"It’s a year for death anniversaries,” says the Irish novelist Colm Tóibín in a lively, vowel-elongating brogue that perfectly serves his wit and at times seems to provoke it. “Shakespeare, James, and” — the voice purses into theatrical smallness — “our poor 1916 rebellion.”

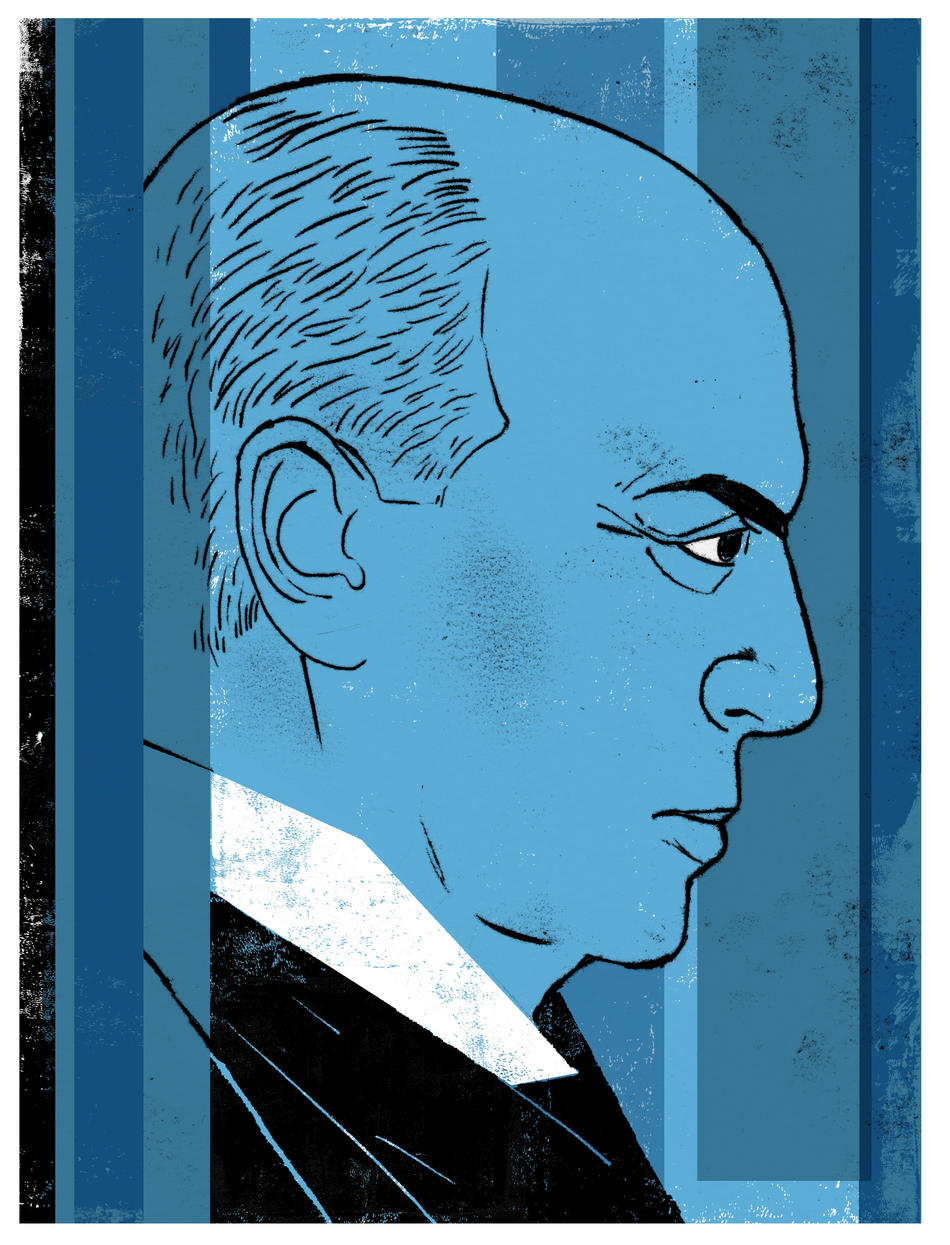

By James he means Henry James, the American-born, Irish-descended colossus of letters who died a hundred years ago in London, two months before the Easter Rising across the Irish Sea. It is James’s death that is foremost on Tóibín’s mind. Tóibín, a professor in Columbia’s Department of English and Comparative Literature and the author of the novel Brooklyn (the film version earned an Oscar nomination this year for best picture), teaches James, published a book of essays on him, and came out with a biographical novel, The Master, in 2004. Told from James’s perspective with heroic elegance, control, and insight, The Master captures James in the late 1890s, in the wake of his failed play Guy Domville and on the cusp of the creative outburst that produced the towering, “difficult” novels of his late period.

But what is James to us? What place does this most elaborate and indirect of writers hold in a time of shriveled attention spans? What can James, who was born in New York in 1843 and spent most of his life in Europe, offer to the modern reader?

As the editor and public intellectual Clifton Fadiman ’25CC wrote in a 1945 essay, James’s “‘rootlessness’ furnishes him with an international viewpoint and, indeed, an international style, both far more relevant to our own time than they were to James’s” — an observation that still vibrates in 2016. For Tóibín, however, relevance is measured in more immediate ways.

“If you look at the later novels, especially — The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove, The Golden Bowl — there is so much buried in them,” Tóibín says. These works of human conspiracy set among cosmopolites, heiresses, and literate provincials “are so filled with subtlety and nuance; there’s always a battle going on between what needs to be said clearly and what needs to be suggested. These texts are very open to interpretation and yield a great deal. To that extent, the books are supremely relevant.”

Tóibín points to two events that, in the late twentieth century, boosted the Master’s profile: the 1990 publication of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet, a foundational text of queer theory that illumines hidden gay themes in late-nineteenth-century literature; and the James family’s decision to gradually open the author’s archive at Harvard to more scholars, making available letters from James containing erotic hints that his executors had wished to keep hidden.

“People could now see James in a different light,” Tóibín says. “They began to see homosexuality as being an essential part of him, and this changed the experience of reading him. Within the academy, James moved from being this dead white male to this intriguing figure.”

Tóibín first read James in 1974, when, as a nineteen-year old at University College Dublin, he opened The Portrait of a Lady. He presumed that it was a novel of manners: Isabel Archer, alive with American spontaneity and rawness, was, in Europe, discovering a new style that impressed her. “I thought that would be enough for her — that she would replace an almost primitive style that she had gotten in Albany with a more cultivated style that she would find in Italy or, indeed, in a grand house in England,” Tóibín says. “And it was an enormous shock when I discovered, halfway through the book, that it wasn’t about style at all — that style was a way of concealing what was really going on in the book, which was a serious moral question about treachery.”

Portrait fascinated Tóibín, and he went on to consume the prodigious Jamesian banquet: some twenty novels, and more than a hundred stories and novellas.

“James’s best works are informed by the idea that there is a secret that, if known, would be explosive,” Tóibín says. “The secret in Portrait and the late novels is a sexual secret. James often takes his bearings from French farce. He’s trying to rescue that form’s major theme — adultery — from its own clichés by ennobling it with a Puritan imagination whereby he makes sexual treachery into something enormously and spiritually dark.”

But it was the later novels, in which James’s writing became increasingly dense and oblique, that held a special attraction for Tóibín. Of the prose in The Golden Bowl (1904), James’s last major novel, he says, “it’s as though the characters” — a wealthy American financier, his daughter, and their conniving spouses — “are operating as energy being released rather than as characters being portrayed. James is trying to deal, without being religious, with the idea of the soul or spirit as a sort of energy, and he needs a different style to register this.”

Being a Jamesian circa 1974–75 was a minor social hazard in the land of that other James — James Joyce. Tóibín’s friends were divided over Henry. “Some thought that the books mattered for their quality, their nuance, their style. Then others thought that the world of all these posh characters, who had inherited money and were living in permanent states of delicacy, really needed to be broken up.”

With the present spotlight on wealth inequality, one might expect James to have slipped entirely from favor. But for Tóibín, James’s attention to personal economic circumstances only enhances his currency.

“James is very good about what not having money does to people,” Tóibín says. “What will someone with no money do to get money?” This utterance kindles an idea that Tóibín pursues with the artist’s delight in invention: what if he team-taught a class on James with an economist?

“We could work with James to show what inherited wealth looks like in a society where not everyone inherits; where money skews relationships as much as it makes people immensely happy. We could show James being the great illustrator of this point. I’d call it ‘Trust-Fund Babies, Inherited Wealth, and the Late Novels of Henry James.’”