The moment that Edwin Justiniano heard the sounds in the flower bed alongside Butler Library, he flew into action: he set down the old computer he’d just unloaded from a cart on the brick walkway between Butler and Lerner Hall, hurried to the outdoor bulletin board a few feet away, and took out his phone.

Taped to the board was a flier with a phone number at the bottom. The flier told of a young family who, seeking safe passage, was threatened by drains and grates and cars. “The entire family will start making its way to water by foot,” it read. “Given our distance from a suitable body of water . . .” It was signed “Jennifer (wildlife rehabilitator).”

Justiniano knew the bulletin board well: as a Columbia groundskeeper, it was his job to prune it every day of its clutter. But there was one flier he’d made sure to leave up. He dialed the number.

It was seven thirty on a muggy July morning, and Justiniano, fifty-two, was working on Clean + Go Green, Columbia’s biannual recycling program (the other event is in December). The program, run by Facilities and the offices of Environmental Stewardship and Environmental Health and Safety, invites the community to drop off unwanted computers, furniture, electronics, and books at collection stations around campus.

The green shrubs rustled. A fuzzy little black-and-yellow bird waddled out onto the low stone ledge. Another followed. And another.

“Hello?” came a woman’s voice.

And another. And another.

“Jennifer?” Justiniano said, as Columbia’s duck population increased by a significant factor. “They’re leaving the nest!” Jennifer Chong ’98CC, a Butler Library help-desk consultant, was at home in Queens, eating breakfast. She knew from experience that the situation called for a trained hand. She rushed to the subway.

The ducklings, meanwhile, had toddled from the undergrowth onto the bordering stone ledge. Ana Goncalves, a Facilities cleaner, arrived with a flat piece of cardboard to keep the chicks — there were eight of them now, small and bumblebee-colored, moving around on the ledge like wind-up toys — from hopping off. One particularly bold duckling, rebuffed again and again by the cardboard, kept heading resolutely for the precipice. “She was the bad apple,” Justiniano said later. “She wanted to jump down and split.” Goncalves had a similar impression. “He was crazy — anything to get out of that place!”

Susan Hamson, University archivist and housemate to three cats, had been following the duck saga for days — she’d checked on the mother the night before — and had brought her freshly bleached pet carrier that morning. Hamson observed the antics of the renegade chick and saw a need for discipline. She picked the duckling up — so soft, so light! — and deposited it into the carrier. But the mother, whom Justiniano had seen for weeks hanging around campus fountains, stuck to her nest: one egg had failed to hatch, and she wasn’t ready to leave it.

To complicate matters, a crowd had formed. People on their way to recycling stations or taking campus tours stopped to have a look. While Goncalves tried to corral the ducklings into two boxes, Justiniano attempted to lure the mother duck from her nest by placing a chick close by. The mother peeped out, withdrew, peeped out some more, withdrew. Finally, she emerged, fretted her wings, lifted up in a ponderous arc, and landed on South Lawn. The chicks scattered again and, perhaps intending to follow Goncalves, leapt off the low wall and onto a brick surface less soft and wet than instinct might have led them to expect.

By the time Chong arrived, she later said, things were “a little chaotic.” A coworker retrieved a second pet carrier and a bird net that Chong had been keeping in her office in Butler. Someone else handed her a blue beach towel that she hoped to throw over the mother to immobilize her. Helen Bielak, who works in the Office of Environmental Stewardship, was strolling alongside Lerner when she saw “a trail of ducklings on the walkway, heading toward Journalism.” Bielak and Elorine Scott, a Butler security officer, helped gather the chicks and place them in the pet carrier that held their unruly sibling. But the mother was harder game. She flapped over the heads of her pursuers and landed behind them, rising and falling, wanting to stay near her young but avoid capture herself.

The frantic bird then fluttered to a recess in the Lerner exterior: a tight spot. Chong placed the duckling-filled pet carrier on the ground near the wall and set the other carrier beside it, door open. “The mother and ducklings were quacking at each other,” said Chong. “They were communicating. The mother couldn’t see the ducklings, but she heard them.” It was only when the other humans left and calm descended that Chong was able to drape the net over the bewildered creature, pick her up, and put her in the empty carrier.

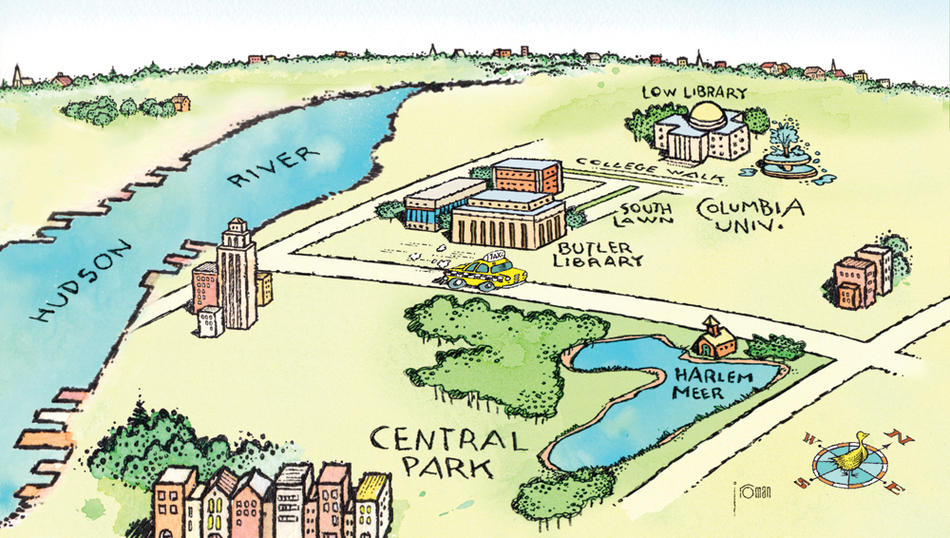

Chong grabbed the bird-stuffed cases, caught a cab, and chaperoned the family to the Harlem Meer, a pond at the northeast corner of Central Park. There, at the brim of the pond, Chong opened the ducklings’ cage.

The tiny birds, confused, huddled around their mother’s carrier. Chong picked them up one by one and plopped them into the water. They stayed near the edge, floating. Chong then released the mother, who glided right in. The babies formed a line behind their mother, and the whole party paddled toward the middle of the pond. Chong counted the chicks — there were seven. Seven? Chong saw with alarm that one of the ducklings had been left behind.

It was still at the pond’s edge, struggling to get back on land. Odd duck! Chong knew it would die without its mother, who was getting farther and farther away. As a New York State wildlife rehabilitator, Chong tended mostly to pigeons that were sick or injured or orphaned. She had also helped squirrels, sparrows, starlings, opossums, and gulls. But never had she done anything like this.

She went over to the duckling, scooped it up, cocked her arm, and hurled the young fowl as far as she could over the pond. Quaaaack. Plunk. Splash. The duckling, halfway between Chong and the mother, bobbed there in the water.

The mother heard the sounds. She turned and swam toward her straggler. Chong watched from the grass as mother and duckling reunited. “The mother touched her bill to bill,” she said.

Chong headed back to campus. She would be a little late for work.

Two days later, Justiniano was unloading more recycled computers by Lerner Hall in ninety-degree heat. These were the final hours of Clean + Go Green. Now, the program could count new life among the salvaged.

Justiniano, as he retold the story, walked over to the flower bed where the nest had been. He moved aside some leaves to reveal, in the undergrowth, delicate shards of white eggshells.

“It was a beautiful thing,” he said. “A beautiful thing.”