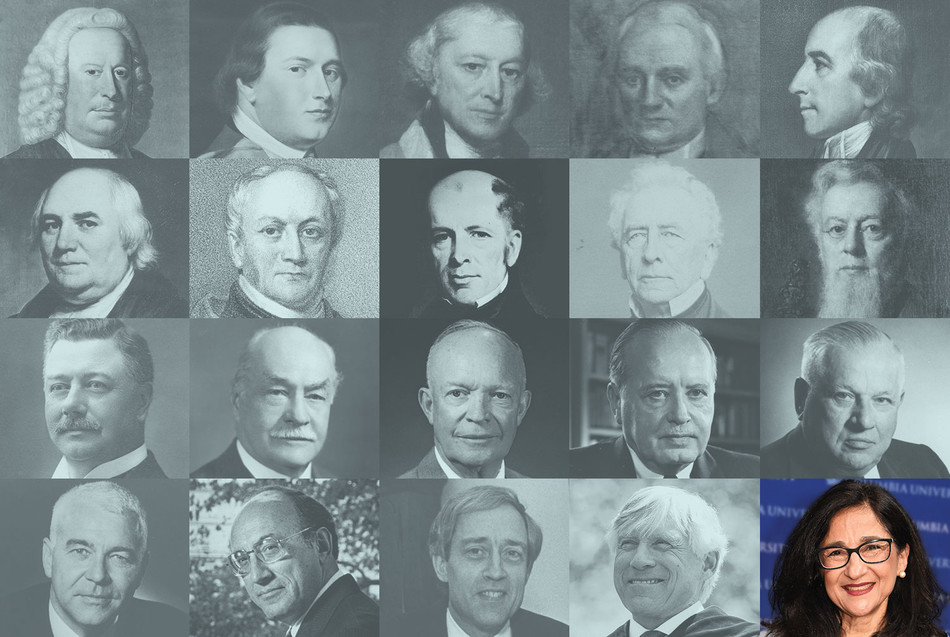

President Minouche Shafik, Columbia’s twentieth president, is the first new leader of the University since 2002, when Lee C. Bollinger ’71LAW, ’02HON succeeded George Rupp ’93HON. Back then, Barack Obama ’83CC was a state senator in Illinois, the Dow was under 11,000, and YouTube did not exist. As the years passed and the world saw vast social, technological, and political changes, Bollinger, the second-longest-serving president in Columbia history (Nicholas Murray Butler 1882CC, 1884GSAS led the University for forty-four years), was a constant; he is the only president that many Columbians have ever known. And so it’s natural that, with the arrival of President Shafik, Columbians should reflect on questions so basic that they are often taken for granted: What is the presidency? What are the president’s official powers and duties, and how are they to be carried out?

The answers lie in a 180-page document titled Charters and Statutes, which is Columbia’s primary administrative code. The charters, which established the institution and defined its rights, date to 1754, when King George II of Great Britain authorized the creation of King’s College in the New York colony. In 1784, after the American Revolution, a new charter from the New York State legislature renamed the school Columbia College, ended the requirement that the president be Anglican, and made Columbia a public, state-administered institution. But three years later, through the efforts of former King’s College student Alexander Hamilton 1788HON (a Columbia regent and one of New York’s representatives to the Constitutional Convention that year), the charter was amended, transferring all grants and property from the Governors of King’s College to a private board that called itself the Trustees of Columbia College in the City of New York.

The statutes, first set down by the Board of Governors in 1755, have grown in number and been amended frequently over the past 268 years (all amendments and new statutes require Trustee approval). They lay out the functions of the president, the Trustees, and the University Senate, which was formed in 1969 in the wake of the previous year’s campus upheaval. The official definition of the presidency can be found in the latest edition of the Charters and Statutes: “The President shall be the chief officer of the University and, subject to the Trustees, shall have general charge of the affairs of the University,” the document reads. “The President shall be the presiding officer of the University Senate and the chair of every Faculty and Administrative Board established by the Trustees. His or her concurrence shall be necessary to every act of a Faculty or of an Administrative Board, unless after his or her nonconcurrence, the act or resolution shall be again passed by a vote of two-thirds of the entire body at the same or at the next succeeding meeting thereof.”

As for presidential duties, four are noted explicitly: “(a) to exercise jurisdiction over all the affairs of the University; (b) to call special meetings of the University Senate and meetings of the several Faculties and Administrative Boards and to give such directions and to perform such acts as shall in his or her judgment promote the interests of the University, so that they do not contravene the Charter, the Statutes or the resolutions of the Trustees, or of the University Senate, or Faculties or Administrative Boards; (c) to report to the Trustees annually, and as occasion shall require, the condition and needs of the University; (d) to administer discipline in accordance with the Statutes of the University and the rules promulgated pursuant thereto.” (In practice, the Trustees — who, among many duties, select the president, oversee faculty and senior-administrative appointments, and manage the budget and the endowment — meet with the president multiple times per year.)

The Charters and Statutes are maintained by the Office of the Secretary, which was created in 1895 under President Seth Low 1870CC, 1914HON to support the work of the Trustees and facilitate governance of the University. Of course, no one back then, let alone in 1754, could have foreseen just how complex the institution would become. When King’s College first opened at the Trinity Church schoolhouse on Rector Street, there were eight students and one professor, the Anglican minister and philosopher Samuel Johnson, who was also president. Today, President Shafik, a prominent economist, leads a University covering four campuses (Morningside, Manhattanville, the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory) and seventeen schools (as well as four affiliate schools), with some 4,600 full-time faculty, 37,000 students, and 18,000 full-time staff.

For a job and an institution that expansive, an official set of regulations is indispensable. And while few Columbians have a copy on their nightstand, the Charters and Statutes are available to all on the Office of the Secretary website — a living document that has endured and evolved like the University it upholds.

This article appears in the Fall 2023 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "The Power and the Duty."