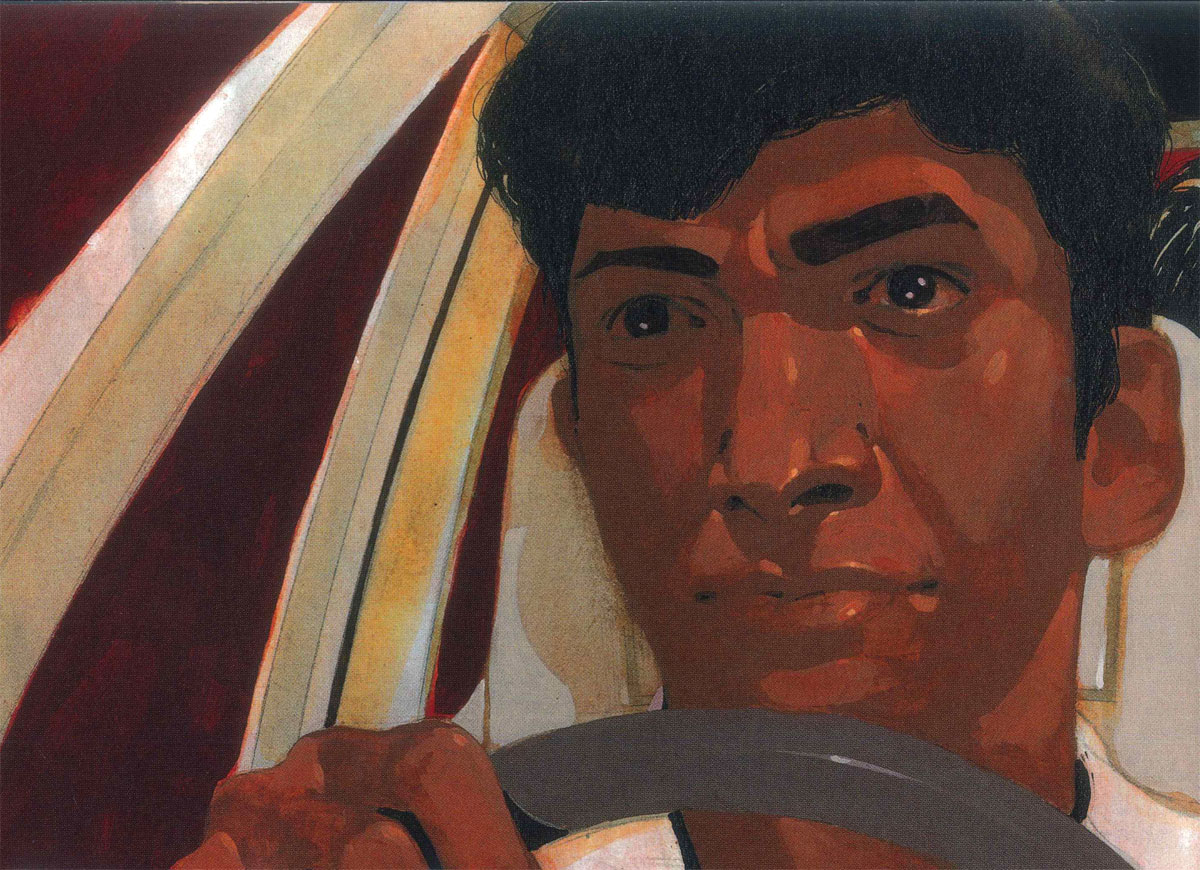

Two years ago, not long after quitting his job as a New Delhi correspondent for Time magazine, Aravind Adiga '97CC cleared his calendar and in about 40 days wrote The White Tiger — a radical revision of a novel he had abandoned the year before. He suspected he had "something special" on his hands, and with good reason. By January 2008 the book would be in print, and 10 months later it would receive England's largest and most prestigious literary award, the Man Booker Prize. Adiga, born in 1974, is the second-youngest winner in the prize's history (and, remarkably, the second Indian-born novice novelist with a Columbia degree to win it in three years — Kiran Desai '99SOA captured the 2006 Booker with The Inheritance of Loss). The White Tiger is the story of Balram Halwai, a young chauffeur from the bottom of India's social order who, through ambition, intelligence, unscrupulousness, and violence, masters the brutal world that made him. Adiga recently answered some questions about the book from his home in Mumbai, where he is working on his second novel.

I love your book's first sentence: "Neither you nor I speaks English, but there are some things that can be said only in English." But I think it prepared me for a more self-referential book than I found The White Tiger to be. Why did you decide to begin that way?

On the one hand, English is the primary language of many millions of more affluent Indians (like me); on the other hand, it's a language not spoken by most poorer Indians. They would love to speak English, too, but usually lack the financial means to learn the language. Nevertheless, a little English has crept into the speech of just about every Indian. So English is neither truly a language of poorer Indians, nor is it truly alien to them. Once I decided to write in English, and write about a member of the Indian underclass - in his own voice - I wanted to establish one thing right away: a narrator like the one I've chosen would not be speaking in English or thinking in English — but I, as a writer, assert that I can capture the range and flavor of his thoughts and ideas, the full texture of his personality, in my book. He will not be speaking in pidgin or broken or lower-class English; he will be speaking in a language with all the majesty and power that the spoken word has throughout India.

My sense is that many young writers of literary fiction go in fear of politics. But The White Tiger strikes me as a very political book. Were you motivated in part by a desire to raise awareness of poverty and corruption and social injustice in India?

I was motivated by the desire to capture a particular voice — the voice of the Indian underclass, which is perhaps 400 million strong, and which is largely invisible in Indian literature and cinema. Where they are represented, it's in stereotypical ways: as weak, ultrareligious, humorless figures who beg for the middle-class reader's pity and protection. I've noticed that a sense of humor and the capacity for vice are privileges accorded only to the middle class in literature and cinema from this country. I wanted to challenge that mode of representation of the poor — and of India (since India is still substantially made up of poorer people). The White Tiger isn't a polemic; it's a novel, told by a narrator with plenty of flaws. You are not asked to accept Balram Halwai's story, and indeed I believe there is internal evidence within the novel to challenge some of Balram's more extreme views on Indian society. But you are asked to hear his voice - the humor, insolence, agnosticism, cynical intelligence, and above all, his power to enter your middle-class world (even if, perhaps, you live in the U.S.A. or Europe or China) and disrupt it.

The book is full of memorable images — the president's house being blotted out by the smog cloud, the buffalo pulling the cart of buffalo skulls. Are these all things you've seen yourself? If so, did you immediately know that they belonged in this novel, or in a novel?

India is full of striking images — and not the clichéd ones you see in films that focus on spirituality and the Ganges. Life is vibrant, harsh, and poetic here. Everything in this novel comes out of my observations and notes. I knew that the images were too much for my work as a journalist — I was a correspondent for Time magazine — and that they belonged to another genre. In a sense, the images called for a novel to be written around them; and the novel followed like a suitcase in which to put these things, charged with political and poetic significance, that I'd seen.

How did Balram change as you wrote the novel, or did he?

The book was first written in the third person; and in the original ending, which owed a lot to Richard Wright's Native Son, Balram fled New Delhi after his crime and was caught by the police in a train station. I left the novel aside for a year, and then, in late 2006, rewrote it in the first person; and when Balram told his own story, and freed the story of the middle-class morality that had shackled it earlier, he changed the ending. In the new ending, the police become Balram's best buddies in Bangalore, which is exactly what would happen in real life. Obviously, Balram knows more about life in India than I do, and I'm glad he rewrote the ending.

How has the book been received in India?

The book sold well in India from the day of its release; and since the Booker, its sales have been astounding. My publishers in India expect to sell 100,000 copies or more of the novel, and these are exceptional numbers for the country. Not everyone likes it, obviously. I meant for this book to be controversial — it's a book that would work only if some of my middle-class readers got very upset by it. This has happened; while a majority of the reviews here have been positive, some have been very negative — and some hysterically so. One reviewer said she would prosecute me in court if she could. That's my favorite review of all: this shows me that the book is working. When a country like India has all the problems that it does — terrorism, a growing class divide, religious tension, poverty — one thing is for sure: any book that is published here to universal acclaim is, by definition, of little value. Either no one has read it, or no one was offended by it; in either case, the writer hasn't done his job, which is to get Indians to change the way they think about India.

Is winning a prize as big as the Booker somewhat awkward for a first-time novelist, because of the pressure it might put on you or on your second book?

Well, I live in Mumbai, which is probably the least literary big city on Earth. No one really cares here about the Booker Prize. Sixty percent of the people around me live in slums or on the pavement; and their concerns are how they will survive the days to come. I can never forget what's important in life, and what's important to me as a writer: to tell the stories of those whose stories are not being told.

Often, when reading a novel, I think of what a challenge a filmmaker would have in adapting it. But The White Tiger had, for me, a cinematic quality. Are there plans to make a movie of it? Is that something you'd like?

I've had a few offers; I pass them on to my agent. I wouldn't mind a film being made of this novel — more people will read the book, more will think about what Balram has to say, and with any luck a few will leave the cinema howling for my blood.