Jerome Charyn, dressed in baggy midnight-blue corduroys and a faded brown leather jacket, approaches the gabled, white stucco, gingerbread-trimmed mansion that sits atop the third highest hill in the District of Columbia. From these heights you can see, four miles to the south, through the bare trees, the Capitol, its dome an apricot bell in the twilight. On the hill’s northern slope, in the Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery, the orderly ranks of identical white grave markers take on the buffed pink of Tennessee marble.

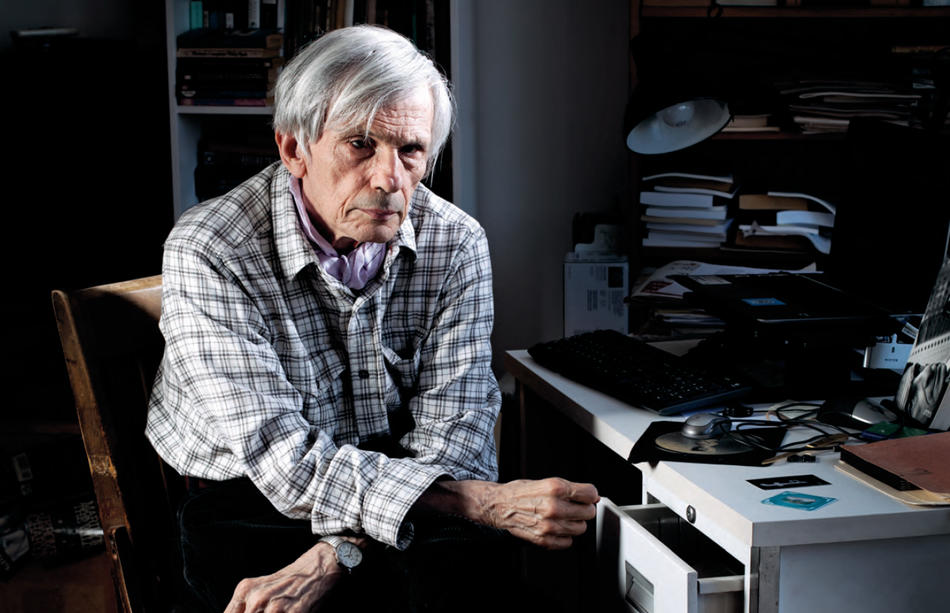

It is the eve of Lincoln’s birthday, and Charyn ’59CC has come here to talk about his latest novel, I Am Abraham.

The Gothic Revival mansion, called Lincoln’s Cottage, stands on the pastoral acreage of the Soldiers’ Home, an asylum established in 1851 to shelter veterans of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. Located about a forty-minute trot from the White House, this breezier elevation offered the president and his family some relief from the summer swelter of downtown. But not from the war: the adjacent cemetery was grimly busy, the dash of shovels within earshot of the cottage windows of the dark-browed, long-faced president.

Charyn enters the house and climbs the narrow wooden staircase. Upstairs, in a large, bare room with white walls and a hardwood floor, nearly fifty people have gathered on folding chairs to hear the novelist who presumed to speak as Lincoln.

Everyone thought I was crazy. Who the hell would want to write a novel in Lincoln’s voice but a madman? But what did I care — all I could do was fail. The question was, could I inhabit that voice?

At the lectern, the novelist opens his book. His gray hair sweeps across his head and over his ears. Deep creases bracket his thin mouth, shadows lurk in the divots of his Artaudian cheekbones. He could be a phantom of some nineteenth-century theater: the desperado in the black cape, peering over his shoulder. Or is it a magician?

He reads from his prologue:

“They could natter till their noses landed on the moon, and I still wouldn’t sign any documents that morning. I wanted to hear what had happened to Lee’s sword at Appomattox.” Lincoln is breakfasting with his son Bob, who, fresh from Lee’s surrender, sits in the Oval Office, his “boot heels on my map table and lighting up a seegar.” Charyn’s cannon bursts of imagery (“Mary appeared in her victory dress — with silver flounces and a blood red bodice. She’d decorated herself for tonight, had bits of coal around her eyes, like Cleopatra”), leading inexorably to the presidential box of Ford’s Theatre “all papered in royal red” — this overture announces, with high brass and offhand aplomb, the novelist’s stupendous purpose.

On the third draft, out of a kind of despair, I somehow entered into Lincoln’s persona, assumed his magic, his language; became him. You’d never be able to internalize it unless it possessed you in a demonic way.

“I leaned forward. The play went on with its own little eternity of rustling sounds. Then I could hear a rustle right behind me. I figured the Metropolitan detective had glided through the inner door of the box to peek at our tranquility.” Lincoln’s imagined tranquility at that moment is a daydream of a pilgrimage with his family to the City of David, where “I wouldn’t have to stare at shoulder straps and muskets. I wouldn’t have to watch the metal coffins arrive at the Sixth Street wharves.” The bullet strikes — and the novel bursts forth in a four-hundred-page flashback of Lincoln’s improbable life.

Hearing Charyn ventriloquize the sixteenth president in elongated Bronxese, in the house where Lincoln read his Shakespeare, worked on the Emancipation Proclamation, and played checkers with young Tad, plucks a democratic string: just as humble Lincoln could become the greatest of presidents, so a son of the Grand Concourse could enter that inscrutable soul with a music that Charyn — inspired by Lionel Trilling’s observation of American literature’s best-known voice as being melodized by the Mississippi and the “truth of moral passion” — imagined as a grown-up Huckleberry Finn. The same Huck Finn who says, early in Twain’s novel, “I felt so lonesome I most wished I was dead.”

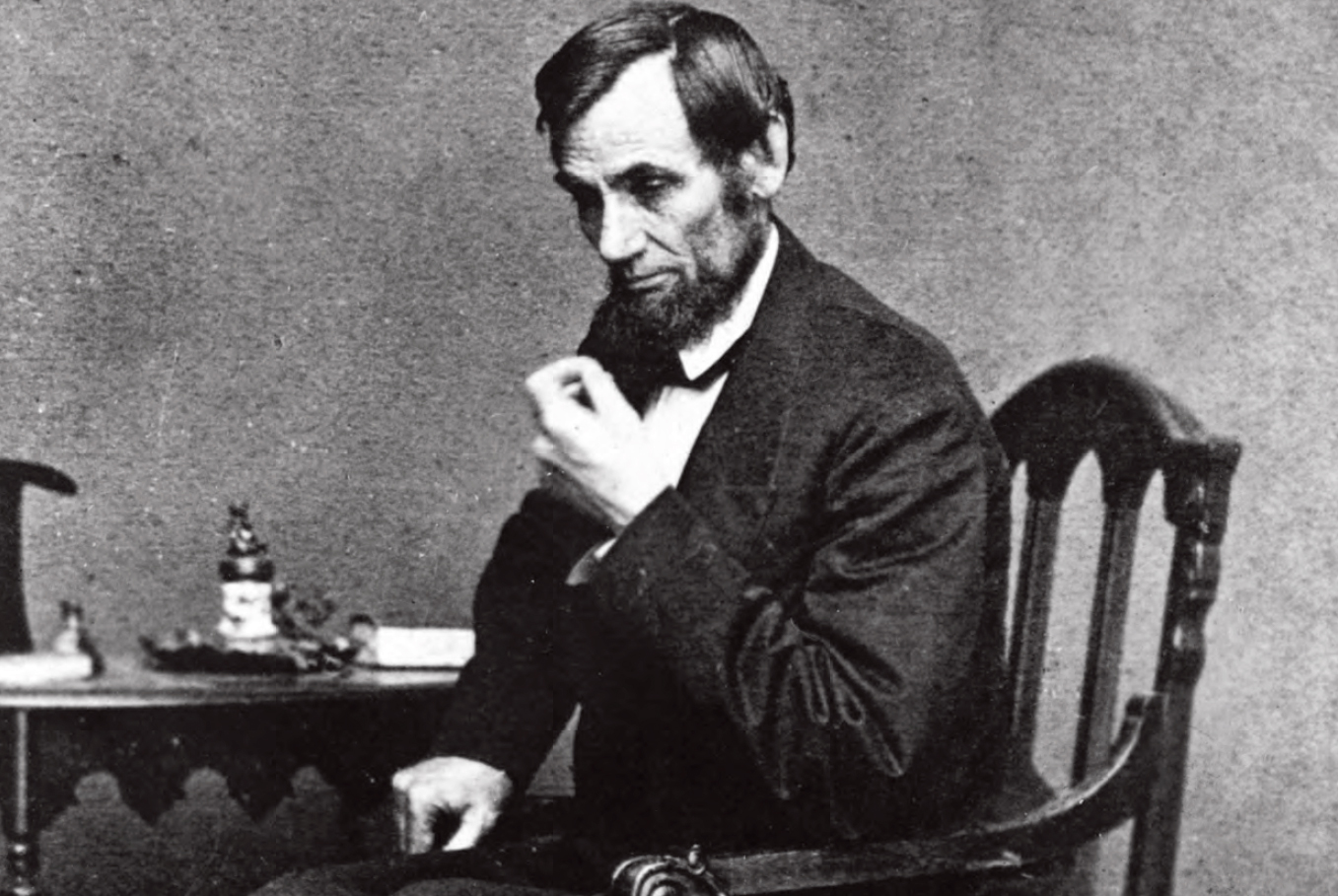

Once, when he was in his twenties, people were frightened that he would kill himself, so they took his razors away.

In Lincoln’s day, Charyn tells the audience, depression was called “the hypos” — what Melville’s Ishmael, in Moby-Dick, terms “a damp, drizzly November in my soul,” an affliction which, when it gets “such an upper hand of me,” impels him to take to the sea. Charyn, from his witch’s cauldron of words, provides his Abraham a pet name for his malady: the blue unholies.

You don’t suddenly become melancholic in your twenties. It happens very early, but you find ways of hiding it. Then suddenly you can’t hide it and you sort of break down, and part of the survival is admitting that you’ve broken down. I think this happened to Lincoln several times.

Charyn as a child was a brooding loner. His relatives had all been gripped by depression. When his own hypos came a-calling, Charyn took to the movie house, salving himself with grainy pictorial potions that he would later alchemize into prose. His home life was hell. His father, a furrier with a failing business, resented his younger son, who was the ruby of Mrs. Charyn’s eye. In his father’s eyes, the boy saw anger, jealousy, hostility — “he’d look at me like I was taking up his space.”

I do believe that Lincoln’s relationship with his mother was profound. He loved his mother deeply. We know he didn’t get along with his father, and that he had a lot of problems with his father.

The house in the Bronx was filled with taxidermied, fur-bearing animals. Charyn remembers bears. Bears all around.

When he was five or six, his father took him to see Henry Fonda in Immortal Sergeant. Afterward, on the street, Mr. Charyn asked his son a terrible question. He asked him which of his parents he loved more. What answer could a child give?

His father hated slavery, and a lot of Lincoln’s reactions to slavery come from his father. His father was also a great storyteller, and many of Lincoln’s stories clearly come from what he heard from his father. His father was a carpenter, and Lincoln was a great carpenter. His father taught him how to shoot, though Lincoln didn’t like to kill animals. He once killed a wild turkey and said, “I’m never going to kill another animal again.” Then he ends up being president of the United States, and having to kill hundreds of thousands of people.

The young Mr. Lincoln wrote a poem called “The Bear Hunt.” He is also the likely author of “The Suicide’s Soliloquy,” an unsigned poem written in the form of a suicide note, in which the narrator stabs himself in the heart.

Lincoln had two major bouts of depression: one was after the death of Ann Rutledge. He couldn’t bear the thought of the rain pounding on her grave.

Many scholars suspect Rutledge was Lincoln’s great love. In Charyn’s novel, the naive Lincoln has a minor sexual brush with the young barmaid that intoxicates him and upsets the delicate cart of his tender feeling toward her. When Rutledge dies of typhoid at twenty-two, Lincoln is disconsolate.

The second major attack, Charyn says, came when Lincoln broke off his engagement to Mary Todd, beside whose aristocratic majesty Lincoln felt like a rawboned yokel. Charyn doesn’t buy the notion of Mary as a hellcat who only terrorized her poor husband. To the novelist, Mary is the force behind Lincoln’s rise to office, a woman of brilliance and ambition who, as First Lady, is reduced, maddeningly, to the role of White House decorator.

I think he deeply loved Mary. I think he fell in love with her right away.

At forty, Charyn went through a breakup that fairly crushed him. Anguished and guilt-stricken, the novelist lay helplessly in bed for a month, in the cold clasp of the blue unholies.

Writing a novel is a literal dying. It’s a kind of death. Because it occupies you in an absolute, total, visceral way. It’s everything or it’s nothing; there’s no in-between.

(Charyn has died approximately thirty-four times. His first novel, Once Upon a Droshky, was published fifty years ago.)

After the talk, Charyn moves to an adjoining room and sits at a long table to sign books. A bitter night has fallen on the cottage and on the cemetery at the foot of the hill, its stones lit bone-white under a nearly full moon. Behind Charyn, a large wooden checkerboard rests on a small stand, the pieces the size of hockey pucks.

A signature seeker opens a copy of I Am Abraham and asks the author about Lincoln’s literary interests.

“Lincoln read the Bible, Euclid, Shakespeare, probably Bunyan,” Charyn says, and scratches his name on the title page. “He knew Shakespeare’s plays, saw them in Washington. Macbeth was his favorite. In the Spielberg movie, he quotes Hamlet: ‘I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.’ I love Hamlet. It’s really the source of everything for me. You take this murderer and turn him into a prince. He’s a murderer! He hears a ghost, he brings down a kingdom, he’s in love with his mother, he drives a girl to suicide — all out of hearing what he thinks is the voice of his father.”

It appears, says the signature seeker, that the poet of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address — and “The Bear Hunt” — had read the right authors: for Melville, too, with his damp Novembers, had read Shakespeare and the Bible.

“Melville may have read Shakespeare and the Bible,” Charyn says. “But his language really comes from the sea.”

The holy blue. Of course. The truth of it seems self-evident.

But what, then, of Lincoln? What was his sea?

Charyn considers.

“Lincoln’s poetry was deepened by the war,” he says. “His sea is the dying of the soldiers. Once the soldiers begin to die, his language deepens, and everything becomes a kind of dirge. He’s in perpetual mourning.”