On a cold, slushy morning in mid-December, Melissa Mark-Viverito ’91CC, the Speaker of the New York City Council, entered a school auditorium on the Lower East Side. It was a Saturday, and Mark-Viverito was dressed casually in jeans and a red sweater. She headed past the rows of bolted-down wooden chairs to the front of the room, where people from city agencies and legal-aid groups sat at long tables stacked with pamphlets covering topics urgent to immigrants: what to do if a federal immigration agent knocks at your door, your legal rights, and where to turn for help.

This information fair, a hastily scheduled addition to a monthly program, was sponsored by the New York Immigration Coalition, a nonprofit that has seen its budget triple since Mark-Viverito became council Speaker in 2014. Mark-Viverito, whose district includes the South Bronx and East Harlem, was alarmed by Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election, and sought to address the fear and anxiety that she saw spreading among the city’s estimated half million undocumented immigrants.

“We provide these services as a way to demonstrate our commitment to our immigrant communities here in New York City,” she told the few dozen attendees, most of them lined up at the lawyers’ tables. “We’re here to defend our values as a city against what is coming: an administration that does not share our values.”

Ever since Trump announced his candidacy with incendiary comments about undocumented Mexican immigrants, Mark-Viverito has been speaking up. She took immediately to the editorial pages — and to Twitter — to condemn Trump’s statements and his intention to cut off federal funding to “sanctuary cities” — jurisdictions like New York that restrict their compliance with federal deportation efforts and extend services to undocumented residents.

In the election’s aftermath, Mark-Viverito had no time for the dazed incapacitation that gripped many New Yorkers. “President-elect Trump’s irresponsible rhetoric regarding immigrants is an affront to New Yorkers and does not reflect our values, including our commitment to inclusion, compassion, and the rule of law,” she said in mid-November, as Trump’s victory was still seeping into the mental topsoil of the heavily Democratic city. “To our undocumented community, we are with you, we will stand by you, and we will protect you. You are New Yorkers, and we will not abandon you.”

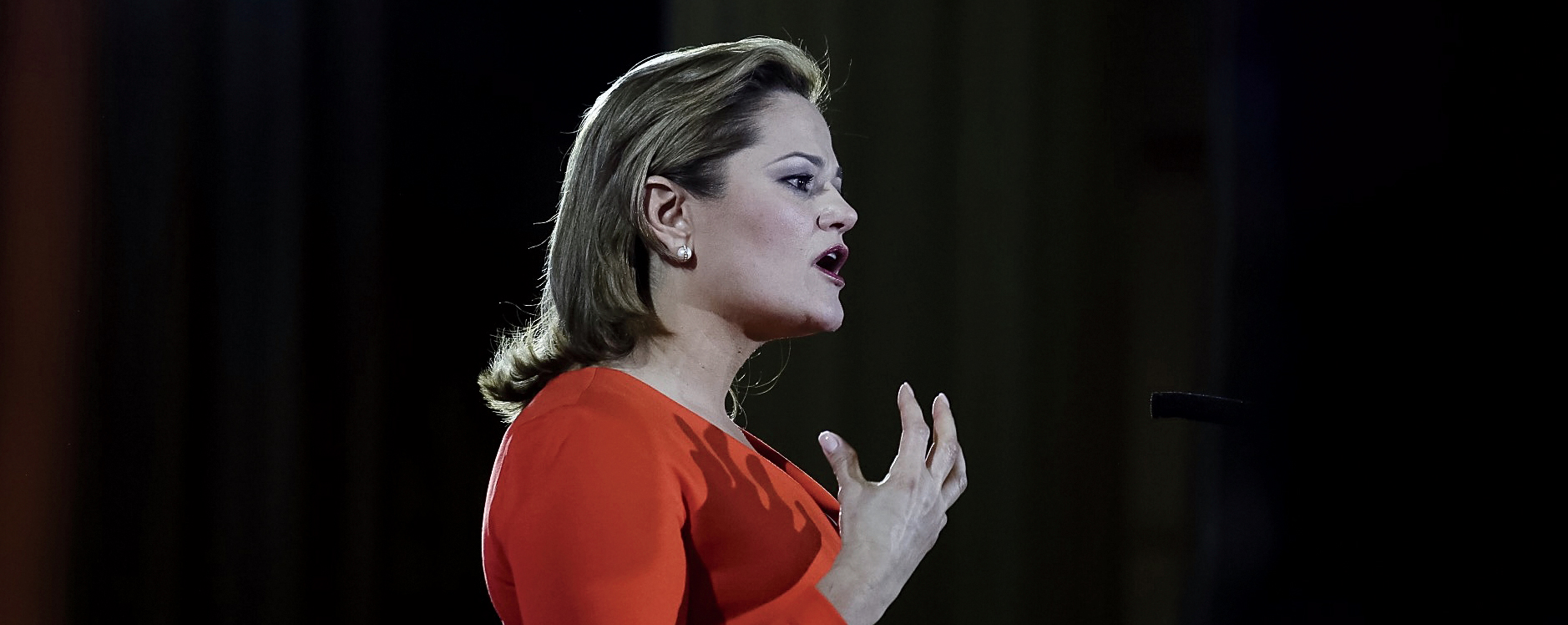

As the second most powerful official in New York after Mayor Bill de Blasio ’87SIPA, Mark-Viverito has been making herself heard — not with a bullhorn on the street, as in her activist days, but with a bully pulpit: the Speaker’s lectern in City Hall.

“We are in a state of emergency, and I’m not joking,” Mark-Viverito told Columbia Magazine shortly before Trump’s inauguration. “As a city we have to defend what we’ve achieved. This mayor and I — what we’ve done in terms of initiatives, public policy, the budget — have demonstrated our values: we embrace diversity, we’re an immigrant city, we welcome everyone who comes here to contribute positively. And those values are under attack. So we’ve got to be prepared. We’ve got to coalesce and push back, and there is no time to waste. We’re going to fight.”

The Road to Speakership

The New York City Council is the city’s lawmaking body. It consists of fifty-one elected council members representing fifty-one districts, and is an equal governing partner with the mayor. The council monitors the functioning of city agencies, makes land-use decisions, establishes spending priorities, and has final approval of the city’s budget.

The Speaker is elected by a majority vote of the council. The duties include appointing the leadership of the body’s thirty-five oversight committees, setting the council agenda, chairing meetings, and gaining consensus on legislation. Twice a month, council members from the five boroughs convene in the red-carpeted, mahogany-paneled, high-ceilinged council chambers of City Hall in Lower Manhattan, where they pass laws that affect all New Yorkers.

Mark-Viverito, forty-seven, was first elected to the council in 2005, and swiftly built a voting record consistent with her activist bent. She fought against the closing of senior centers and churches. She fought for paid sick days and for the rights of tenants to sue landlords for harassment. She fought to protect community gardens and public parks from private interests. She fought “Uptown New York” — a development project for East Harlem, backed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, which was drawn up without community input — and prevailed.

She was self-possessed, determined, and wasn’t afraid to take on unpopular causes. In 2010, she asked the council to support the parole hearing of Oscar López Rivera, a member of the militant Puerto Rican group FALN, which carried out bombings in New York in the 1970s and ’80s in the name of Puerto Rican independence. López Rivera had been convicted in 1981 of “seditious conspiracy” and was sentenced to fifty-five years in prison (he received another fifteen years in 1987 for conspiracy to escape). His supporters — including ten Nobel Peace Prize winners — considered him a political prisoner. Mark-Viverito, who was born and raised in Puerto Rico, had long been calling for López Rivera’s release. Her appeal to the council elicited an e-mail blast from Republican council member Dan Halloran of Queens, who wrote, “This terrorist, like all terrorists, should rot in jail forever.”

Mark-Viverito wasn’t deterred. In 2011 she led a rally near Bloomberg’s house in protest of the more than fifty thousand pot arrests the previous year, nearly 90 percent of which involved Blacks and Latinos. And with the Obama administration ramping up deportations, she cosponsored a bill, one of the first in the nation, limiting the city’s cooperation with US immigration officials. (This posture would be reinforced in late 2014 through a Mark-Viverito-backed bill that removed federal immigration officers from Rikers Island.) According to Mark-Viverito, Congress’s “abject failure” to address immigration reform — to resolve a complicated, long-unattended issue in a fair, humane way — meant that cities had to step up and lead.

In 2013, the term-limited council Speaker, Christine Quinn, joined the mayoral race, and the speakership was up for grabs. Mark-Viverito was entering her own final term with a reputation as a hard-nosed progressive lawmaker, and emerged from the pack as one of two leading Speaker candidates. Her rival was Dan Garodnick, a Democratic councilman from the Upper East Side. With the council sharply divided, Mark-Viverito embarked on what she calls “a bruising campaign.”

“The [New York] Post was brutal,” she says. “There were constant attacks. I think there were elements of racism — me being Latina and portrayed as ‘other,’ as a foreigner — and a resistance in the power structure to my progressive vision. I was portrayed as a threat to some extent. I had to withstand a lot as opposed to the other candidate, so it was hard. I knew the goal was to knock me down. But I have a tough shell, and I didn’t allow that.” On January 8, 2014, with the chambers packed with spectators and media, Mark-Viverito stood before the council for the vote. By a unanimous decision of the fifty-one members, Mark-Viverito was elected Speaker. The room broke out in cheers.

In her post-election remarks, Mark-Viverito said, “I hope that as young Latinas and Latinos are witnessing this moment, they are able to dream that much bigger and are inspired to work that much harder, because we have broken through one more barrier.”

Seeds of Action

When Mark-Viverito entered Columbia in the fall of 1987, the College had just graduated its first coed class. Beyond the gates, New York was beset with racial strife, AIDS, homelessness, crack, violence, financial chaos, and corruption. Bernhard Goetz had recently been acquitted on attempted-murder charges for the shooting of four African-American men on the subway after one of them asked him for money, and October 19 saw the Black Monday stock-market crash. And on October 22, at the Portsmouth Rotary Club in New Hampshire, an impassioned crowd of five hundred people, some holding TRUMP IN ’88 signs, listened as Donald Trump, the forty-one-year-old New York billionaire, said, “If the right man doesn’t get into office, you’re going to see a catastrophe in this country in the next four years like you’re never going to believe. And then you’ll be begging for the right man.”

That first year, Mark-Viverito had no time for politics. Not that she wasn’t interested: her father, Anthony Mark, was a politically engaged ophthalmologist in San Juan; and her mother, Elizabeth Viverito, was a feminist activist who had started one of Puerto Rico’s first female-led law firms. Both parents had been born in New York City, in the district that their daughter would one day represent, and they had passed on to her a keen sense of social justice. But as an eighteen-year-old Latina from a high-school class of forty entering the Ivy League circa 1987, Mark-Viverito had more immediate concerns.

“It was a little overwhelming,” she says. “Trying to figure Columbia out and navigate it and find my footing took some time.”

She encountered anti–Puerto Rican prejudice, too, something she wasn’t familiar with. Some was general, mostly variations on “they’re all on welfare and should get back on their boats and go home.” Some was personal. It got so that she considered leaving after her first year. But in the end, she says, “I decided to stick with it and push through.”

The experience led her to examine her identity and “figure out who I was.” She eventually became active with Acción Boricua, a campus group promoting Puerto Rican culture and education, “part of that greater movement at that time to try to diversify the curriculum, and put pressure on the administration to look at bringing in more faculty of color.” She also hosted “Caribe Latino,” a Latin-jazz and talk-radio program on WKCR.

Through her campus activism, she got to meet some of the city’s Puerto Rican leaders, like Richard “Richie” Perez, a founder of the National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights. She would go on to meet two other key influences: educator and feminist Antonia Pantoja ’54SW and Lorraine Cortés-Vázquez, the future secretary of state of New York. “A lot of the seeds that were planted growing up with my family really flowered at Columbia,” she says. “And that translated into becoming active in the city.”

From Private to Public

By the time Mark-Viverito graduated in 1991 with a degree in political science, New York had elected its first Black mayor, David Dinkins. Over the next decade, Mark-Viverito held leadership posts at Latino-centered nonprofits, volunteered at listener-supported WBAI as a producer and host, and continued on an activist path: agitating for more Latinos in government, organizing protests of US naval munitions testing on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, and rallying for the release of Oscar López Rivera. Her last job pre–City Council was as strategic organizer for Local 1199 of the Service Employees International Union, the largest health-care union in the US.

All of this would serve her as she entered public life. Twelve years after her first council win in 2005, she has become a leading voice not only for New York’s 720,000 Puerto Ricans and 2.5 million Latinos, but for Puerto Rico itself. (After the island’s 2015 debt default, she delivered a forceful speech on the council floor decrying Congress’s austerity-style remedies for a territory of 3.5 million US citizens.) And she has gained a national profile as a pugnacious critic of Trump and a fierce defender of immigrants.

She has also squared off with fellow progressive de Blasio, perhaps most notably over the “broken windows” crime-fighting philosophy of then NYPD chief William Bratton. Mark-Viverito argued that arrests for nonviolent offenses, such as having an open container of alcohol or being in a park after hours, took an unjust toll on people of color, and that the city, by handling such offenses in civil rather than criminal court, would save money, unclog the system, and enforce the law without ruining lives. The compromise she hammered out with de Blasio and Bratton — the Criminal Justice Reform Act of 2016 — is one of Mark-Viverito’s proudest achievements, one she said will “change trajectories for countless New Yorkers.”

Throughout her years in the tabloid glare of City Hall politics, Mark-Viverito has conscientiously guarded her privacy. Some details are known. She isn’t married. She has no children. She lives in an East Harlem townhouse.

But she doesn’t talk about that stuff. If she really wants you to know something, she’ll tweet it.

Twice during her speakership she used Twitter to make personal disclosures. In 2014, she revealed that she had human papillomavirus, a common sexually transmitted virus that can lead to cervical cancer; and last October, after the leak of a decade-old video in which Trump bragged about groping women, she was motivated to divulge that she had been sexually abused as a child. In both cases, she felt it her duty to use her platform to reduce stigma and raise awareness. “Yes, I’m an extremely private person,” she tweeted. “But this position has led me to understand I now have a bigger responsibility.”

A Reprieve

On January 18, 2017, the New York City Council convened. One might have expected a more pensive mood two days before Trump’s swearing-in, but City Hall was bubbly. Hugs, jokes, laughter among the gathering lawmakers. What was most striking about the atmosphere was the degree to which New York was eager to get down to New York business: passing laws regarding flower vendors, tax liens, arts programs, and vanpool regulations. Washington felt very far away.

The reporters filled up the pressroom for the pre-meeting news conference, and the seven council members who sponsored the bills stood in front of a backdrop of state, city, and borough flags. Then the side door opened, and Mark-Viverito entered; and as she greeted her colleagues, it became clear that the high spirits in the chambers radiated from the Speaker.

She was still on a cloud. The day before, President Obama ’83CC, in the waning hours of his presidency and after desperate appeals from Mark-Viverito and others, made the announcement: Oscar López Rivera would go free.

When Mark-Viverito got the news in her office, she cried. She had been involved in the case for much of her life, and Obama had so clearly been the last hope.

Mark-Viverito savored the moment. She shared her joy with the council and expressed gratitude to Obama in her council-meeting remarks. No one denied her the pleasure. The hands of the pendulum clock on the wall of council chambers were moving inexorably toward the new day.

Back to the Streets

A week later, Mark-Viverito stood in front of the same flags in the same pressroom. Her anger flared visibly. President Trump had begun issuing executive orders to build a wall on the Mexican border, deny federal grant money to sanctuary cities, expand deportations, and suspend immigration from seven majority-Muslim countries. Mark-Viverito strained for composure. “It’s very hard to contain myself,” she said. “I am extremely upset. So I don’t have time for fear. I want to defy, resist, stand up. That’s what we need to do as a city.”

That night, thousands of New Yorkers of all backgrounds and religions gathered in Washington Square Park, holding candles and signs in support of immigrants and refugees. New York was “demonstrating its values,” as Mark-Viverito had said it would. Things had gotten real, and there was no telling how any of it would play out.

Mark-Viverito was in the park, by the triumphal arch, in front of the microphones, where other city leaders, including public advocate Letitia James and comptroller Scott Stringer, had given strident, defiant speeches.

The City Council Speaker stepped forward, and her voice rose over the crowd’s cheers, echoing the cadence of history. Her message was simple and direct: “I’m here to say I add my voice to the resistance.”