Six weeks before the October 2013 release of Carrie, Kim Peirce ’96SOA is locked in an editing room in Los Angeles. The air holds the dolorous last notes of blockbuster season and the first tingles of Oscar time, when studios trot out their prize ponies. The chief of the studio has been in and out. Phones ring, reporters wanting to know how the director of a gritty, personal, true-life film like Boys Don’t Cry came to remake an outlandish horror masterpiece.

Peirce gets it. She, too, loves the 1976 Carrie, directed by Hitchcock-goggled visionary Brian De Palma ’62CC. Calls it “brilliant.” De Palma is a friend, and gave his blessing. Peirce frames her movie not as a remake, but as a fresh retelling of the Stephen King tale, whose elements of an outsider, a knotty family life, a small town, bullying, and reprisal tugged a rope inside her.

Still, when the studio approached her in 2011, she was skeptical.

“I just didn’t trust it,” she says. “I thought, ‘Oh, it’s a remake. Hollywood is doing tons of remakes.’” Peirce has nothing against remakes — she loves, for instance, both the 1932 Scarface, directed by Howard Hawks, and De Palma’s 1983 Miami-splashed white-tuxedo edition. But in general, she felt that the studio system lacked the imagination and inspiration to do the process justice.

“I thought, ‘You guys want to do this because there’s money in it.’”

That motive at least made sense. Peirce had bigger questions.

The thing was this: she had made two movies, and neither seemed terribly relevant to Carrie. Boys Don’t Cry (1999), for which Hilary Swank won the Oscar for best actress, told the real-life story of Brandon Teena, a twenty-year-old transgendered person from Lincoln, Nebraska, who moves to a nearby town to live as a man. Brandon pursues Lana, a working girl; they fall in love. Brandon also befriends Lana’s pals, John and Tom, two roadhouse burnouts who take a shine to this sweet, slight, oddly appealing dude. When the men learn the truth about Brandon’s anatomy, they are enraged, humiliated; they beat Brandon, rape him, and, after Brandon files a police report against them, murder him.

Peirce’s second film, Stop-Loss (2008), was inspired by her brother’s military service, and expanded her study of violence and rural machismo. The story begins with an electrifying Tikrit street battle (shot in Morocco) before settling into a stateside fraternal drama about a group of returning soldiers, one of whom, Brandon King, after getting a hero’s welcome in his Texas town, is ordered back to Iraq. Believing this “stop-loss” policy unjust, Brandon makes the grim decision to go AWOL.

None of which sounded much like a pulp Gothic about a bullied schoolgirl with paranormal powers.

“Why do you want me to do it?” Peirce asked the executives.

Their answer surprised her. “Because of Boys Don’t Cry.”

Peirce was baffled. Then she read King’s book.

Peirce read Carrie three times during a trip to Turkey with her fiancée. King’s novel was a succulent little truffle. Reading about the lonely teenage misfit with a potent secret made a light bulb go pop! above Peirce’s head.

Though Carrie White and Brandon Teena could not be more different (Brandon: magnetic, bold, cunning, reckless; Carrie: shy, ungainly, sheltered, afraid), Peirce fell in love with the picked-on girl from Chamberlain, Maine. In Carrie she saw, as she’d seen in Brandon, a profound need for love and acceptance. The ache to be normal. To live.

Both characters possessed cryptic powers. Brandon could seduce girls with charms unknown to his rowdy male counterparts. Carrie could make objects move with her mind — a faculty that blooms with her late-onset menstruation. “With the period comes the power,” Peirce says. “That’s straight from King.”

In Boys, Brandon is unmasked in part by a tampon wrapper that he’d stashed under his bed. In King’s book, Carrie gets her initial period in the high-school shower (a scene made famous by De Palma’s slow-motion, soft-focus lyricism and Psycho-tinged tension), which rouses the other girls to taunt her and pelt her with tampons.

Both Brandon and Carrie are marked by blood and secrets. Both risk everything for a chance at happiness. Both attain a brief exaltation before their peers betray them.

“I do love a tragic structure,” says Peirce. “I love that everybody is culpable for the explosion that happens at the end. Everyone is part of the trigger point.”

“If you want to start at the beginning,” says Peirce, “you have to start with Carrie’s mother, Margaret, being terrified of this thing that comes out of her, feeling that she needs to kill it, then recognizing that it’s a baby, then falling in love with that baby and struggling with her terror and love all through their lives together.”

Here, Peirce nods to King’s book, which chronicles Carrie’s howling birth in Margaret’s bed: blood-sopped sheets, a butcher knife, a sliced umbilical cord, and a baby at the breast — a scene that did not appear in De Palma’s film.

“Each character is pursuing her primal need,” says Peirce. “Margaret’s is to protect her child; Carrie’s is to get love and acceptance and find a way to be normal. How wonderful that they both have such strong, conflicting needs, and that’s what fuels the movie from beginning to end.”

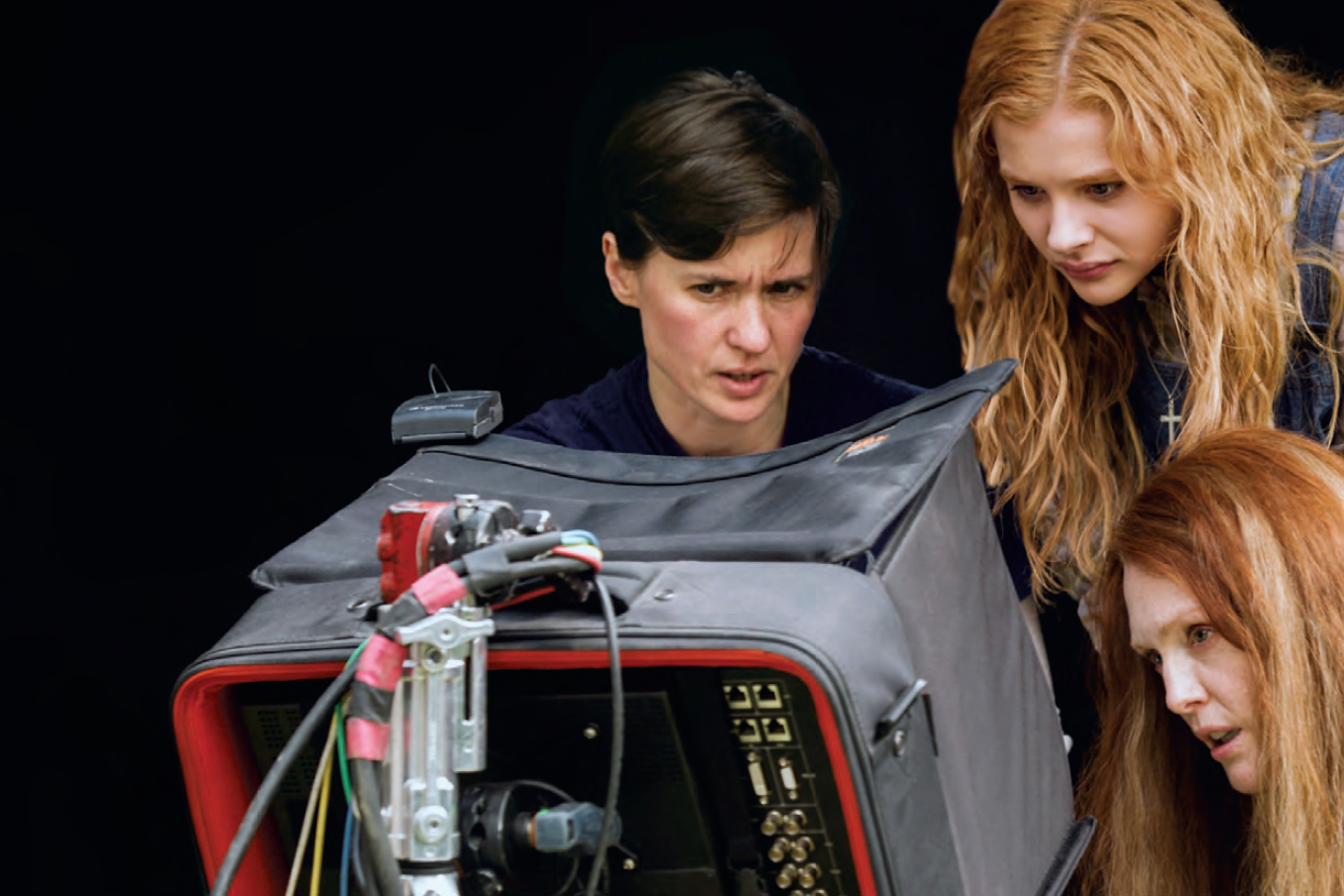

Sixteen-year-old Chloë Grace Moretz stars in the title role, with Julianne Moore as the religiously incandescent Margaret. In Moretz, Peirce had a Beverly Hills-raised, full-lipped, precociously poised actress endowed with movie-star je ne sais quoi (“If you have that quality, the camera just falls in love with you,” says Peirce. “You watch her face, watch an emotion play off it — she doesn’t have to do anything”), a child star who had worked with Martin Scorsese and Tim Burton, and whose un-Carrie-ish confidence Peirce sought to break down.

“We have to create for you a space where you don’t have all the things you’ve had since you were five,” Peirce told the teenager. “Success, money, confidence, love, support. Carrie doesn’t have these things. We have to transform you as a character from an overconfident child to a broken young woman.”

To that end, Peirce took Moretz to homeless shelters.

“That was sensitive. I didn’t want to use people who are less fortunate than us,” Peirce says. “So I suggested to Chloë that she owed it to herself, and to others, to see beyond how we live. She was open. She was wonderful. We went to shelters and worked with some girls and women who were very generous and talked to us about their difficult times. I said to Chloë, ‘Try to go beyond just listening and feel.’”

For three months they focused on getting Moretz to internalize adversity and rebellion. When Moretz finally teamed up on the set with Moore (“who is a master,” says Peirce, “she just is”), the director witnessed the fulfillment of that work. “In the relationship with Julianne, and under Julianne’s tutelage, I saw Chloë grow as an actor.”

Moore, a four-time Oscar nominee, had her own concerns.

“Julianne was worried that people wouldn’t love her character,” Peirce says. “And I said, ‘What do you mean? Margaret’s great. Everyone’s going to love Margaret.’

“We worked through Julianne loving this complicated woman through her love for Carrie. Margaret and Carrie’s love for one another is at the center of this movie. Yet there’s a tragic inevitability, because Margaret fears that the child is evil, fears that her powers could come out. Margaret is in a moral struggle: she feels she must kill Carrie, but she loves Carrie. So what should she do?”

Peirce, versed in Aristotle’s Poetics (core undergrad reading at the University of Chicago) and the lessons of her film-school teachers, is a demon for dramatic conflict.

“Carrie is bullied at school, bullied at home. She discovers she has a secret power, which maybe could make her happy, make her normal. So she explores it. When her mother finds out, she tells Carrie it’s the devil’s work. She tries to stop the power. But Carrie is desperate to have something of her own, desperate to be a whole person. She’s trying to be everything she’s ever wanted to be. ‘I can have powers and I can go to prom. I can be normal.’

“But we all know that she can’t.”

“Because it’s a Kimberly Peirce film, the horror builds from the truth in the acting and the relationships,” says Lee Percy, Carrie’s editor. Originally trained as an actor at Juilliard, Percy has edited more than forty features, including three with Oscar-winning performances: William Hurt in Kiss of the Spider Woman, Jeremy Irons in Reversal of Fortune, and Hilary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry.

For Percy, the heart of the film is the mother-daughter bond.

“I think Kim would say it’s the love story,” he says. “The relationship between Carrie and Margaret in Kim’s film is much more emotional, much more linked, much more aware of what holds them together than in the De Palma film, which is a great classic. Brian has his areas of expertise, and Kim has hers.”

Peirce was born in 1967 in working-class Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Her mother was fifteen. Her father was seventeen. Peirce remembers her parents as “larger than life” — her mother beautiful, alluring, adventurous, her father a charismatic hell-raiser brought up to “fuck, drink, and fight.” It wasn’t long before they each blew town.

Her father, a builder, went to Florida. Her mother went to New York. Peirce bounced around among relatives, lost herself in Saturday-morning cartoons. Got ahold of a tape recorder, too.

At five, she moved to New York to live with her mother, who had gotten a job as a waitress at the Plaza Hotel.

That arrangement didn’t last long. Peirce went to live with her father in Miami.

Her father started his own contracting business. In the late 1970s Miami began receiving mind-blowing injections of Medellín-cartel drug money. Construction cranes shot up like weeds.

Her mother sojourned in Europe, lived with sheikhs in Morocco. Both parents drifted in the patchouli of me-decade immoderation.

In Florida, Peirce learned to fish, swim, scuba-dive, play tennis. She was a sparky tomboy who read DC Comics and sci-fi–fantasy books like A Wrinkle in Time, who loved to draw and make animations with her Super 8 camera.

At times, her father became abusive. He’d been beaten as a kid, toughened up the Harrisburg way, and he repeated that pattern with Peirce.

His life moved fast. Money. Women. What Peirce didn’t know was that he was running cocaine in and out of the Bahamas on seaplanes.

When Peirce was ten, her mother returned from overseas and landed in Puerto Rico. Peirce went to live with her for a year.

She would ask her mother questions. Where did you live? What were you doing? How did you make money? Who were you screwing? Why did you come back to get me? What do you want? She wanted chronology, wanted to understand the mechanics of how one thing led to the next.

Her mother also brought into Peirce’s life a “complicated stepfather.” That situation, Peirce says, informed a lot of the physical and sexual abuse in Boys Don’t Cry.

Someday, when the time is right, she says, she will tell her own story in film. Until then, she will tell it through others.

Before Carrie, before Brandon, there was Pauline.

“I was wildly in love with this story,” says Peirce, who burns for her characters with the passion of a raptured mother. She doesn’t just love them; she is in love with them.

Pauline Cushman, an actress born in 1833 in New Orleans, was one-eighth African-American, a fact she concealed as a matter of survival. During the Civil War, Cushman became a Union spy, posing as a white Southern man in order to get her hands on Confederate battle plans.

It was a hell of a story, and Peirce wanted it to be her thesis project. She’d been drawn to Columbia’s film school for its emphasis on storytelling. Columbia meant “you’re going to write, write, write, and you’re going to take acting classes and acting classes and acting classes.” Peirce took three years of acting with theater director Lenore DeKoven and actress Carlin Glynn. “I loved it,” she says. “I wasn’t any good at acting, but I was good at the class, at reading the texts and understanding what the actors were going through and what they needed from me. I was glad the program made me write, work with actors, and use other media in addition to film, because it allowed me to create more work, make more mistakes, and learn more.”

Her first year, in 1992, the students shot video. Peirce knew from having recorded her family in different media that format wasn’t the crucial thing. And yet. Video.

“Look, we all bitched about it,” she says. “We were running around the Upper West Side in the horrible New York City heat with these ridiculously huge video cameras. We had all chosen Columbia and were like, ‘Aah, this is fucking awful, these cameras suck.’ We’d shoot these crazy videos, then go back to these old, bulky editing machines that had something called ‘timecode’ that none of us could figure out. You’d be up till six in the morning doing linear editing, you’d have your whole project edited, and then you’d suddenly ‘break the code’ and lose the whole thing, and then it’s time for class, and you’d say, ‘It was great, and it’s gone.’ It was crazy.

“But it became so clear to me — and this is said with a great love for film — that it was just about getting story down. I saw that no matter how technically weak the visuals were, whether they were done on Super 8, Hi8, PixelVision, or whatever, if the story was good, it worked.”

Peirce took the Pauline Cushman story to her writing teacher, playwright Corinne Jacker.

Jacker thought about it, and said, “I think you have a problem.”

“What is it?” said Peirce.

“Cushman dresses as a man to get a job,” Jacker said. “I think you want to write about somebody who dresses as a man because that’s who that person is.”

The insight sank in. Jacker was saying that the story wasn’t going to work as a movie because Cushman’s motivation wasn’t coming from an internal enough place.

That laid Peirce low. She had no story now. No thesis film.

At the time, Peirce lived in “the lesbian ghetto” of Manhattan’s East Village, home to artists, anarchists, squatters, drug dealers, academics, activists — “an oasis of queerness that was wildly more interesting to me than the straight white male world uptown.” For money, she worked nights at a Midtown law firm.

One evening, Peirce was at the law office.

During a coffee break, a co-worker, Hoang Duong ’94SOA, came over to her.

“Hey,” Duong said. “You should read this.” He handed her the Village Voice.

It was an article by Donna Minkowitz about the case of a young Nebraskan woman named Teena Brandon, who transposed her name, passed as a male, and won the hearts of the prettiest girls in the town. The story of Brandon’s life and death, told from a butch-lesbian perspective, jolted Peirce.

“From the moment I read that article, that was it,” she says. “Brandon was my child.”

“This is a girl with superpowers. She can stamp her foot and create a fissure in the earth. She can lift up a car. She can levitate the furniture.”

Peirce, in postproduction, is talking about Carrie while exercising her own earth-shaking power. With big-budget digital technology at her disposal, Peirce can summon not just the minor mischief caused by Carrie’s capricious flexing of her telekinetic muscles (if there’s a girl-appropriate superpower, Peirce has said, it’s telekinesis: emotions turned physical), but the massive destruction of the town caused by the full discharge of her adolescent rage. (De Palma, filming in 1976, had confined the ruined prom queen’s climactic vengeance mainly to the school gymnasium.)

“It was a blast to figure out how to use visual effects to better tell the story,” says Peirce. “As a writer, not only was I able to write on the page, write with the actors, and write on set, but now I could write throughout post, as I refined the action and the story with the visual effects. The question is always: who is Carrie, what does she want, and how would she use her power?”

With the Pauline Cushman story on the shelf, Peirce fixated on her new obsession. “I was in love with Brandon,” she says. “It was amazing to me that this female-bodied person lived as a boy, loved other women, and had the audacity to live like that, especially in the Midwest.”

Peirce brought the Brandon Teena idea to Corinne Jacker. Peirce had many wonderful film teachers — director Miloš Forman; screenwriter Paul Schrader, a name well known to a Scorsese nut like Peirce (“Paul taught us that you need ten years’ distance before you can tell your own story, and even then you should aim to transform it, find a cover for it, as he did in Taxi Driver”); Serbian director Emir Kusturica; and Ralph Rosenblum, editor of Annie Hall, to name a few — but it was Jacker, her thesis adviser, whom she had to persuade.

Peirce had reason to be optimistic. Here was a story about someone who wanted to dress like a man and date girls because that’s who that person was.

Again, Jacker balked.

“Now this person has two needs,” she said, “and that doesn’t work. You need one need. Does she want to be a man or does she want to be a lesbian?”

“Well, I don’t know,” said Peirce. “She seems to want to be a guy, or to dress like a guy, and she seems to want to be with women; she seems to want both, and I’m not sure which one came first or which one is more important. I don’t think it’s an either–or proposition. I think this person needs both.”

“Kim, you can’t just follow the truth. You have to shape drama.”

“I know, I know,” Peirce said, “but there must be a way dramatically that this character can both want to be with women and dress like a boy. Because I do.”

Jacker said, “That’s the truth. That’s still not one dramatic need.”

Peirce understood. She had to find the one need that encompassed Brandon’s behavior. As she sat down to write the script, it came to her that what Brandon really craved was love and acceptance. Dressing as a man and being with women weren’t Brandon’s needs; they were the means to satisfy his need.

Peirce made Boys as a twenty-minute film for her graduate thesis project. It was a troubled venture. Her producer left in the middle of it, and his replacement stole Peirce’s money and racked up car-rental bills and parking tickets. Peirce was desperate. Her life savings were gone and she had no producer. She did end up with gorgeous dailies, but didn’t have the final scene where Brandon dies.

Worse, her dailies — her raw, unedited footage — were still at DuArt, a postproduction facility on West 55th Street. Peirce couldn’t afford to get them out.

It was then, in 1994, that she was introduced to Christine Vachon.

Soon to found Killer Films, Vachon was the hottest indie producer in town. She’d made Rose Troche’s Go Fish and Todd Haynes’s Poison, with Haynes’s Safe and Larry Clark’s Kids set for release. Vachon, too, yearned to tell the Brandon Teena story. Through art-world friends, she had caught wind of Peirce’s project.

The producer invited the film student to her East Village office. Peirce was thrilled. It was a huge opportunity. But she had nothing to show. No short film, no feature.

She went to see Vachon anyway, thinking, “I’ve gotta get my goddamned dailies out of DuArt. Who’s gonna pay for that?”

At Killer Films, Peirce and Vachon sat down to talk. Peirce told Vachon about her own passion for the story. She said that though she had made a short, which was all she could afford, she’d realized while shooting it that it was meant to be a feature. Would Vachon like to see the dailies so she could know what she, Peirce, was up to?

Vachon was game. She sprang the dailies from DuArt and looked them over.

“Christine thought they were good,” Peirce recalls. “But she agreed with me: why would we pay to finish this as a short if we can make it as a feature?”

Five years later, they did.

Boys Don’t Cry went on to win dozens of awards from film-festival juries and critics’ societies, and earned Peirce a reputation so assured and enduring that, a dozen years later, as MGM discussed the resurrection of Carrie, the president of the studio’s film division, Jon Glickman, remembered Peirce and Boys Don’t Cry.

“Stephen King was incredibly sophisticated and ahead of his time, projecting what female power was going to do,” Peirce says of King’s 1974 novel, published a year after tennis player Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs in their “Battle of the Sexes” and two years after the advent of Ms. magazine. “Both De Palma and King were looking ahead to what happens when women have power. I’m making this movie after women have power, so what does that look like?”

Peirce has argued for the book’s feminist aspects — the channeling of the fear of women’s power, the centrality of the female characters — but it’s clear that her Carrie will speak in ways that its predecessors did not and could not.

And so, curious, eager, and a little nervous, we take our seats and silence our phones. What will this Carrie be like? How will audiences respond? What will it all mean for Peirce?

The lights go down. We are in the dark, as we have been for months, for years, waiting for the return of the girl with the hidden powers.

“If you start out with a secret,” Peirce says, talking about dramatic structure, “then obviously, over the course of the movie, that secret will be exposed. That exposure is generally the crisis point. What I’m finding in my movies is that after the second-act crisis, the third-act turn is, ‘How do you deal with the fact that your secret has been exposed?’

“That’s the new life for the character.”