Juan González, sixty-five, a columnist for the New York Daily News, zooms up the Avenue of the Americas in his brown Subaru hatchback toward Rockefeller Center. He just wrapped a broadcast of Democracy Now!, the independent news program that he’s co-hosted with journalist Amy Goodman since 1996. Today’s show ran long with a segment on the Obama administration’s crackdown on whistleblowers, and the columnist had to rush out. It’s ten in the morning, and González is staring down the barrel of 3:00 p.m.

“I’m always working on a bunch of different stories at the same time,” he says, scanning the street for a parking spot. “But the problem is, the column is always due every Tuesday and Thursday” — he gives a half laugh from the throat, the amused aspiration with which he punctuates truths, large and small — “whether I’m ready or not. The space is there, and I have to figure out what’s ready to write.”

It’s a Thursday, mid-April. Earlier, Democracy Now! covered two big stories: the Boston Marathon bombing three days earlier (still no suspects, despite what CNN and the New York Post might have indicated) and an explosion at a fertilizer plant in Texas that killed fifteen people and injured two hundred. But for González ’68CC, his mind buzzing with government data, City Council motions, House bills, labor contracts, property law, budget figures, hospital records, and tipster’s notes, the news is everywhere.

Take today: González is playing with three ideas for his pending column. There’s the Hudson Yards West Side redevelopment deal (“The city promised, when Hudson Yards was approved in 2005, that it would build thousands of new housing units in the area, and that 28 percent would be affordable housing. It’s now eight years later, and I’m trying to find out what actually happened”); a dustup in Brooklyn in which parents from three public schools that share a building with a freshly renovated charter school claim that the Department of Education failed to give their facilities equal improvements; and the city’s proposed $144 million contract with Verizon to maintain its 911 system, even though Verizon has yet to pay the $59 million in damages sought by the city over delays in the original upgrade.

“Investigations in the press have dwindled,” says González, a two-time George Polk Award winner and a News columnist since 1987. “They cost money and take more time to prepare, which is an investment that most commercial media no longer feel they have to make.”

González began his career in 1978 at the Philadelphia Daily News. His early pieces were dispatches from Puerto Rican and black neighborhoods, human stories told in straight, unsentimental prose with a moral edge. He portrayed the victims of crime, fire, and negligent landlords, profiled real-estate speculators, exposed fishy land deals and education scandals, produced a major series on cancer rates near industrial sites, and, later, covered City Hall.

“I’ve always been interested in digging deeper into stories, and have gradually zeroed in on land development and government contracting, areas that nobody covers. I’ve gotten away from pack journalism. Right now, everybody’s on the Boston bombing, so how many new things can you come up with? I’d rather go to where nobody else is paying attention.”

González nabs a parking space. He gets out of the car and walks to a curbside vendor and buys coffee and a jelly donut. Cup in one hand, paper bag in the other, the columnist crosses Sixth Avenue, shambles into the old Sperry-Rand Building, and rides the elevator up to the Daily News.

A brief timeline of events illuminating the passion of Juan González begins, aptly, with a headline:

THE SPIRIT OF WAR PERVADES THE

BREASTS OF ALL AMERICANS

Patriotic Citizens Advocate Recourse to Arms to

Wreak Vengeance Upon Spain for the Cruel and

Cowardly Destruction of the Maine

1898: Bolstered by public froth whipped up by the Hearst and Pulitzer empires over alleged Spanish atrocities, the US helps the Cuban and Filipino militaries defeat Spain in the Spanish-American War, gaining control of the Philippines, Guam, Cuba, and the fertile Caribbean jewel of Puerto Rico. After four hundred years of Spanish rule, many Puerto Ricans welcome the English-speaking vanquishers, believing them the heralds of Puerto Rican self-determination.

1917: The US, having retained Puerto Rico and opened her to US sugar interests, passes the Jones Act, which preserves US authority over Puerto Rican political and economic life, and makes all Puerto Ricans US citizens. Puerto Ricans are now eligible for conscription, and about 18,000 serve in World War I.

1937: After years of severe economic distress, Puerto Rico roils with anti-US feeling. On March 21, Nationalists march on the southern city of Ponce to commemorate the end of slavery on the island. The demonstrators are met by the police, who fire into the crowd. Nineteen people are killed. It’s the worst massacre in Puerto Rican history.

1947: Juan González is born in Ponce. When he is four months old, his family, in a wave of US-planned emigration meant to ease political and economic tensions on the island, moves to the mainland US. New York City. East Harlem. El Barrio.

That is where González’s own story begins.

González steps off the elevator with his donut and coffee and hatful of stories and enters the vast, open office of the Daily News: rows of desks and computers, headphoned workers glued to their terminals, Samsung flat screens (CNN, ESPN) screwed to every cream-painted support beam. González steps into a small private office.

He sits at his desk in a reclining chair, picks up the phone, leaves a message for a Brooklyn parent. “This is Juan González of the Daily News,” he says, with no trace of expectation that the name will produce a result. “I’m trying to do something for tomorrow’s paper. Please call me as soon as you can.” He hangs up, punches more numbers, and leans back with the receiver to his ear, his fingers tentacled around the mouthpiece. “They didn’t mention how big the hole is that the city is going to have,” he tells the source on the other line, “’cause, you know, the interest payment on bonds actually went up this year.” González speaks in a rich semi-nasal New Yorkese mixed with a scoop of asphalt. “Like I said, the ideal report puts it all in one place and counts all the money, but I’m concerned that my editors won’t want me to do another piece on how much money’s being sunk into Hudson Yards.” He makes more calls, spills some donut crumbs on his desk. “Councilwoman, how ya doin’? It’s Juan.” This for a longer-range story. He lowers his voice. “How is it possible for a charter-school network that works in an almost tyrannical manner with these students — that’s how they treat them in school — how is it possible for the schools to keep producing these incredible scores? It has to be that they’re pushing out all the kids that are gonna do bad, so that they can only have” — the half laugh — “kids that they know are going to produce good test scores.” After this, González calls back the parent for the fourth time in an hour. “Sorry to keep bothering you; it’s Juan González at the Daily News, I’m desperately trying to reach you …”

The family lived in a cold-water flat in a tenement on East 112th Street, in the Italian section of El Barrio. González’s mother was a seamstress and garment worker. His father, an alcoholic and barely literate, worked in a Bronx cafeteria and stressed education to his children with what González would later describe as “a frenzy that bordered on cruelty,” often involving a leather strap.

In 1956, the family moved to a housing project in East New York, Brooklyn. González attended Franklin K. Lane High School, where he was one of the few Puerto Ricans on the mostly white campus. His English teacher, Pauline Bonagura, convinced González’s parents to let him apply to a summer high-school program at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. “The summer of 1963, I went to Northwestern and studied journalism,” González says. “The following year, my senior year, I was the editor of the paper.”

This was no ordinary high-school newspaper. González’s staff included David Vidal, future foreign correspondent for the New York Times, and Stephen Handelman, future foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star.

“My guidance counselor, Judith Temple, told me, ‘Hey, you need to apply to Columbia.’ I didn’t even know what Columbia was. Certainly my parents didn’t. I applied to a bunch of colleges. Grinnell College in Iowa and Columbia offered me full scholarships. I wanted to go to Grinnell, but in my senior year of high school, my father died. He died of cancer. My mother didn’t want me to go all the way to Iowa. So I went to Columbia for my family. That turned out to be a good decision.”

González became the first in his family to go to college, and one of a handful of Latinos at Columbia. Well-liked but culturally alienated, he joined the Spectator as a sports reporter, and had the occasion to write a news story about a student-run tutoring program for needy families on the West Side. González fell in love with the program. He quit the Spectator and got involved in other local causes, including working with citizens in Manhattan Valley who were organizing against a gym that Columbia planned to build in Morningside Park. Some people objected to the idea of a private institution constructing a recreational facility in a public park in a poor neighborhood without giving equal access to the residents.

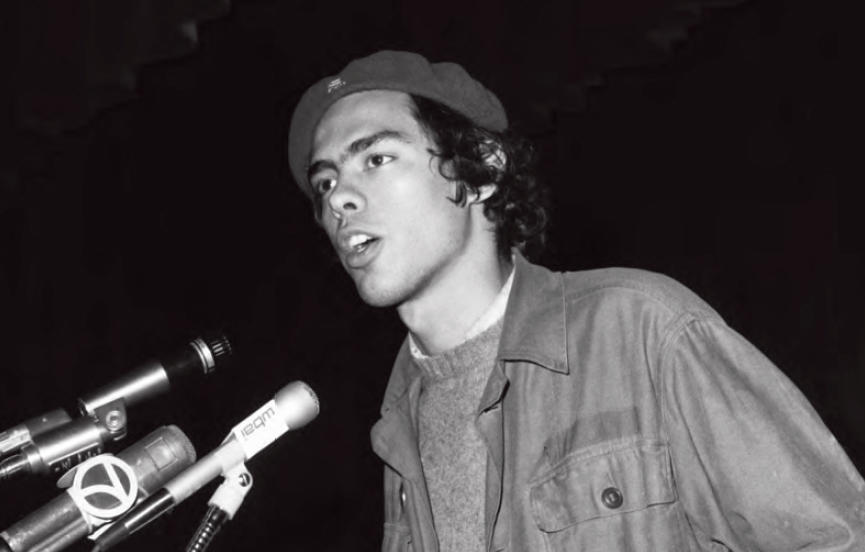

“In January ’68, I participated in a protest at the gym site,” says González. “A young African-American minister convinced a bunch of us students to join him in sitting in front of the bulldozers. We all got arrested. When the student strike broke out in April, I became involved.”

In the student protests against the gym and the University’s involvement in weapons research amid the US war in Vietnam, González occupied a Columbia-owned building on West 114th Street and was arrested a second time. Columbia suspended him. Decades would pass before he got his degree.

By the fall of ’68, González had joined Students for a Democratic Society, and the following spring he participated in a takeover of Mathematics Hall. But in 1969, it seemed, most students just wanted to go to class. González was arrested and spent thirty days in jail.

The stay did not reform him. As soon as he got out, he took his activism to where it was needed most — a dozen blocks east of campus, and a thousand worlds away.

González hangs up the phone, bites into his donut. It’s past 11:00. Ready or not, he steps out into the newsroom and walks over to Jill Coffey, the morning editor at the city desk.

“Hey, Juan!”

“Hey, how’s it going?”

González sits beside Coffey, who asks González what he’s going to write. “I have no idea yet,” González says. He mentions the Texas explosion and pitches a piece on workplace deaths.

“Yes, I like that,” says Coffey.

“The other possibility, more local, is another Success charter thing.”

After González’s spiel, Coffey says, “I always like the charter-school stories, because I feel that they affect a lot of people. To me, that’s the one.”

The summer of ’69: not your hippies-in-the-mud-LSD-rock-festival ’69, but a health/education/housing crisis in El Barrio that drove twenty-one-year-old González and a group of young, educated, media-savvy Puerto Rican nationalists to form the Young Lords. Not a street gang, as in their Chicago antecedents, but a multiethnic squad of community-focused, Black Panther–influenced revolutionaries, young men and women in purple berets with pins that said “Tengo Puerto Rico en Mi Corazón,” who over the next three years pulled off a string of spectacular direct-action gambits. They burned garbage on Third Avenue to protest a chronic lack of sanitation services, procured urine-testing kits to detect lead levels in children in tenements (bringing national attention to lead poisoning), obtained TB screening equipment and training from supportive doctors and then politely commandeered a city x-ray truck to perform follow-up chest x-rays, reentered a local church (where they’d previously been assaulted by the police) and turned the structure, briefly, into a community center with a children’s free-breakfast program. Later, they slipped into the decrepit city-owned Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx at 3:00 a.m., took over a wing, and, with willing medical staff, turned it, also briefly, into the People’s Hospital, providing testing for anemia, TB, and lead poisoning, as well as drug treatment for addicts.

“From July 1969 to 1971, the Young Lords developed a fascinating and compelling way to frame the issues and act on them,” says Frances Negrón-Muntaner, director of Columbia’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race. “The community didn’t have access to the resources necessary to create well-being, and the Young Lords dramatized that by specializing in what you could call the victimless kidnapping of buildings, calling attention to resources that were available but not being offered to the community.

“They were superheroes in a way, and no one ever got hurt, which was a key part of their strategy,” she says. “Every target they selected had to do with producing a healthy Puerto Rican political and physical body that could fully participate in the city. Sometimes they were arrested, but they were never tried. And if they were arrested, the people running the institution would drop the charges and say, ‘They are right!’”

Ray Suarez, senior correspondent for the PBS NewsHour, has known González for twenty-five years. The two met through the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, which González cofounded in 1984.

“Juan has been a friend of the little guy throughout his career, crusading for powerless, voiceless people,” says Suarez. “And all he’s doing through journalism is what he was doing through activism in the Young Lords.”

In 1972, the group, aiming to organize Puerto Rican labor, changed its name to the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization. Members moved to cities where Puerto Ricans worked in industry. González got a job at the L. W. Foster Sportswear factory in Philadelphia. In 1973, the year of the last major national garment workers’ strike, he organized Foster’s five hundred employees. But as the reconfigured Lords became “increasingly extreme and Maoist,” González left the organization and got a job at a newspaper printing plant.

Late in 1978, he enrolled in a journalism course at Temple University. Two weeks in, the instructor, who was an editor at the Philadelphia Daily News, encouraged González to apply for a job at the paper. González did, and in December, the paper hired him as a clerk. By early 1979, González was a full-time reporter.

The charter-school story comes out Friday, and that morning González drives from his home in Inwood, where he lives with his wife and teenage daughter, to the Chelsea set of Democracy Now! Having started as a radio program on the five-station Pacifica network, Democracy Now! is currently broadcast over more than 1,100 media outlets worldwide.

González, in a gray suit, takes the elevator and exits into a spotless, sunny office that wraps around the entire floor, with the TV studio in the middle. The walls and shelves flash with plaques and trophies, including González’s Polk Awards.

The show starts at 8:00 a.m. Amy Goodman delivers the headlines (in Boston, one suspect in the marathon bombing is dead and another is at large; thirty-two people are dead in a suicide bombing in a Baghdad café; Venezuela is auditing votes in its election after calls for a recount). González then presents a segment on the trial in Guatemala of the former US-backed dictator Efraín Ríos Montt, who is being tried for crimes against humanity for the slaughter of Mayans during the military’s campaign against leftist guerrillas in 1982 and 1983. “Ríos Montt,” González tells the audience, “is the first head of state in the Americas to stand trial for genocide.”

With all eyes on Boston, an in-depth report on the trial of an ex-dictator in a small Latin American country might seem extraneous to a US audience. But as González has shown, foreign involvement can yield all sorts of unintended harvests.

When Frances Negrón-Muntaner arrived at Columbia in 2003, one of her tasks was to develop Latino Studies, including the Introduction to Latino Studies course. She had read González’s book Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America, which appeared in 2000, and felt it would give students a complex, accessible synthesis of the history behind Latino immigration and settlement.

“González came up with a gripping metaphor,” Negrón-Muntaner says. “When you use ‘harvest of empire’ to understand the Latino presence in the US, it provides an explanation to all who ask, ‘Why are there so many Latinos here?’ Harvest of Empire shows that this process has taken a very long time, and doesn’t fit the American-dream narrative of upward-mobility immigration. Though many of those who are immigrants come here for a better life, the larger social forces propelling this movement of people are part and parcel of American expansionism and intervention in those very countries that become producers of immigrants. People say, ‘They are aliens. They are foreigners. What are they doing here?’ But when you look at the conditions of the US state-and nation-building process, you realize they’re not foreign. They’re not alien.”

Harvest of Empire is required reading in nearly two hundred colleges in the United States. The revised 2011 edition covers the current immigration debate and was made into a documentary that has played in a dozen US cities since February.

After fifteen years in Philadelphia, González returned to New York in 1987. He had a job waiting at the Village Voice, but when the Daily News offered him a column, with better pay, González grabbed it.

These were grim years for race relations. González covered the Crown Heights riots, the LA riots, the Washington Heights riots. He emerged as the leader of the 1991 Daily News strike, chronicled the Giuliani years, won the Polk in 1998 for his “street-savvy, unflinching columns,” and, a decade later, uncovered the largest fraud against government in New York City history: a taxpayer boondoggle in the Bloomberg administration’s CityTime project to computerize the municipal payroll, in which CityTime consultants ripped off the city for $740 million. The stories led to indictments of consultants and the resignation of the city’s payroll director — and earned González his second Polk.

But González might be better known as the journalist who, a month after the 9/11 attacks, wrote columns on the dangerous levels of contaminants around Ground Zero.

“Everyone was interested just in returning the city to normal, and there was a big push to get people back to working in the area,” González says. “Through my environmental contacts, I got ahold of results from tests that the EPA and the city had been doing that showed there was much more contamination than people realized.”

There was backlash against the paper from the Giuliani administration and Christine Todd Whitman, the head of the EPA. They said González was exaggerating. Whitman contacted the Daily News and was allowed to write an op-ed piece countering González’s claims.

“Some of the editors started quashing my columns,” says González. “They killed two of them and relegated the others to the back pages. So I went to Ed Kosner, the editor in chief, and said, ‘Ed, why are you holding up my columns?’ And he said, ‘Well, the EPA says the stuff that you’re writing isn’t accurate, and so does the Giuliani administration, and besides, the Times isn’t writing anything about it.’ And I said, ‘Since when do we decide what we’re going to write based on what the Times decides to write? You have to trust my reporting.’ So we went back and forth, and I finally said, ‘Ed, you don’t know me well. And I don’t know you well because you’ve only been here a couple of years. So here’s what I’m going to do: I’m going to keep writing on this topic. I think it’s important, and when a lot of people start getting sick ten or fifteen years down the line, I don’t want it to be on my conscience that I didn’t do what I needed to do as a reporter.’”

Five years later, as people started getting sick, the paper, under different editors, ran editorials exposing the problem. For this, the Daily News won a Pulitzer Prize.

“Early on, I developed a sense about the unjust treatment of people,” González says in his office, when asked what motivates his work. “Even how my own family was treated.”

It’s a Wednesday morning in June. González is dressed in a pale-orange polo shirt and turtle-green sports jacket. This morning’s column reports that the city’s new $88 million 911 dispatch system has crashed four times in its first three days.

“When I was sixteen,” González says, “my father started having pains in his neck. He kept going to the doctor, who told him repeatedly it was nothing. Finally, the doctor said he needed a procedure, but it was August and the doctor was going on vacation and said he’d do the procedure when he came back. The pain developed into a tumor that grew very rapidly. When the doctor returned, he realized it was cancer, and sent my father to Sloan-Kettering. In those days, a Puerto Rican walking into Sloan-Kettering” — the half laugh — “was more like a curiosity.”

González’s father had surgery the next day, and died. The doctors claimed the tumor had gone too close to the brain. When they tried to remove it, it caused a brain hemorrhage.

“I really felt that my father was not treated the way other patients would have been,” González says. “So the sense that people who don’t have any income or wealth are treated unjustly has always been with me. After the Young Lords, I decided that I wanted to use journalism as a way to right wrongs.”

This morning, González has two pots boiling for his next column. One involves a large, quota-driven increase in inspections and fines against small businesses in all boroughs except Manhattan. The other concerns a curious pattern of disciplinary actions in a powerful, high-performing K–6 charter-school network, a story that González has been developing for more than a year.

“It looks very much to me,” he says, opening a yellow folder on his desk, “that they held this student back because he was going to ruin their test scores.” González thumbs through some papers, and a glint of delight enters his voice: the thrill of the sleuth closing in. “If I’m able to show that this has been a sophisticated operation of rigging test scores,” he says, “it’s gonna blow this thing completely out of the water.”

Photos by Ashok Sinha '99SEAS.