village that hid the very word “menstruation” and deemed it a shameful secret, these reading experiences created a language with which I could call attention to the violence perpetrated against women.

It was globalization that familiarized me and other Indian writers with concepts like structuralism, post-modernism, and deconstruction, and the writers who experimented with these concepts in their books, such as Orhan Pamuk, Sartre, Camus, and Foucault.

Countless contemporary writers are proving the truth that knowledge does not belong to individuals. An essay written in some corner of the world is uploaded to the Web, immediately kicking off a worldwide debate. Owing to the globalized relationship between writers and readers, the world is indeed becoming very small.

For me, globalization is a happy development. In my youth, when my beliefs were shaped by God and the rules of society, it was Karl Marx and Marxist philosophy that liberated me. Books like Dostoevsky’s White Nights and Other Stories and The Brothers Karamazov engendered a philosophical quest in me. The fighting spirit that I had imbibed from the great works of Russian literature and the poetry of great writers like Anna Akhmatova gave me the impetus to liberate myself from the demeaning existence that patriarchal society had ordained for women.

Reading Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Alexei Tolstoy’s The Ordeal made me experience the tragedy of wars that had been fought long ago as well as those being fought today. The philosophical quest that was instilled in me through works like Camus’s The Stranger and Sartre’s No Exit destroyed some of my illusions about life. The poems of Bertolt Brecht and Anna Akhmatova instilled a combative spirit in me, and Mayakovsky’s words significantly affected my poetic diction.

And Western ideas of feminism came to me through the works of Rosa Luxemburg, reinforcing my own.

How could all this be anything other than the serious impact of globalization on a writer?

Akhil Sharma

I have had a lucky life and been loved by many people: by blacks and whites, by Muslims, Jews, and Hindus. Once when I was having difficulties with my parents, a black woman told me about her brother whom she had not spoken to for many years, always thinking that things between them would eventually get fixed. He died suddenly, she said. Another time, because I feel bad about how little I earn, a friend who makes millions told me that he had started an affair with a woman who knew famous people, largely because he wanted to be near fame. For me, books offer the same responses to my deepest fears that close friends do.

Whether I am reading about Russians in the 1800s or a man hunting androids, books show me that I am not the only one who feels alone, who has feelings of uselessness, who has trouble controlling his emotions.

I believe that we are all the same, and that we have always been the same, and that we will always be the same. Because of this, the idea of globalization has always struck me as being like the sweet silly things that young people say to make their generation different from the generations that have come before.

I consume culture from around the world. In China a woman’s long fingers are described as scallions and in India they are described as flutes. But what does this matter compared to the desire that the writer has to celebrate the woman, or his love for the woman, and also indirectly himself by using attention-getting language?

I am not saying that I am unaffected by the fact that I consume culture from around the world. What I learn from works of other cultures, though, are either attitudes — Mo Yan’s cheerful satire against the state — or techniques. Tolstoy, for example, creates the effect of a godlike point of view by describing a character from the detached third person in one paragraph, switching to an internal point of view in the second paragraph, and switching to an external one in the third. The rapidity of this shuffle of perspectives discombobulates the reader. Attitudes are not original the way that technique is. Mo Yan is extraordinary, but he is not as delightful as Tolstoy.

The primary effect of globalization, aside from practical systems such as global supply chains, is to take information out of context and thus give our fears more justification. While before we were only afraid of the things that we brushed up against on the streets or maybe saw on TV, now with the Internet almost hooked directly into us, we feel that ISIS is two blocks away, and that any day now somebody on our street will have Ebola.

I am an example of globalization. I immigrated to America when I was eight, and I publish in French and Italian and Spanish. To me, though, the value of my work is not what it reveals about me, but what it reveals about you.