In the comic book version of Steve Duncan’s life, Duncan, aka Spelunkin’ Duncan, aka Tunnel Man, aka the Scholar of Subterranea, would have powers of X-ray vision: he could climb to the top of the Manhattan Bridge, look out over Gotham, and see right through the streets, the slabs of rock, into the ancient underbelly of subway tunnels, sewer lines, steam pipes, ghost stations, aqueducts, and buried rivers.

It’s not far-fetched. Duncan has indeed ascended the Manhattan Bridge (“It’s graceful, it’s beautiful, but there’s no easy way to get up it”), for that matter all the bridges around Manhattan, and is on a mole man’s terms with the netherworld of arteries beneath New York, London, Paris, Odessa, and Naples, among others. “It’s easy to find history,” goes his mantra. “The hard part is to find a different perspective on it.”

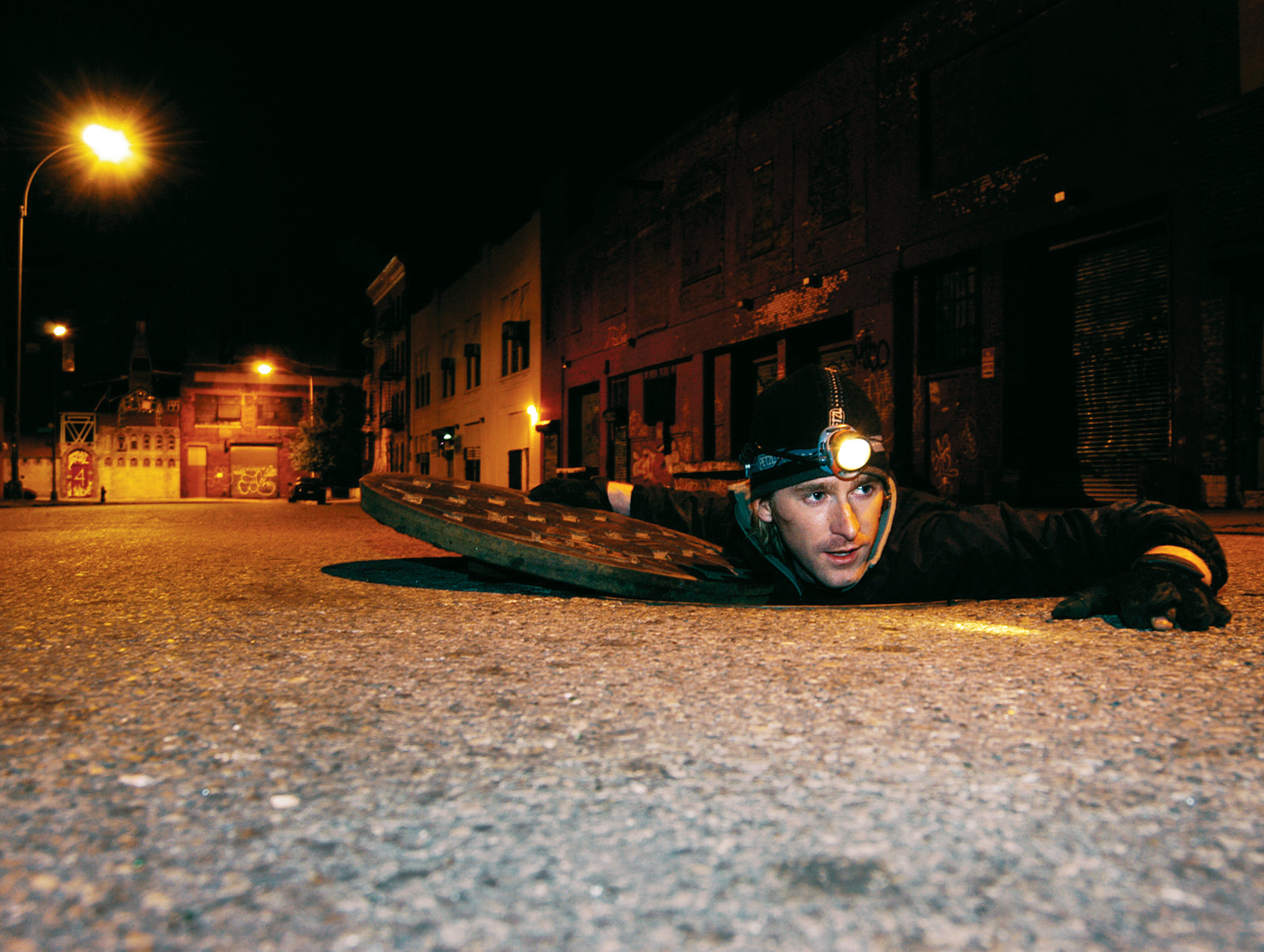

Duncan, 31, is an urban explorer, a guerrilla historian of infrastructure, for whom the multicolored layers of paint peeling off a beam on a subway platform, or the bright orange water oozing up from a track bed, provides the urban variant of Emerson’s “wild delight” that fills one in the presence of Nature. Nocturnal by temperament and expediency, Tunnel Man waits until the express trains stop running to slip around the end of a platform and into the unlit caverns of an abandoned transit project whose substance confers meanings that a book cannot. In spirit, he’s kin to those carefree wildlife adventurers who get up close to grizzly bears, his rugged enthusiasm cloaking the seriousness and volition of the solitary seeker. His nemeses are rain, tides, certain bacteria, the third rail, cops, and gravity. Once, in a storm drain in Queens, he got caught in a hurricane-driven tide, was permeated by pathogens, and almost lost his hand. He has been face-to-face with hordes of rats, cats, and cockroaches. He has used grappling hooks to surmount the crumbling superstructures of world’s fairs, has felt the cushion of wind, that warning breath, that precedes the sound of an approaching train, has emerged at night from heavy-lidded manholes into the middle of city streets, and, at sunrise in Paris, in the belfry of Notre Dame, was present at an unauthorized bell tolling that brought a swift visit from la police nationale.

“When I started exploring, it was all about the thrill,” Duncan says with a mellow southern lilt, “but over time, the stories behind the places became far more important. When I tell the story about going down to the underground rivers in Moscow, for example, the highlights are the moments of fear and of almost getting arrested. But what I think about is having been in this river underneath Red Square, having seen this thing that I had previously seen only on maps from 150 years ago, and that most people will never see. That deeper sense of seeing and understanding a city is what matters.”

Duncan grew up in the Washington suburb of Cheverly, Maryland. His mother was a practicing Catholic and took in stray animals. The house was filled with dogs, cats, birds, ferrets. As a kid, Duncan read heaps of science fiction and cleaned a lot of cages. There was no television, no junk food, and, at St. Anselm’s Abbey School in D.C., where Duncan spent his high school years, no girls. “My mother dragged me to church every Sunday,” Duncan says, “and the one thing I was ever really solid and strong about as a young person was that I was not going to be an altar boy.” That was about the extent of his youthful rebellion. Never did he sneak into the boiler room of St. Anselm’s. “I was too timid to get in trouble,” he says.

In the shelter of his childhood, Duncan was captured by the fantasy worlds of Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Isaac Asimov, William Gibson, Roger Zelazny, and Douglas Adams, so that when, at 17, after being accepted to Columbia, he came to New York for the first time, it was as if the most elaborate cityscapes of his imagination had met their match. “I fell in love from the moment we crossed the George Washington Bridge,” he says. “I was blown away by the engineering and physical complexity of New York, partly because I’d read about these imaginary constructs in books.”

Columbia would prepare Duncan for his own journey to the center of the earth, supplying him with the crucial event that, like Peter Parker’s spider bite, or the bat coming through Bruce Wayne’s window, allowed him to become — Tunnel Man!

It was at the end of his first semester, during finals week. Duncan, who planned to major in English and engineering, had just learned of a study project that could only be done on a computer program at the math lab. He ran to Mathematics, but by then it was midnight and the building was locked. Frustrated, Duncan returned to Carman Hall and sought out a fellow student, “one of those crazy, jaded New York kids who seemed to know everything about the campus,” and asked him if there was a way to get into the math lab after hours.

There was.

“I’d heard these bits of gossip or myth about the Columbia tunnels, about the Manhattan Project,” Duncan says of the systems of utility conduits beneath Columbia’s campus, “and I knew they had some kind of reference in reality. I just wasn’t sure exactly what.”

The kid led Duncan to an entrance at one of the physical plant areas and said, “Go in that direction and you’ll come to the main tunnel. Take that, and follow the steam pipes.”

There’s always a dragon to be slain. Peter Parker was bullied as a teenager. Bruce Wayne lost his parents to a killer. Steve Duncan, lanky and mild-mannered, stood at the threshold of the Columbia tunnels, gazing into the blackness. He was, and always had been, afraid of the dark.

The hard part is trying to find a different perspective.

“I figured if I could venture alone into this dark and terrifying tunnel, I could be proud of myself,” Duncan says. “There was the sense that if I didn’t push through with it, I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the eye.” Duncan reached Mathematics a changed man. He returned to the tunnels again and again.

“The tunnels are a wonderful microcosm of the built environment,” he says. “Exploring them was a hands-on way to understand things that are part of New York and all cities.”

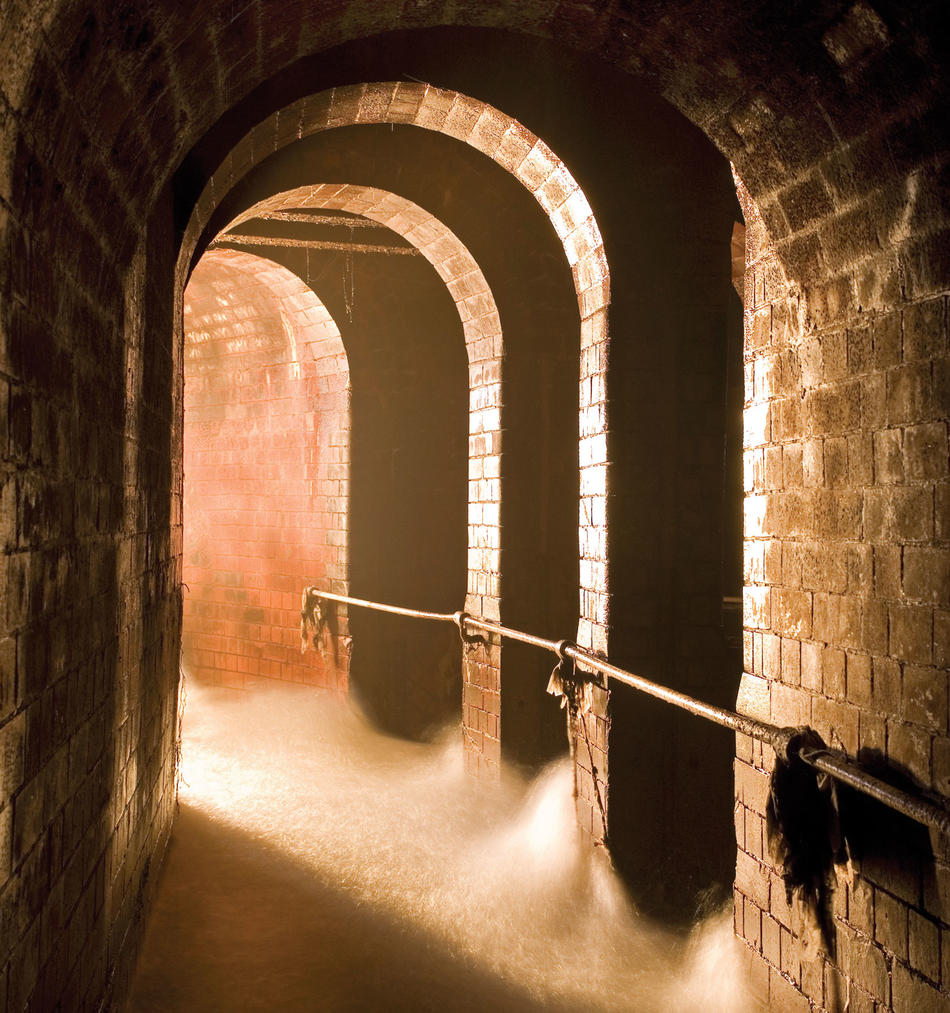

Duncan delved into other structures in the Columbia area, and became increasingly drawn to urban history as a field of study. He stood at the front of subway trains and peered out at the rusting anatomy and grand murals of Subterranea. He infiltrated the abandoned subway station at West 91st Street, and dug himself into the Riverside Park tunnel, which was built by Robert Moses in the 1930s, populated by hundreds of homeless people in the 1980s, cleared of human dwellers in the early 1990s, though not entirely, and is now used by Amtrak. (“I went through this little hole in the dirt, just squirmed through, and then suddenly found myself in a space the size of a cathedral.”) He got his boots wet in the canal under Canal Street, and shone his headlamp into the oblivion of the Knickerbocker Avenue Extension Sewer, built over a century ago to divert sewage from Bushwick into the East River.

Back on campus, Duncan took Kenneth Jackson’s class, The History of the City of New York. Jackson’s dynamic storytelling inspired the young spelunker to go deeper into his subject, in every sense. Duncan switched his major to urban history, and is now pursuing his master’s degree in public history at the University of California at Riverside. But the classroom, for Duncan, has no particular walls — or rather, those walls can sometimes be 50 feet below the sidewalk. Duncan recalls riding the subway in his early New York days: “I wanted to be able to put out my hand and touch the tunnel walls rather than just see them through a window. Things are more meaningful when there’s something you can touch or feel.”

The hard part is trying to find a different perspective.

In 2003, Duncan was hiking in Yosemite National Park when he had a minor fall. He injured his right hip. When the pain didn’t go away, he went for X-rays. He thought it was a pulled muscle, but it turned out that the hip was cracked. Additional tests revealed something more: an extremely rare, cancerlike syndrome called vanishing bone disease, in which the bone is mysteriously eaten away. At 25, Duncan had a new set of fears to wrestle with. He received radiation. His family prayed. The treatments were effective, and Duncan recovered normal functionality. “Nothing like spending a week on a pediatric cancer ward to make you realize how lucky you have it,” he says.

Duncan is now considered cured. The hip will have to be replaced in a few years — the lost bone does not regenerate — and Tunnel Man needs to be careful not to jump down from high places. “People tell me I shouldn’t do some of the stuff I do because it might get me killed, but I thought I was going to die from cancer. So if things are that arbitrary, why not do it?”

To which some might say, “Because it’s not always legal, sir.”

That notion elicits further glimmers of the Tao of Steve: “I see myself more like Robin Hood,” he says in his laid-back way. “I do what’s right, even if it doesn’t necessarily conform to the law. It’s a crime not to look at these amazing views.”

To fight this menace, Duncan has enlisted his visual gifts. Not X-ray vision (like Batman, the real-life Tunnel Man has no superpowers, just superior skills), but something close: an ability to capture beauty where it is most hidden.

“I got my first film camera in 2000 and was fooling around with it for years, without much hope,” he says. “I wasn’t interested in documentation; I wanted to replicate the sense of awe, capture the feeling of these inaccessible places. So one day I dragged a couple of friends who were amateur photographers down with me and we fooled around trying to figure out how to light absolutely dark space. It wasn’t until 2005 that I felt like I was taking any pictures worth keeping.”

Now he hardly goes anywhere without his Canon EOS 5D. “I want to share things that are amazingly beautiful, or sometimes not beautiful. Sometimes,” he says, “it’s just exciting to realize that there’s this giant 60-foot diameter brick sewer from the 1880s running under your favorite bar in Williamsburg.” Exciting and, to Duncan, edifying. “I think it’s worthwhile to understand your environment and where it came from,” he says. “Relics of the past and remnants of previous layers of urban development make you realize that the built environment around us was not inevitable, that there are different ways it could have gone, which helps us realize that we have an agency in how our cities develop.”

Duncan has presented slide shows of his work at venues in New York and Riverside, California. He has hosted the Discovery Channel show Urban Explorers and recently appeared on the History Channel as an expert on New York’s underground. His photos have appeared in exhibitions in New York, Boston, Washington, and Riverside.

Still, for Duncan, there’s nothing like the real thing.

“I would love it if I could take, one at a time, each night in a row, every New Yorker up to the top of the Manhattan Bridge and show them the view from there.”