"The collective experience of pain and hardship, suffering and sacrifice, has given African Americans a unique perspective from which our consciousness has been forged."

— Manning Marable, Living Black History

On the morning of April 9, 1968, a 17-year-old high-school senior from Dayton, Ohio, got off a city bus in downtown Atlanta and walked up Auburn Avenue to the Ebenezer Baptist Church. Above the church’s protruding blue sign, a solitary wreath hung on the red bricks. It was 6:30 a.m., and the young man, whose mother had sent him to cover the funeral for Dayton’s Black newspaper, was the only person around.

In hindsight, it seems logical, even inevitable, that the precocious teenager who was first on the scene that day should become, by the time he was in his early 30s, one of the world’s most perceptive and influential scholars of the Black experience. What sense of history, then, must have flooded Manning Marable’s consciousness in the gray Atlanta dawn? What possession of time and space as he stood alone on a desolate street where, in just a few hours, 150,000 mourners — students and senators, pacifists and militants, athletes and entertainers, capitalists and socialists, diplomats and governors and ordinary citizens of different colors and faiths — would gather for the largest public funeral in U.S. history? What grief, what visions, as he walked among the linked-arm multitude behind the mule-drawn wagon that carried the coffin of Martin Luther King Jr.?

The following winter, in his first year at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, Marable had another brush with history. This time it was in the pages of a book: The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

“The full relevance and revolutionary meaning of the man suddenly became crystal clear to me,” Marable later wrote of his conversion. “In short, the ‘King Man’ became almost overnight a confirmed, dedicated ‘X-Man.’” For Marable, Malcolm X was the “embodiment of Black masculinist authority and power, of uncompromising bravery in the face of racial oppression,” a prophet who “spoke the uncomfortable truths that no one else had the courage or integrity to broach.”

What Marable could not have known in 1969 was just how all-encompassing his obsession with Malcolm X would become.

"From the beginning of my academic life I viewed being a historian of the Black experience as becoming the bearer of truths or stories that had been suppressed or relegated to the margins."

— Manning Marable, Beyond Boundaries

The author looked like a million bucks.

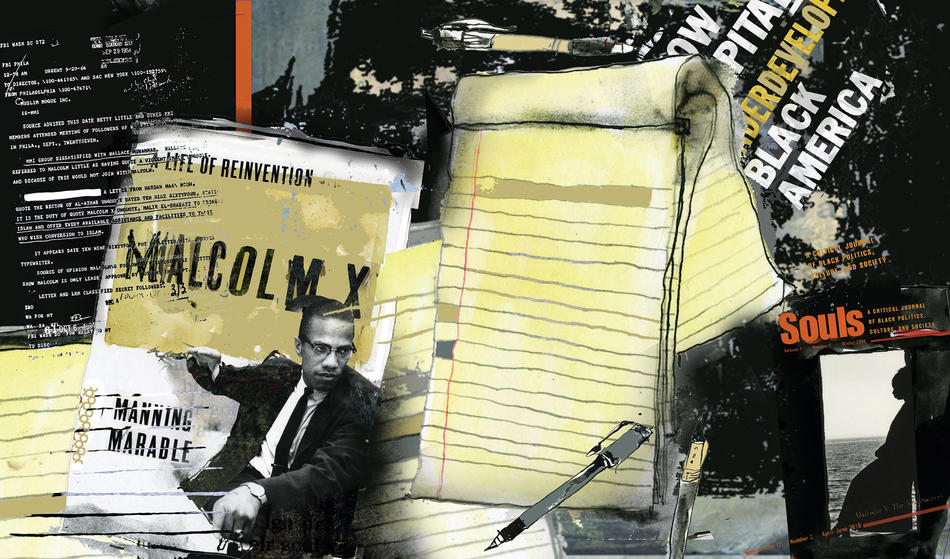

Trim, silver-haired, and neatly dressed, Manning Marable, the M. Moran Weston and Black Alumni Council Professor of African-American Studies and professor of history and public affairs at Columbia, arrived at Faculty House to celebrate the publication of Beyond Boundaries: The Manning Marable Reader, a collection of essays spanning Marable’s 35 years as a self-described “public historian and radical intellectual.” It was March 3, 2011, and Marable was in a period of unimaginable demands. In a few weeks he was scheduled to travel the country to promote a 500-page, much-anticipated work that he had completed with the help of an oxygen tank. The previous summer, he had undergone a double-lung transplant, the result of a lupus-like condition called sarcoidosis that had afflicted him for 25 years. (“He kept trying to pull himself out of sedation,” Marable’s wife and intellectual partner, the anthropologist Leith Mullings, later said. “He was determined to finish the book.”) Now, back on his feet, Marable stood at a lectern in the Presidential Room and reflected on his career.

“The foremost question that preoccupies my work is the nexus between history and Black consciousness,” Marable said. “What is the meaning of Black group identity as interpreted through the stories and experiences of African American people over time?”

As he spoke, Marable must have also been thinking of that other book, in which he explored this crucial question more profoundly than he ever had before. Kristen Clarke ’00LAW, Marable’s coeditor on a recent collection of essays titled Barack Obama and African American Empowerment, noticed Marable’s preoccupation at an event for their book held in February, at the Hue-Man Bookstore in Harlem. Later, Clarke would recall how excited Marable had been that night about the coming publication of Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, the monumental biography whose decade-long gestation had created a good deal of suspense: How would the inquisitive, methodical, leave-no-stone-unturned Marable approach the larger-than-life icon whom Marable himself called “the most remarkable figure produced by 20th-century Black America?”

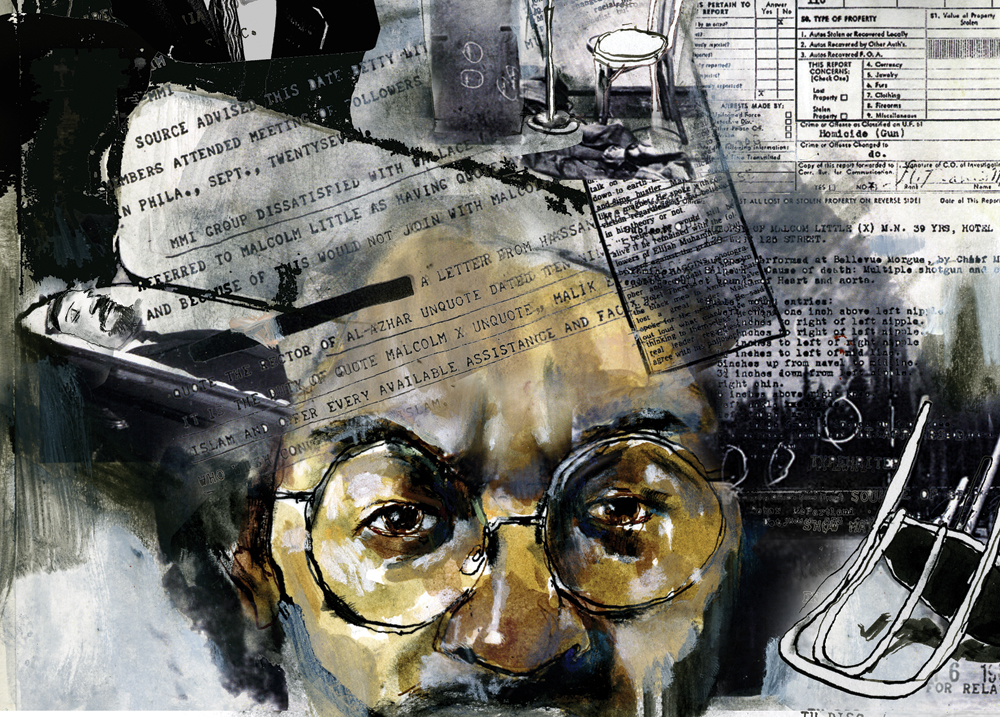

As the April 4 publication date approached, with all its unsubtle historic significance, Viking Books was buzzing with requests for advance copies and author interviews. This wasn’t surprising. Few figures in American history are as intensely loved, hated, and misinterpreted as Malcolm X, and Marable, never shy in his public engagement, yearned for the discussion that his powerfully written book was bound to set off. The pages contained an illuminating history of Black nationalism in America (including the Garveyism to which Malcolm Little was exposed as a child through his preacher father, Earl); details of Malcolm’s extensive travels in Africa in 1964; insights into his psychic complexities, divided loyalties, and political and religious evolution; his split from the Nation of Islam and his increasing profile on the global Islamic stage; and glimpses of the minister’s private life, if privacy could be said to exist for a man who, as Marable demonstrates to dramatic effect, was for years relentlessly spied on by the FBI and the NYPD.

But what really captured Marable, and fired his activist blood, was the mystery surrounding the events of February 21, 1965, when Malcolm X was gunned down at a rally at the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights. Three men, all members of the Nation of Islam, were arrested and convicted of the murder.

To Marable, however, something was wrong with the picture.

A week after his appearance at Faculty House this spring, Marable was hospitalized with pneumonia. His classes were canceled. On March 31, as bookstores were unpacking their cartons of Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention for their window displays, Marable went into cardiac arrest. Those who read the New York Times on April 2 would have seen a photo of Marable on the front page, with the stunning headline: On Eve of a Revealing Work, Malcolm X Biographer Dies.

Manning Marable was 60 years old. Three days later, the biography was released.

"Substantial elements of the Black elite do not discuss the unique problems of the “underclass,” either with whites or among themselves, because in doing so they would be forced to confront the common realities of racism that underlie the totality of America’s social and economic order."

— Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America

At one o’clock on Cinco de Mayo 2011, the day commemorating the defeat in 1862 of the French army in the Battle of Puebla in Mexico, a different sort of military triumph was being honored in Lower Manhattan. The streets around the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) on Hudson Street were barricaded, and people lined the sidewalks to watch the passing motorcade of President Barack Obama. The nation’s first Black chief executive was on his way to Ground Zero to meet with 9/11 families in the wake of the U.S. military’s targeted killing of Osama bin Laden. As the procession of armored cars crossed North Moore Street, the mostly non-Black spectators cheered.

Meanwhile, inside the offices of the LDF, Kristen Clarke was working on a legal challenge to a proposed redistricting plan in Louisiana. The LDF had determined that the plan was intended to diminish Black voting strength in the northwest part of the state, and Clarke was drafting a letter to the U.S. Department of Justice. But she was glad to take a moment in her office to remember her friend and mentor.

“I was in law school,” Clarke recalled, “but I was quickly drawn to IRAAS” — the Institute for Research in African-American Studies, which Marable founded in 1993 — “and was thrilled to learn that Dr. Marable was at the helm. Though I attended law classes, I spent most of my time at IRAAS, which I found to be a place that really fostered critical thinking.” There, in Schermerhorn Extension, Clarke taught an introductory African American studies course, was a senior editor for Souls, the quarterly journal of Black politics and culture that Marable established in 1999, organized conferences and symposia, and later coedited, with Marable, a reader on the racial implications of the Hurricane Katrina crisis.

“Dr. Marable was one of the finest examples of the scholar-activist,” Clarke said. “In 2000, for example, we convened a conference of hundreds of scholars from across the country on the prison-industrial complex, which looked at unfair sentencing, over-incarceration, and police brutality. People came away feeling empowered and motivated to work toward solutions. Under Dr. Marable’s leadership, IRAAS quickly became one of the finest think tanks of scholarship for African American studies.” Clarke would know, having majored in African American studies at Harvard in the 1990s under Henry Louis Gates and Cornel West. “Also, female African American scholars were very well represented at IRAAS, as they were in almost everything Dr. Marable did. It was always important to him that women had leadership roles, and it’s unsurprising to me that when he stepped down as director of IRAAS in 2003, he passed the baton to a woman, Farah Jasmine Griffin.”

Clarke then turned to Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. As a lawyer who once worked at Justice, Clarke had spoken with Marable about his concerns over the assassination. “It’s noteworthy that Dr. Marable got access to the Manhattan District Attorney files and other records that previous scholars had not had the opportunity to examine,” Clarke said, “which is why I think in this book we get a deeper and more complex portrait of Malcolm X than we’ve ever had.”

Those files contained data that reinforced Marable’s doubts.

“True to his scholar-activist principles, Dr. Marable very much wanted the biography of Malcolm X to be used as a vehicle to reopen what he viewed as a cold case,” said Clarke. “He came to believe that the individual who fired the kill shot — the initial shotgun blast that extinguished the life of Malcolm X — is still alive and has never been brought to justice.”

A week after Barack Obama’s visit to Lower Manhattan, one of the president’s most forceful critics stood before several hundred people at the CUNY Graduate Center to discuss Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. It was the eve of what would have been Manning Marable’s 61st birthday, and the speaker, the Princeton philosopher Cornel West — dressed as usual in a black three-piece suit, white shirt, and silver pocket watch and chain — dug into his homily with a heavy heart.

“Manning Marable was my brother,” West said devoutly. “And I loved my brother Manning. Dearly.”

West recalled meeting Marable 31 years before, to get the older scholar’s signature on his copy of From the Grassroots, one of Marable’s earliest works.

“As soon as I saw him, all I could do was give him a hug,” West told the crowd in his funky, ecumenical style. “He embraced me. He gave me confidence. He gave me en-cour-age-ment. I felt enabled and ennobled in his presence.” West, jazzman of ideas, syncopated his syllables, drew out sounds like a Selmer saxophone baptized in the river Jordan. “He had dedicated his life, and he did, he was faithful unto death in keeping alive the legacy of Frederick Douglass, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Sinclair Drake, E. Franklin Frazier, and yes, Marx, and Weber on a left-wing day — all of the great scholars who provided an analysis of the dynamics of power and structures and institutions but always connected the agency of those Sly Stone called Everyday People. To look at the world through the lens of those Frantz Fanon called ‘the wretched of the earth’ — that is, was, forever will be, the life and the legacy of my brother and your brother, Manning Marable.”

For West, who read the book twice, the biography raised a central question: “How do you talk about Malcolm X in the age of Obama?” He then contrasted the two leaders in relation to the poor, to the establishment, and to power itself, in ways unflattering to the president. “In the age of Obama,” said West, “the last thing you want to be is an angry Black man.”

That got some knowing laughs. West was just warming up.

“The condition of truth,” he said, “is to allow suffering to speak — that’s Manning Marable on Malcolm X. Which means a lot of folks who claimed to be in love with Malcolm will be unsettled by Manning’s text. That’s good. That’s called education.” Applause for that one. “Cut against the grain! Shatter the myths! Malcolm was a human being. Not pure and pristine, but a cracked vessel like all of us, who at the same time had a level of courage and vision and determination that was so rare, especially coming from the chocolate side of town, and especially among the subproletariat — the Black poor — the Black working poor. We’re not talkin’ about bourgeois Negroes like Martin Luther King Jr. right now.”

Martin was a great brother, West said, but “he decided to be in solidarity with the Black poor against the dominant tendencies of the Black bourgeoisie,” whereas Malcolm “was already there.” For evidence, West quoted Marable chapter and verse, and, hitting the blue notes, alluded to what for him were the “saddest lines in the whole text,” on page 268: The central irony of Malcolm’s career was that his critical powers of observation, so important in fashioning his dynamic public addresses, virtually disappeared in his mundane evaluations of those in his day-to-day personal circle. Especially in the final years of his life, nearly every individual he trusted would betray that trust.

West let the horror of that sink in. The betrayals, of course, had an ultimate consequence, and while West didn’t get into Marable’s suspicions about the murder, the speaker who preceded him that night did: Marable’s partner, Leith Mullings, the CUNY anthropologist who in the early 1990s had tried to bring Marable, whom she did not yet know personally, to CUNY — and who was still miffed, as she sometimes quipped, that he chose Columbia — had told the overflow crowd what many of Marable’s associates were telling the media.

“Manning was obsessed with the mysteries and unresolved questions around the assassination,” Mullings said. “Who gave the order, and who pulled the trigger?”

Which raised a slightly different question: How do you get justice for Malcolm X in the age of Eric Holder?

That same evening, in Kansas City, Missouri, a 54-year-old man named Alvin Sykes placed a three-page typed letter into an envelope. Back on April 5, Sykes had been at a friend’s house when a news report came on CBS about a new book that examined the assassination of Malcolm X. Later, Sykes would recall the announcer making reference to the author’s “last interview” — a poignant phrase. “That got me,” Sykes said.

Now, on May 12, Sykes, who was born to a 14-year-old mother and left school in the ninth grade, sealed the envelope and addressed it to a gentleman in Washington.

"All history conceals an a priori superstructure which promotes the interests of certain social classes at the expense of others."

— Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America

The spring semester was winding down at Dartmouth, and Russell Rickford ’09GSAS, an assistant professor of history, took a moment between student conferences to talk about his teacher, Manning Marable.

Rickford was getting used to this. One of Marable’s star students, Rickford served as editor of Beyond Boundaries and wrote the eulogy in the program that was to be handed out at a May 26 public memorial for Marable at Columbia.

“Marable came of age politically and intellectually in a moment of great social upheaval,” Rickford said. “His concerns reflect that moment. The Black studies movement, the civil rights and Black-power movements, the Black-arts movement, and anticolonial movements deeply influenced his political consciousness and the kind of questions that he would ask for the rest of his life as a historian, as a political scientist, and as a social critic.

“Many of the eulogies that have come out since his death place him in a lineage that includes W. E. B. Du Bois, who was his great hero, and probably the most important figure in Marable’s own political development. A close second is C. L. R. James, the historian and Marxist theorist, and to a lesser extent, Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist. But certainly, Du Bois reflects Marable’s commitment to scholarship in the service of social change and the Black liberation movement.

“Marable’s political consciousness and his fundamental political militancy were also informed by Malcolm. He always considered himself a sort of left nationalist — a Black nationalist who, as he reflected on the Black struggle in the United States and internationally, came to see class as the fundamental social contradiction and the primary source of inequality and racial oppression. As he matured, he became what I call an unhyphenated democratic socialist — a proponent of a deeply democratic, deeply egalitarian, nonsectarian, anti-Stalinist vision of socialism.

“Dr. Marable has an insider-outsider relation to Black studies and the Black community. I can’t think of anyone with a more encyclopedic knowledge of the Black experience. At the same time, he recognized that as a Marxist, he was representative of a minority constituency within the Black community. He understood very clearly the ambivalence that the Black working class had long felt toward the American Left. One of the main impulses of his scholarship and of his activism was to bridge that gap — not in a way that would impose upon Black workers these sort of arcane, derived ideas of Leninism or any other current of Marxism, but that would help to develop class consciousness within American workers of all colors — stimulate an organic Marxism in the heart of corporate capitalism. So he had that sort of duality. You might almost call it a Du Boisian double consciousness.

“Intellectually, Dr. Marable represents a structural critique of our racial democracy in a time when the public discourse is increasingly shaped by ideas of a postracial world — the notion that the civil rights movement solved the basic problems of racial inequality, a narrative that really enabled abandonment of the efforts to acknowledge and correct the institutional racism of the past. So Dr. Marable was writing and pursuing activism at a time when his message, his fundamental understanding of the nature of society, was, in many ways, marginal.”

Though maybe that message was becoming less marginal, somehow, in the age of Obama. At any rate, that week, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention hit number three on the New York Times best-seller list.

"Any criticisms, no matter how minor or mild, of Malcolm’s stated beliefs or evolving political career, were generally perceived as being not merely heretical, but almost treasonous to the entire Black race."

— Manning Marable, Beyond Boundaries

The halal food truck in front of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at 135th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard was doing good business on the evening of May 19. It was the 86th birthday of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, better known as Malcolm X, and inside the Schomburg, home to Malcolm X’s diaries, the Langston Hughes Auditorium filled up with a crowd that included Muslims, Marxists, nationalists, families, students, and even some admirers of Barack Obama.

The seven panelists took their seats on the stage, and the Schomburg’s director, Howard Dodson, entreated the audience to be respectful. Dodson knew that the evening’s program, billed as a “critical discussion” of Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, would not be a picnic for the author. Many in the audience, and certainly on the panel, felt that Marable’s inclusion in the book of speculation into Malcolm’s personal life — a possible for-pay sexual exchange with a wealthy white man during Malcolm’s hustling days (before he was reformed by the Honorable Elijah Mohammad), marital tensions in the Shabazz house — was sensationalistic at best.

Panelist Bill Sales ’66SIPA, ’91GSAS, an author and activist, said the book was “a revisionist tract” that was “compromised by the promotion market” and “speaks to the sensibilities of a white audience,” and that “Manning Marable has transformed Malcolm X into a Social Democrat.” Abdullah Abdur-Razzaq, a.k.a. James 67X, a close aide to Malcolm who had been extensively interviewed for Marable’s book, testified vociferously to Malcolm’s unswerving heterosexuality. Poet Amina Baraka recounted that when she heard that Marable had “slandered” Malcolm, “I was in agony. Why would Manning Marable repeat these rumors and speculations?” Amina’s husband, Amiri Baraka, revolutionary activist and former poet laureate of New Jersey, counseled that we must “include Marable’s consciousness” in our reading of the book, and suggested that Marable’s use of the word “sect” to describe the Nation of Islam was a fair indication of his biases.

Here, the problem of Marable’s absence, his inability to respond, was manifest, echoing the broader, more boundless emptiness left by his death. So it goes when a giant vanishes.

Then, during the Q&A period, a middle-aged woman got up and declared that she hadn’t read the book and had no intention of reading the book. Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz were her heroes, she said with piety, and they always would be. She seemed to expect an ovation, but most in the audience saw the problem in her statement, and no one applauded her words.

"As a Black historian, the question that came to me was, “How can the authentic history of Black people be brought to life?” By “authentic” I mean a historical narrative in which Blacks themselves are the principal actors, and that the story is told and explained largely from their own vantage point."

— Manning Marable, Living Black History

“Slow down, slow down,” the affable man with the bushy graying Afro said to Zaheer Ali, a Harvard graduate who was rattling off all the administrative things he had to do in order to matriculate at Columbia. “What are your research interests?”

Ali gathered himself. He had come to Professor Marable’s office in Schermerhorn Extension on a tip from a trusted source. Six months earlier, Ali was in a record store in Times Square when he spotted the sociologist Michael Eric Dyson, then a visiting scholar at Columbia. Ali introduced himself to Dyson, whom he recognized from TV, and Dyson agreed to read Ali’s Harvard thesis on Islam and hip-hop. Later, over dinner, Dyson told Ali, “You’ve got to talk to Manning.”

Now, seated across from Marable, Ali said, “I’m interested in doing a history of Temple Number 7 in Harlem.” That was the Nation of Islam mosque where Malcolm X was minister from 1954 to 1964.

Marable’s eyes brightened, and he smiled his underbite smile.

“You have to come here,” he said.

Ali did. It was 1999, and Ali entered the alternate universe of IRAAS, where research topics that “were on the periphery of what scholars would pay attention to,” such as CORE or the Black Panther Party, were treated as the important and relevant subjects that they actually were. Here, Black history was the country’s foundational narrative, “the core thread of the American experience,” in the words of Marable’s student Stephen Lazar ’06GSAS.

“Professor Marable helped us frame our work so that it spoke to the central issues in the field,” Ali said recently in the office of the Center for Contemporary Black History, a research center founded by Marable in 2003 to examine Black politics, culture, and society. “And it helped legitimatize the work academically."

In the summer of 2000, Marable hired the technology-savvy Ali to help him develop a multimedia study project on Du Bois’s 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk in conjunction with the Center for New Media Teaching and Learning. This led to conversations about doing a similar project on Malcolm X.

“In 2001, we began the Malcolm X Project (MXP), which was organized around gathering materials for the multimedia version of the autobiography,” said Ali. “We started interviewing people who knew Malcolm and worked with him, and that laid the early foundation for the Malcolm X biography.” Marable, always a generous provider of opportunities, funded students’ attendance at Columbia’s Oral History Summer Institute, run by Mary Marshall Clark; and when Louis Farrakhan, who was appointed minister of Temple Number 7 after Malcolm’s death, agreed to meet with Marable, who over the years had been critical of Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam, Marable brought Ali with him.

“It was an incredible meeting,” Ali said. “It lasted eight hours. Minister Farrakhan called Dr. Marable ‘a giant.’ We came back later and did a five-hour oral history interview.”

By meeting with members of the Nation of Islam, Marable and his team of some 20 student researchers were able to obtain a batch of old, decaying reel-to-reel tapes of Malcolm’s speeches in Temple Number 7. Marable sent the reels to a sound archivist, who rescued as much material as was possible.

“That provided a lot of insight into the kinds of speeches Malcolm gave while he was in the Nation that no one had ever reported on,” Ali said. “Dr. Marable would say, ‘You know, the MXP, it’s a way of life.’” Ali laughed. “It was like adventures in Black history. This was living history.”

After Marable’s death, Ali appeared on the major networks, talking about his mentor and Malcolm X, who, like Marable, died just before the publication of his book. (Whereas Marable saw and held the finished product, Malcolm X did not see the final Autobiography — a red flag for Marable, who believed that the book was posthumously edited to the tastes of the book’s coauthor, the liberal Republican integrationist Alex Haley.) Invariably, Ali’s TV interviewers turned to the assassination.

“Professor Marable had many questions in terms of irregularities surrounding Malcolm’s death,” Ali said. “For instance, typically, there would be two dozen police officers assigned to the Audubon Ballroom when Malcolm was speaking. On that day, there were two. And why did it seem that the police rushed to wrap this case up in the nice, neat narrative of the Nation of Islam versus Malcolm X? Dr. Marable suggests in the book that this was maybe to protect their assets — their informants and agents who were in both organizations.

“Then there is Talmadge Hayer’s affidavit. Of the three people who were convicted of the assassination — Hayer, Thomas Johnson, and Norman Butler — Hayer is the only one to have openly admitted his involvement, and at his trial he claimed that the other two men were not involved. But they all served time. Johnson died in 2009. Butler was paroled in 1985. Dr. Marable did speak with both Butler and Johnson, and felt the evidence suggested they were innocent. They were not caught at the scene; they were picked up a week or two after. Following the trail left by Hayer, who in a 1978 affidavit to attorney William Kunstler named his co-conspirators, Dr. Marable tried to track down who these other people were. By researching public records and aliases, he identified a person who is still alive and known in New Jersey. And that’s in the book.

“This person, whom Dr. Marable names, was later involved in a bank robbery with two accomplices. The accomplices were prosecuted. He wasn’t. And it seemed to Dr. Marable that his record was cleaned up.”

Eric Foner was convinced. It was 1993, and Foner ’63CC, ’69GSAS was chair of the search committee charged with finding a director for a new African American studies program at Columbia. One name kept popping up: Manning Marable, professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado, a renowned scholar and institution builder whose 1983 study of political economy, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America, became a touchstone for a generation of Black intellectuals. He earned his PhD in history from the University of Maryland in 1976, taught at Cornell and Fisk, was founding director of Colgate University’s Africana and Latin American Studies Program, and, after that, chair of the Black Studies Department at Ohio State University. Then he went to Boulder, where he got Foner’s call.

“Manning said, ‘Look. You’re in New York City — the institution should be geared to Harlem,’” Foner said recently. “Harvard’s program was geared to literature and culture. Manning was interested in public policy, history, and political science. He was a prolific and impeccable scholar who had a powerful vision of what IRAAS could become, and he rose to the top of our list.”

Marable accepted Columbia’s offer, and introduced himself to the University in his job talk in Schermerhorn Extension. His topic of choice was a controversial and little-understood Black revolutionary who didn’t get much play in academia.

“For him to come in and give a talk on Malcolm X was very bold,” said Robyn Spencer ’01GSAS, who was in the audience that day. “It said that this is a serious historical subject, that this person had an impact, not just on Black people, but on American history, politics, and culture.” Raised by working-class parents in a neighborhood in Brooklyn where “the New York Times was not even available,” Spencer was in many ways an atypical graduate student and had spent her first two years “finding my way at Columbia, figuring out the language, and how to be.” She’d been studying American history, and was interested in post–World War II Black social protest. “As someone who was working on the Panthers, I’d felt a little marginalized: Was this really history?” Then she saw Marable. You couldn’t miss him. “He looked like Frederick Douglass,” said Spencer, now an assistant professor of history at Lehman College, with a laugh. “He had this presence, and you wanted to know more.”

Then Marable talked about Malcolm X.

“He kept calling him ‘Malcolm,’ almost as if he knew him,” Spencer remembered. “It was a personal talk, and highly intellectual.” Marable also spoke about other things: incarceration, crack cocaine, structural inequality, and the challenge of transforming the relationship between Columbia and the community.

Spencer had been waiting for this. She asked Marable to be her adviser. He agreed, making her his first graduate student at Columbia. This was around the time of the Clarence Thomas hearings, when, as Spencer recalls, “Black community internal politics were on public display. Race loyalty versus gender loyalty: Was feminism relevant to Black women?” Marable had already answered the question emphatically in How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America in a chapter titled “Groundings with My Sisters: Patriarchy and the Exploitation of Black Women” — a point not lost on Spencer. “To have a male scholar say that feminism was a legitimate part of the Black political tradition, and not a side issue or a corrosive agent for distraction or something that white supremacy was trying to do to hinder Black resistance, was revolutionary.

“At the same time,” Spencer added, “Manning was open to critical engagement. He wasn’t doctrinaire. It’s not that he wasn’t confident, self-assured, and moving through the world with a sense of his own intellectual weight, but he still managed to solicit your opinion. He tried to dismantle some of those hierarchies, tried to struggle against his own socialization, and challenged you to struggle against yours.”

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.— James Weldon Johnson, “Lift Every Voice and Sing”

Eighteen years after Spencer and Foner listened to Marable’s job talk, they returned to celebrate his life. It was May 26, 2011, and the Roone Arledge Auditorium in Lerner Hall was packed with those who knew Marable best, and many more who had been inspired by him. Zaheer Ali was there. So was Russell Rickford. So was Kristen Clarke. Malcolm X researchers Garrett Felber ’09GSAS and Liz Mazucci ’05GSAS were there. Mayor David Dinkins made it. Congressman John Conyers of Michigan sent a telegram. Marable’s distinguished colleague, Michael Eric Dyson, had come up from Georgetown. And, assembled in the first rows, Marable’s family members — including Leith Mullings; his sister, Madonna; and his three children and two stepchildren — provided, in their graciousness and modesty, a key to the man that was beyond any text.

After an opening benediction from University Chaplain Jewelnel Davis, Madonna Marable stood and sang “Amazing Grace,” a request from her late brother. Then, from the podium, came an extraordinary outpouring of appreciation. President Lee C. Bollinger called Marable “an academic hero who will stand forever.” Provost Claude Steele spoke of Marable’s “old-fashioned hard work and fearless inquisitiveness.” Eric Foner praised him as “the consummate public intellectual.” To Farah Jasmine Griffin, professor of English and comparative literature and African American studies at Columbia, Marable was a “sheer force of nature” who chronicled better than anyone the “epic, painful, but beautiful struggle for freedom.” Dyson, who had defended Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention in a debate with Amiri Baraka on Democracy Now!, called his friend “a disciplined scholar” and “a great man.” For Russell Rickford, Marable was “America’s postcolonial Du Bois.” And Zaheer Ali repeated his teacher’s sweet refrain: “I’ve got the best job in the world; I get to teach Black freedom every day.”

One of Marable’s children, Sojourner Marable Grimmett, then got up with her brothers and sisters. Her voice trembling, “Soji,” as her father called her, made a final appeal to the audience. “Our dad was not only amazing in his work but truly amazing as a father,” she said. “That’s the type of legacy that we want to leave. Be amazing.”

At the end, everyone was asked to stand. Madonna Marable, accompanied by pianist Courtney Bryan ’09GSAS, sang the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

The voices rose, and for a moment, it seemed, Earth and Heaven did ring.

“Dear Honorable United States Attorney Eric Holder,” began the letter that Alvin Sykes had mailed, coincidentally, on Manning Marable’s birthday.

Sykes, a compulsive reader who had educated himself on civil rights law in the public library, was the man behind the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act, legislation named for the young Black teenager from Chicago who was tortured and murdered in Mississippi in August 1955 for reportedly saying, “Hey, baby” to a white woman. In 2005, Sykes convinced U.S. senator Jim Talent, Republican of Missouri, to introduce a bill that would create a unit inside the Justice Department to investigate old crimes from the civil rights era. In 2008, President George W. Bush signed the bill into law.

Now, having read Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Sykes was following the playbook by which he got the Till case reopened in 2004. In his letter to Holder, he outlined the technical legal grounds for reopening the case of Malcolm X.

On May 17, four days after mailing the letter, Sykes drove 65 miles to Topeka, Kansas. In the car beside him was his friend, Kansas state senator David Haley, who is the nephew of Alex Haley. The two men were heading to an event at the Topeka Ramada commemorating the anniversary of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. The keynote speaker was Eric Holder.

After the attorney general’s address, Sykes sought out Holder, and the two men shook hands. According to Sykes, Holder, without any prompting, told him that he had personally received Sykes’s letter and that the DOJ was reviewing it. Sykes left Topeka feeling hopeful.

“I expect it will take a while,” Sykes said in June. “Months at least, because of the potential involvement of state law enforcement in addition to the FBI. But overall, I feel confident that there will be an investigation.”

You might call it living history.