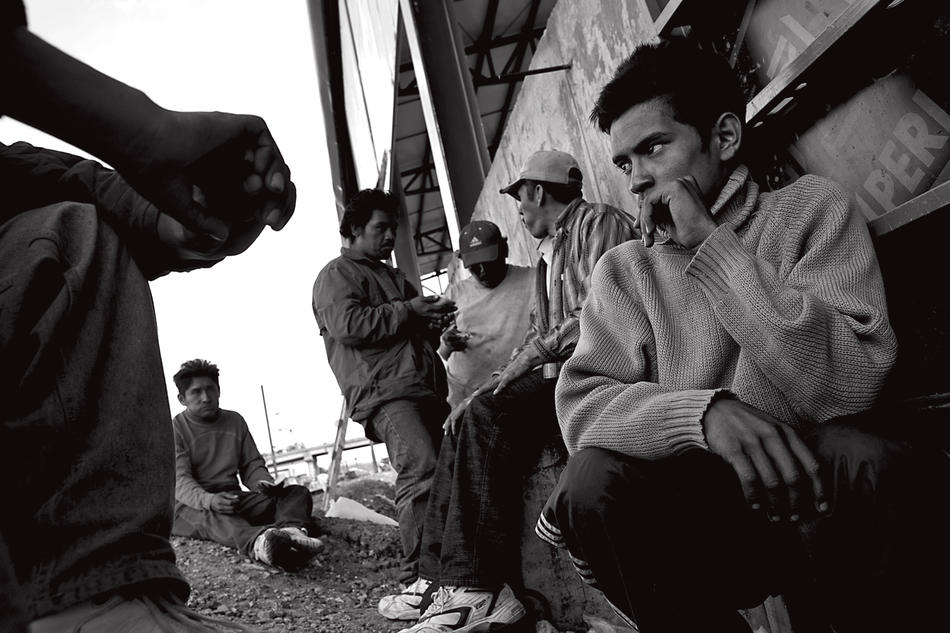

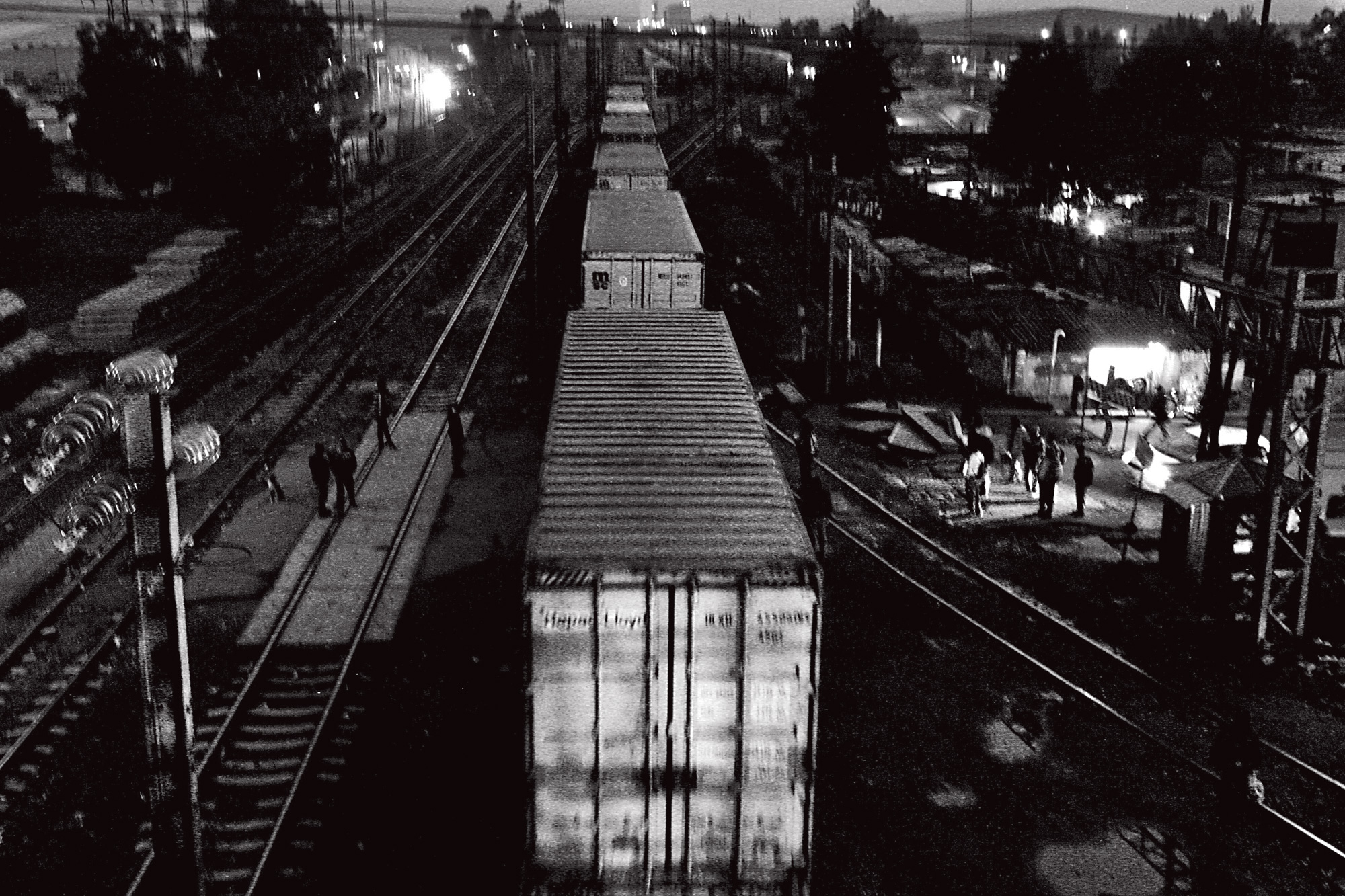

On an unseasonably cold summer night in the Lecheria rail yard, outside Mexico City, I sat under a bridge with a group of young people in their late teens and early twenties. Some tried to sleep, despite the deafening rumble of the trains as they passed. Others lay awake chatting, flirting, and keeping an eye out for robbers. Spirits were high. These young men and women were migrants from Central America, and they had just survived the worst of the perilous journey through Mexico.

When Americans imagine the treacherous paths of undocumented immigrants, they likely picture the Texas-Mexico border. Crossing the Rio Grande or the Sonoran Desert is indeed dangerous, and many people end up deported, imprisoned, or dead. But for thousands of undocumented Central American migrants each year, the US-Mexico border is merely the home stretch. The deadliest part of the journey starts at Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala.

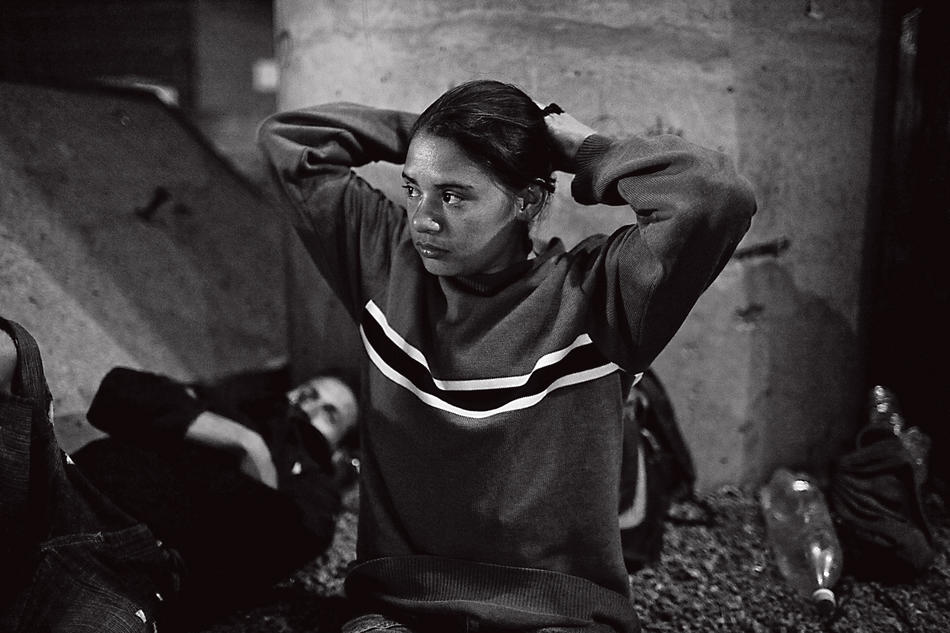

Migrants generally begin their journey on foot in the Mexican states of Chiapas or Tabasco. They continue aboard freight trains collectively known as la Bestia — the Beast — because of the hundreds who are maimed or killed each year falling from them or unsuccessfully climbing onto them. Along the way, migrants must pay off guides, thieves, gang members, immigration officials, railroad workers, and police. Because train schedules are unpredictable, they often spend days or weeks waiting in train yards, where they are prey to robbery, assault, and kidnapping. The risks are even higher for women: rape along the route is so widespread that many start taking birth control months before they embark.

My interest in migration as a humanitarian issue began when I was in college in Colorado. I majored in Latin American studies and worked with migrant activist organizations on the US-Mexico border. After college, while living in southern Mexico, I would see freight trains pass through town. They carried mostly timber, steel, and other building materials to the country’s northern industrial zones. Yet at least once a week, groups of young, dirty boys would appear in the town center, carrying nothing but small backpacks and plastic bags. They would buy water and food and use pay phones. They generally kept to themselves, although sometimes they would ask restaurants for their day-old tortillas. At night they slept under the trees that lined the periphery of the train yard. As soon as the next train came, they were gone.

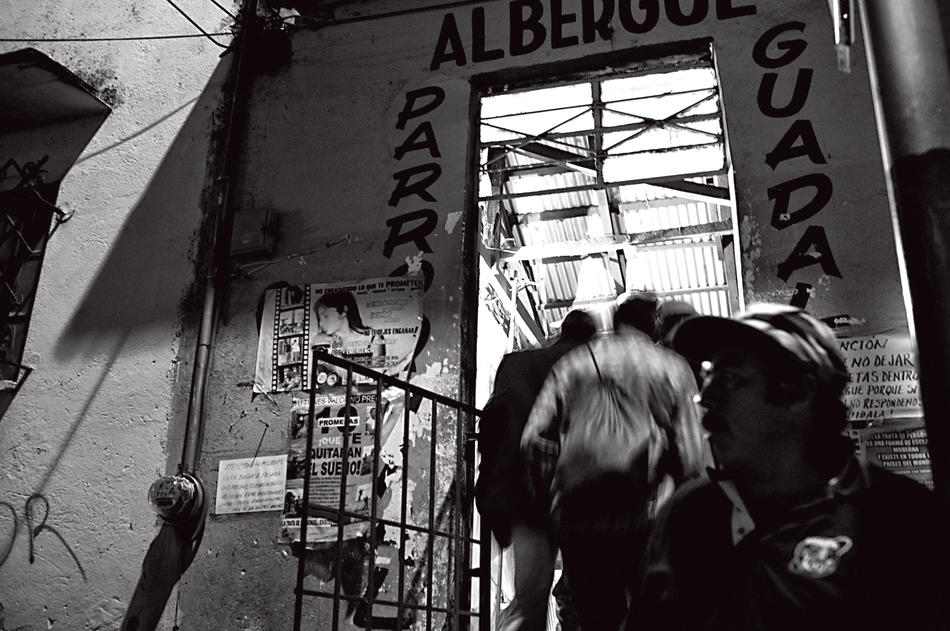

I wanted to learn their stories but was always warned off by the locals. Talking to them would be unsafe, I heard, but there was also a stigma attached to it. Some Mexicans saw all Central American migrants as delinquents, or even “Maras” — members of the infamous Salvadoran Mara Salvatrucha gang. It took me a long time to build up the courage to approach them. I wanted to do it right, not just take photos and leave. I would visit migration centers along the route, mostly set up by church groups so that migrants would have a place to shower and rest for a night. Sometimes I would talk to people at these shelters and follow them to the rail yards. Other times center workers or local journalists would accompany me there.

I could get scared. On a few occasions I left the rail yards immediately because of a bad look or an uneasy feeling.

But generally the migrants I met were kind and curious. Some didn’t want their photos taken, but most were happy to participate — to show Americans what they go through to make it to the other side. I worked to capture their feelings of hope and uncertainty, fear and anticipation. For me, the experience was as much about psychology as action.

Central American migrants are the most vulnerable community in all of Mexico, and the drug war has threatened them further: human trafficking has become a lucrative business, largely controlled, according to the Mexican government, by the notoriously brutal Zetas cartel. (I was fortunate to have taken these photos in 2008; a year or so later, to walk along some of the same tracks would have been a death sentence.) And while the drug war holds the attention of the news media, economic refugees from countries such as Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala continue to leave their homes and risk their lives in search of work.

Despite these hardships, many of the young people I met in the rail yards were brave and generous. They took care of one another. People shared food; they took turns keeping watch. They felt safe with one another, and I felt safe with them, too.