“Ginsberg came up to me once outside Butler Library and handed me a typed sheet with a sonnet,” John Rosenberg ’50CC told an audience of around 80 people in Low Library earlier this spring. “It was a very traditional English sonnet and didn’t yet sound like Allen Ginsberg, but I had the judgement to recognize that it was well done. And so Ginsberg appeared in one of the earlier Reviews during my editorship.”

Rosenberg, who is the William Peterfield Trent Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia, was part of an eight-member panel of past and current editors of Columbia Review, which claims to be the nation’s oldest college literary journal, having been founded in 1815. The gathering was organized by former Review editor Les Gottesman ’68CC, who got the idea after running into an old Review colleague, Alan Feldman ’66CC, at an MLA conference in California. Feldman suggested they have a reunion of Review staffers from the 1960s, and Gottesman expanded the idea to include those who came before and after. The result was a lively multigenerational assemblage of editors, writers, poets, scholars, and, especially, raconteurs.

“It was truly an astonishing constellation of gifted undergraduates, poets, and young critics,” Rosenberg said of the 1949–50 Review. In addition to Ginsberg, Rosenberg cited John Hollander, Richard Howard, and a teenage Norman Podhoretz, who, Rosenberg recalled, had the “chutzpah” to write a critical review of Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination. “We were a wonderful, nervy lot,” said Rosenberg, laughing. “I mean, we sort of thought that we invented the world.”

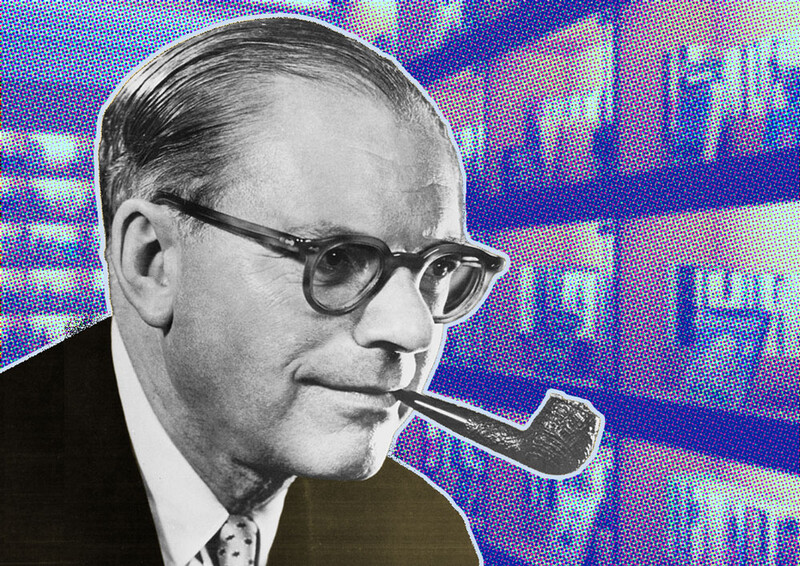

Novelist Hilton Obenzinger ’69CC, who edited the 1968–69 Review with Gottesman and Alan Senauke, joked that he hadn’t been back in Low Library since he and his friends occupied President Grayson Kirk’s office in 1968; National Review cofounder Ralph de Toledano ’38CC claimed he hadn’t been on the Columbia campus in 50 years, when Newsweek transferred him to Washington. Both men recalled editing Columbia Review during times of great literary ferment.

“Paul Auster would wander around in his long overcoat,” said Obenzinger, to a murmur of knowing chuckles, “clutching French poems and translations of Tristan Tzara.” Obenzinger also touched on the inspiration of Professor Kenneth Koch, and of the “exhilarating and nerve-racking” experience of being a classmate of David Shapiro, “already a major poet.”

The 90-year-old de Toledano counted Thomas Merton and Herman Wouk among his Review contemporaries and recalled the thrill of Senior Colloquium, headed by Lionel Trilling and Jacques Barzun: “When they began arguing with each other,” de Toledano said, “the sparks would fly.”

Norman Kelvin ’48CC, a World War II veteran and Distinguished Professor of English at the City University of New York, discussed the war’s anxiety-producing impact on the student body and paused to mention a fallen comrade and classmate, Marty Rosenberg (John’s brother), a navigator in a B-17 who was shot down in 1944.

“Those of us who were veterans and joined the Review were looked up to by those who were entering in ’46,” Kelvin went on. “But that passed very quickly, and rightly so. It was a life of the mind, it was talent, it was ambition to write that absolutely took over; and, in a curious way that people do not seem to remember, a kind of egalitarianism replaced this hero worship of veterans in just a matter of a few months.”

Author and essayist Phillip Lopate ’64CC related a controversy from the pre-Vietnam era of 1963, when free speech was the cause célèbre on college campuses: an entire issue of the Review was censored by the dean of student affairs over a poem containing the word shit. The magazine’s staff, which included Lopate, Ron Padgett, Mitchell Hall, Jonathan Cott, and Richard Tristman, quit in protest, though Lopate eventually rejoined what he called the “quisling” or “Vichy” Review, hoping to “change the system from within.” He was soon elected editor and went on to publish a 128-page Columbia Review, the largest ever.

The 1970s were evoked by writer Luc Sante (editor in 1974–75), who described the “confusion” and “void” of that decade (“We came to Columbia feeling that we had missed all the fun”), while Jennifer Glaser ’00CC referred to the “less glamorous” 1990s, during which the financially strapped Review staff resorted to such desperate moneymaking ploys as appearing as a paid audience on a short-lived TV show called Forgive or Forget.

The panel was rounded out by the Review’s current editor, Max Norton, who arrived at Columbia the year Kenneth Koch died and whose first memory of any campus poetry event was of going to Koch’s memorial service. Norton also introduced the latest Review, a reunion-inspired compilation of old and new pieces entitled “The Auld Lang Syne Issue,” which includes works by David Shapiro, John Hollander, David Lehman, Alan Feldman, Les Gottesman, and Norton himself, as well as a poem by Allen Ginsberg that appeared in a 1946 Review and was never republished.

When Norton finished his remarks, concluding the program, Ralph de Toledano spoke up. “May I interject?” he asked, and the crowd settled back down. “During my tenure Columbia Review was a very serious publication. But I would like to quote a limerick that we ran in one of the 1937 issues:

An erotic neurotic named Sid

Got his ego mixed up with his id.

His errant libido

Was like a torpedo

And that’s why he done what

he did!

And, thus, in a roomful of egos the wisest among them got the final word.