If you ever walked past the artisinal groceries and flashy new high-rises on Wythe Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, you might not have noticed the National Sawdust building. Except for a growing graffiti mural and some sleek, rectangular windows sliced into the side, it doesn’t look like much. But inside the weathered, century-old brick exterior, where workers once produced kiln-dried hickory sawdust for smoking meats, lies a jewel of a space, the soon-to-open home of a nonprofit concert hall with a mission: to create a haven for promising musicians and composers in a neighborhood where space for artists is increasingly out of reach.

“We want it to be an oasis,” explains architect Peter Zuspan ’01CC, ’05GSAPP. Zuspan, along with Stella Lee ’00CC, ’05GSAPP and Laura Trevino ’07GSAPP, runs the Williamsburg-based architecture studio Bureau V, which has been working for the past seven years to design and construct National Sawdust. “We want it to be a place where something serious could happen, where really new music is heard for the first time. But we’re also hoping that the hundred-year-old building with [graffiti] tags all over it will undo a little of the formality of that.”

For Bureau V, the project is about far more than just blueprints and building specs — it’s the first embodiment of the young firm’s holistic philosophy, a way out of what Zuspan calls “the world of myopic architecture.” Zuspan, Lee, and Trevino are not only designing the space and overseeing its construction: they also signed the documents establishing the nonprofit and sit on its board. They’ve even had a hand in the programming — helping to host concerts while the building is still under construction.

“We’ve gotten way more involved than architects normally would,” Zuspan says.

“The nonprofit and the building grew together,” agrees Trevino. “It’s unconventional in many ways, but being so involved in the development of the organization also changed the idea of how the space would work.”

Zuspan, who acts as Bureau V’s spokesman, moved to the neighborhood roughly a decade ago, when brick warehouses were the norm, rather than the glass behemoths that are now popping up on every corner. He has the lean, limber build and blue-steel gaze of a fashion model (he and his Bureau V partners were once in a Cole Haan ad). A bold, hexagonal tattoo (a rendering of the universe by utopian architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux) is visible through the buzzed hair on the back of his head.

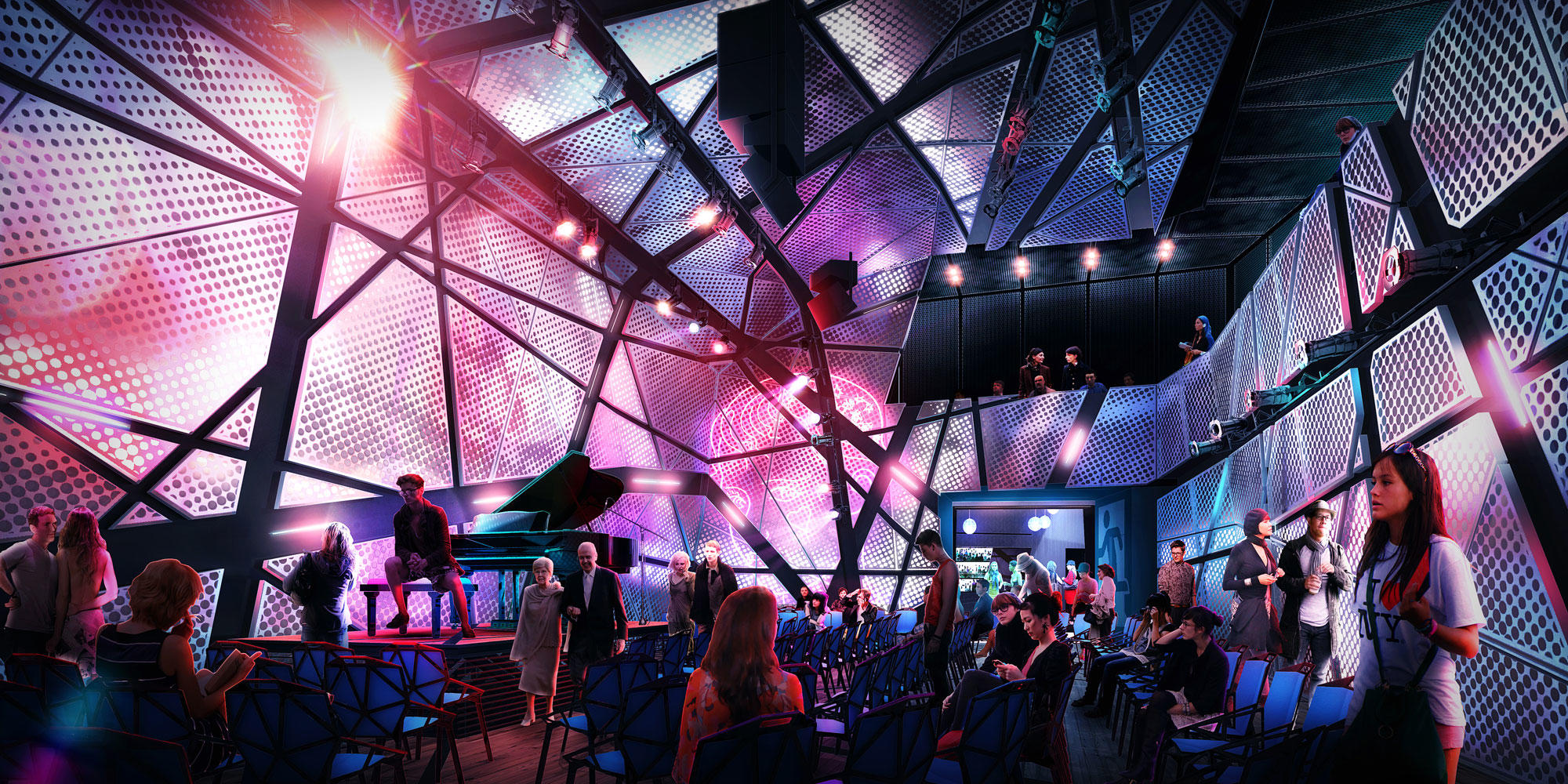

Walking through the building five months before the hall’s planned opening, Zuspan points out some of the unusual design features — for example, the metal beams that crisscross the stage, creating a dazzling web of shadow and light. These make it hard to notice that the thirteen-thousand-square-foot venue is actually just one big room, modeled after an eighteenth-century chamber-music hall. “There’s no fly space, there are no wings, there’s no backstage, there are no trap-doors,” Zuspan explains.

This simplicity is what makes it so special. It’s a Swiss Army knife of a music venue, a space that can be used by musicians in many ways, from recording to performance to practice to experimentation. Working with a team of acoustic consultants from the engineering firm Arup, whose list of projects includes the Sydney Opera House and the Beijing National Stadium, Bureau V calibrated the room so that it can host a seventy-piece orchestra or an intimate duet. The brick walls are lined with panels made of perforated metal and fabric, which conceal AV equipment, an installation that is, in Zuspan’s words, “visually opaque but acoustically transparent.”

In order to minimize structure-borne noise, a necessity for making professional recordings, the team built the floor of the venue out of concrete blocks on springs, which absorb the building’s vibrations. There’s also an additional recording studio and a full-scale kitchen — allowing the venue to cater full dinners — and a two-story restaurant.

Aside from making the space more versatile, Zuspan hopes that the design will also improve the audience’s experience of the music. The chamber hall can accommodate up to 170 seated guests or 350 standing ones, and no one is ever more than seven or eight rows away from the performers. “Since this is just a room rather than a proscenium or a stage, there’s not that distance between you and the audience,” Zuspan says. “Breaking down that fourth wall and forging a connection between the performer and the audience is also one of the goals.”

Zuspan has been thinking about these issues for years: as both an undergraduate and graduate student, he studied music as well as architecture. His senior undergraduate thesis was on the work of Iannis Xenakis, an architect-engineer who was also a composer.

“One of the great things about Columbia’s undergraduate architecture program is that you’re getting kids that approach architecture in this very liberal-arts way,” says Zuspan, who also teaches at Columbia part-time. “You watch these students bring what they’re learning in other classes into their studies. So you’ll have someone taking political philosophy and then translating those ideas into the form of a building.”

Though they both attended Columbia College, Zuspan and Lee didn’t meet until their first year of graduate school. During their final semester at GSAPP, they worked on a project for architecture professor Hani Rashid reimagining the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Manhattan as a museum of cinema special effects; both Lee and Trevino would go on to work for Rashid’s architecture firm, Asymptote, after graduation.

In 2007, after spearheading several international projects with Asymptote and leading the design of the Alessi flagship store in SoHo, Lee was ready to go out on her own. She convinced Zuspan, who was working as a designer at Diller Scofidio + Renfro and as an adjunct professor at Columbia and Barnard’s undergraduate architecture program, to cofound a studio with her and Alexander Pincus ’05GSAPP. Pincus left shortly thereafter to establish his own studio. Trevino, who graduated from GSAPP two years after Zuspan and Lee and who had worked with Lee at Asymptote, joined Bureau V in 2011.

Though all three principals were educated at Columbia, Lee was also conscious of their differences. Trevino had worked as a consultant for an urban-planning agency in her native Mexico and independently designed buildings there and in Asia. “We’re culturally very different,” Lee says, “which is occasionally a source of friction but also really enriching for our studio.”

Initially, the firm had to think creatively to find projects. “When you’re starting out, it’s tricky,” Zuspan says. “Our first projects were definitely self-initiated, not commissions. In the beginning you have to build a portfolio with these smaller ideas.” The architects collaborated with American fashion designer Mary Ping to make a pop-up installation for her conceptual label Slow and Steady Wins the Race. They also worked with musicians Arto Lindsay and Micah Gaugh on performance pieces.

Still, they wanted to land something bigger. In 2008, they were introduced to former tax attorney and current composer and classical-organ enthusiast Kevin Dolan, who wanted to create a venue that would protect some of the creative spirit of Williamsburg from the ravenous realities of real-estate interests. With Zuspan’s musical background and the studio’s commitment to the neighborhood, it seemed like the perfect fit. Before space was even secured, they began drawing up plans.

“We had a three-dimensional model of the place, not knowing where it would go. My partner and I were walking around the neighborhood looking for properties,” Zuspan says. “At the time, I lived on North 8th [two streets away], so I immediately saw the sign for this space when it went up.”

Dolan acquired the space for $2.3 million in 2009. By the time the building conversion is complete, it will have cost a total of sixteen million dollars. Dolan put up eight million dollars for the space, and the rest has been raised by investors and donations, including $105,165 from a Kickstarter campaign.

Building anything in Williamsburg in 2015 necessarily raises questions about who is being pushed out to make way for this new construction — questions to which Bureau V and the nonprofit are sensitive. Part of the reason they chose to preserve National Sawdust’s historic brick shell — which was costlier than razing it and building from scratch — was in reaction to the soaring new condo buildings everywhere. “There’s a little bit of defiant preservation happening there,” Zuspan says. “I do think there’s a positive aspect to maintaining something old in this neighborhood,”

“We’re bringing an amenity to the neighborhood,” he adds, “and that could allow property values to go up a little more. But part of our model, too, is to create audiences and then channel all those ticket and liquor sales into supporting young artists. We’re trying to make a new space smartly, and do it with some degree of awareness. And to have it be something that people don’t want to tear down immediately.”

The creative director of National Sawdust is Paola Prestini, a noted multimedia artist and composer, who has put the weight of her classical connections behind the project. National Sawdust will host three concerts in the New York Philharmonic’s contemporary Contact! series, and is working with Carnegie Hall to host some of their young-artist initiatives. Its advisory board includes such musical heavyweights as Suzanne Vega ’81BC, Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson ’69BC, ’72SOA, and Nico Muhly ’03CC.

Certainly, National Sawdust will be able to draw some of its audience from those who might regularly visit the Brooklyn Academy of Music and Lincoln Center. But the space’s lineup is more eclectic than that of either of those two arts staples. The list of program curators announced for the space include soul singer Martha Redbone, steel-pan composer Andy Akiho, puppeteer-musician team Julian Crouch and Saskia Lane, and electronic composer R. Luke DuBois ’97CC, ’03GSAS. There will also be twelve artists-in-residence and four composers-in-residence that will cycle in on an annual or biannual basis.

Though the space has yet to open, the nonprofit has already staged several successful shows there, at different stages of the building’s evolution. In September 2012, National Sawdust hosted a concert called “Skyful,” which ended with butterfly-shaped kites drifting up through the then-roofless building; New York magazine critic Justin Davidson ’90GSAS, ’94SOA included it on his list of top ten classical concerts of the year.

While public excitement for National Sawdust’s opening builds, Bureau V has been working on several smaller projects that also exceed the traditional bounds of their discipline. The team collaborated with outside designers on the execution of certain details of the interior of National Sawdust, like a marble-and-neon chandelier that will hang in the entrance. In 2013, they also designed a capsule menswear collection. And they recently submitted plans to a design contest sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art for converting two concrete artillery shelters in Fort Tilden, Queens, into a contemporary-art museum.

“We’re trying to get our hands dirty doing a lot of things,” Zuspan says. “The historic model of the architect was a polymath ... If you look at the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius and other classical sources, architecture is the mother of the arts. You have to dabble in all these different fields in order to know what’s going on.”

After the completion of National Sawdust, Bureau V has plans to start on a furniture collection. It will also begin work on the residential building next to National Sawdust that Dolan owns. In future, there is talk of designing a single-family home, or maybe an opera set. But for now, the team is preparing for National Sawdust’s October opening. “It’s pretty much a dream project,” Zuspan says. “We feel so lucky to have been able to be a part of it. We’re excited to see how people use the space in ways we haven’t even imagined.”

Watch the video of “Skyful” concert at National Sawdust: