Jenji Kohan ’91CC is a rare bird among television showrunners: blue-haired and female, a punkish Jewish earth mother with a darkly comic vision so basic to her nature that the goblin of political correctness shrinks in her presence. As a writer, she is fearless. She will go there, and keep going.

“I find the funny in everything, especially the inappropriate,” she says. “Maybe it’s my survival technique.”

Kohan’s company, Tilted Productions, is based in central Los Angeles, in a Spanish Colonial–style building of pink stucco, arched windows, and iron grillwork. Built in 1926 as the Masque Playhouse, it was later renamed the Hayworth Theatre (legend has it that Rita Hayworth’s father once ran a dance studio there). Kohan bought the place in 2013. Now, after a major renovation, it’s a clean, spare, sunny, feng shui triumph of orderly space and calming energy, with long hallways and private writing rooms, a large open kitchen and dining area, and even a children’s playroom filled with brightly colored educational toys. This is where Orange Is the New Black, Kohan’s award-winning women’s-prison dramedy series, is conceived, discussed, mapped out, written, edited, and birthed.

With the latest season of Orange in the can, the building is quiet today, and Kohan is relaxed. Her private office exudes warmth and comfort, as does Kohan herself. Her hair is the vivid indigo of blue velvet. Her cat-eye glasses could have been teleported from a 1962 mahjong game. Objects on her desk attest to a fondness for thrift-shop flotsam and novelty doodads: two Magic 8 Balls, a Weeds condom, and a beanbag emblazoned with an unprintable four-letter word starting with the letter C.

Life wasn’t always this good. “I spent the first part of my life very frustrated, feeling patronized, and fighting injustice, and it doesn’t work when you’re young,” Kohan says, seated in an armchair with her feet tucked under her. “But that frustration turned into this.” This being the whole schmear: the hit shows, the peaceful office. “Whenever anyone told me I couldn’t do something, it pushed my buttons. Basically, I’m driven by vengeance.”

From early on, Kohan clashed with naysayers. In fifth grade, as a “strange, depressed, and chubby kid,” she circulated an anti-censorship petition after her play was canceled when a teacher objected to a scene in which an Asian character gives someone egg foo young.

Another time, she was suspended for saying to an administrator, “I’m sick of this bureaucratic bullshit” — a line that could have easily come from one of her child characters. She was hot on the scent of hypocrisy and found battles everywhere. “I did a lot of tilting at windmills,” she says. “It’s really hard to be a kid, because you have no power. You are written off.”

Not surprisingly, Kohan’s child characters are often the moral center of the damaged adult universe they inhabit. Her first show, Weeds, was a half-hour Showtime comedy about a widowed suburban California mom (played by Mary-Louise Parker) who becomes a pot dealer to maintain a comfy lifestyle for herself and her young, hypocrisy-sniffing sons. Noted for its crack writing, its warped humor, and Parker’s nuanced performance, Weeds ran from 2005 to 2012.

The show’s success led to a great leap in Kohan’s career, and for the television paradigm generally: Kohan was one of the first showrunners to sign with the streaming service Netflix, which, after hearing Kohan’s pitch for Orange Is the New Black, offered her the remarkable opportunity to make an entire thirteen-episode season up front. The season would be released all at once, and subscribers could stream it online. It was a new way not only to create television but also to consume it. Best of all, Netflix granted Kohan an unprecedented level of creative freedom.

Orange, now entering its fourth season, is loosely based on a memoir by Piper Kerman, a Smith College graduate from a patrician family who served thirteen months in the federal correctional institution in Danbury, Connecticut, on drug-related charges. Critics regard Orange as one of the best and most important shows on television.

“The characters Jenji creates are dark, twisted, funny, and startlingly honest,” wrote Shonda Rhimes, creator of Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal, in Time magazine, which in 2014 named Kohan one of its hundred most influential people. “She’s turned criminals into women we know, women we care about, women we root for.” Rhimes, who is Black, also praised the “breathtaking riot of color and sexual orientation” of Orange, crediting Kohan with “creating characters of all backgrounds who are three-dimensional, flawed, and sometimes unpleasant, but always human.”

Kohan pleads guilty. “I love flawed people,” she says. “I love the damage in these characters. It’s so human and so relatable. People spend so much time trying to hide it and cover it, and no one’s succeeding. I love embracing it. I love mess. I love gray areas. I want to live in the gray areas.”

EXT. A HOUSE IN BEVERLY HILLS – 1982

From within, we hear sounds of PARENTAL EDICTS: “Shut off the TV! Go be social! Go do something productive!”

INT. SAME HOUSE – CONTINUOUS

As THE CAMERA pushes through the rooms, we see a crammed bookcase, a menorah, a shelf crowded with Emmy statuettes.

THE CAMERA arrives in the TV room, where a TEENAGE GIRL is curled on a sofa, watching Cheers.

PARENTAL VOICE

(from next room)

Go learn to play tennis!

Jenji Kohan grew up in Beverly Hills with her older twin brothers, David and Jono, and her parents, Rhea and Buz. Rhea was a novelist, and Buz was an award-winning TV writer who worked on hundreds of network specials and series, including The Carol Burnett Show and the Academy Awards. But the most sacred objects in the house were not his collection of Emmys — they were books. The kids were encouraged to be readers, not viewers. And not writers. Doctors and lawyers, preferably. Something secure.

Kohan was an erratic student, but she tested well. After some unhappy years in an all-girls private school, which had cutthroat social divisions, she transferred to the coeducational wilderness of Beverly Hills High.

“It was a fascinating culture,” she says. “Everyone was trying so hard to be sophisticated that there weren’t strict hierarchies. It was more like interest groups. And the parties were amazing: ‘So-and-So Productions Presents: Party at Larry’s Mom’s House.’” Kohan recalls John Hughes–caliber blowouts, the kind that end with a mannequin in the pool and a pizza on the turntable. UCLA football players were hired as security. “Once you got past them, it was like the rings of hell: friends of friends on the tennis courts, friends in the house, then really good friends in the room with the cocaine, because it was the eighties.”

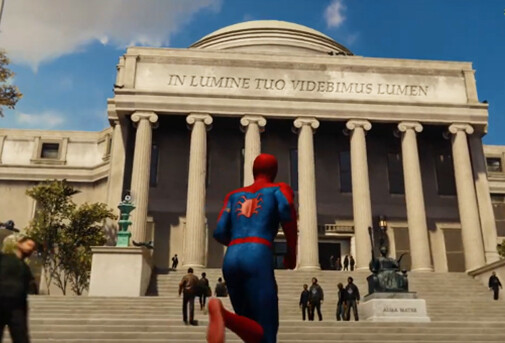

College was next. Kohan desperately wanted to go to New York, to Columbia. But there was a snag.

“Columbia wouldn’t let me in,” Kohan says. “So I started at Brandeis. Every few weeks I’d write to Columbia and say, ‘I think you made a mistake. Look! I just won a writing contest! I’m doing so well! Let me in, let me in, let me in.’ Then two weeks later: ‘Hi. Remember me? I just won $250. You should really let me in.’”

“Revenge is an act of passion; vengeance of justice,” wrote Samuel Johnson. “Injuries are revenged; crimes are avenged.”

That’s a helpful distinction, but clearly, Dr. Johnson never saw Orange Is the New Black. At the fictional Litchfield Prison in upstate New York, justice is so arbitrary, and passion so suppressed, that payback becomes less a legal or moral question and more a matter of style. The dynamics of retaliation enter every relationship in Orange.

Fortunately, Kohan also has great love for her characters, who in turn love each other — intensely, agonizingly, clumsily. And as they play their risky games, the show exacts its own reprisals against pieties of all sorts, while smartly skewering what Kohan calls the “out-of-control prison-industrial complex.”

“It’s not a secret that the work I do is also my soapbox,” she says. “Having a soapbox is a great privilege. However, it’s not effective if you’re scolding people. I always have an agenda, but my first job is to entertain and make the audience care about those characters and stories. You’ll never get your point across or move the needle or plant ideas unless people are invested. No one wants to be lectured. People watch TV for pleasure. It’s got to be fun. Prison is a dark, dark world, but I don’t think we’re being disingenuous by making it comedic. Humor is how you survive the darkness.”

Orange is essentially a comedy. Its snappy “Private Benjamin goes to jail” hook got the show past the gates, where it morphed into a human mosaic of faces and figures and sexualities unlike anything on television. (“Piper was my Trojan horse,” Kohan has said, meaning that she needed a pretty white lead to sell the show, and could not have sold it on the “fascinating tales of Black women, and Latina women, and old women, and criminals.”) Equally striking is the show’s ability to stay emotionally trenchant even as it deploys gross-out gags and takes sex to places several light years from family hour. “When we go dark, we go dark; when we go funny, we can get big sometimes,” Kohan says. “But I think both are more powerful when you juxtapose them — slam comedy right up against tragedy.”

Though Kohan considers herself an entertainer, and leaves activism to people “who are far more capable and organized,” she takes pride in the show’s influence on the discourse. “I think Orange has helped bring attention to prison reform, and we’ve opened discussions about the portrayal on TV of all sorts of bodies,” she says. “People are talking about things they weren’t talking about before. But I didn’t set out saying, ‘I’m going to change the face of television.’ It was just the natural extension of what I wanted to do: make a great show with people I wanted to watch.”

INT. WELFARE HOTEL – NEW YORK, 1990

A room inside a hotel on W. 110th Street. PAN to show: roaches crawling over a kitchen counter; dead roaches on a hot plate; half-empty containers of hot-and-sour soup; a stack of books, with titles by Anthony Trollope, Homer, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and John Cheever.

THE CAMERA reaches the couch, where a YOUNG WOMAN is watching her favorite TV show — The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, a half-hour magical-realism-inflected comedy-drama about the personal and professional life of a thirty-something divorced woman in New York, played by Blair Brown.

We hear SIRENS and SHOUTS out the window. The young woman is too engrossed in the show to notice.

Kohan transferred to Columbia halfway through her sophomore year. Her academic tastes were eclectic: she took classes on shamanism, film editing, and physics for poets. (According to one former classmate, she used her musings on an Elvis-bust lamp to kick off a paper on Locke and Hume, and got an A.) She had a concentration in English but didn’t declare a major. She just wanted to do the Core and get a liberal-arts education and be in New York. She was young and broke in the big, wild city. She felt free.

In her senior year she didn’t get campus housing and moved into a welfare hotel. It was all part of the adventure. Off campus, she got a different education. “I had a Japanese sugar daddy,” she says with a laugh. “But it was mostly chaste.” On weekends, she’d take long walks downtown, ending at Franklin Furnace, a performance-art space in Tribeca. As the intern, Kohan helped set up shows (“I was told I had no visual sense; apparently, I made very ugly fliers”). She was a devotee of spoken-word performance, and caught shows around town by artists like Eric Bogosian, Spalding Gray, and Laurie Anderson ’69BC, ’72SOA. She dreamed of sitting on a stool in an empty space, holding an audience rapt with her own tales. But in truth, she wasn’t comfortable onstage. She was too blinky, she felt. Too nasal.

She would have to write, then. After college, she returned to Los Angeles and picked up odd jobs. She worked in a juice bar in Venice and a video store on Sunset, and wrote restaurant reviews for the Los Angeles Reader (“they didn’t have a budget to send me to restaurants, so whoever was nice to me on the phone got a good review”). One day, her boyfriend told her about his best friend from camp, who was a writer. This friend, he said, was having success in television.

Success in television. The words raised Kohan’s competitive hairs. She’d written short fiction, but TV, too, was in her DNA. Maybe, then, she should give TV a shot.

That’s when the boyfriend uttered his fateful opinion.

“He told me I had a better chance of being elected to Congress than I did getting on the staff of a show,” Kohan says, winding up to her signature one-liner. “My whole career is ‘Fuck you, David Gershwin’ — er, Schmavid Schmershwin.”

Kohan’s buttons were pushed. Missiles stirred in their silos. Schmershwin had unleashed Schmarmageddon. Kohan quit her jobs and moved to Santa Cruz to stay with a friend who was going to medical school. There, in the friend’s “shitty apartment,” she watched tapes of Roseanne and Seinfeld and wrote spec scripts.

She returned to LA with a stack of scripts and got her ex-sister-in-law’s father to pass them to an agent who worked in the same building (the handoff occurred, naturally, in the elevator). Kohan had always known that if she pursued television, she’d have to be resourceful. “My parents’ philosophy was, ‘You’ve got to make it on your own.’ We had support, we had education, but it was not like, ‘Give my kids this job.’ I was supposed to be a lawyer or a well-heeled housewife, and my brother David was supposed to be a doctor, even though he can’t stand the sight of blood.” (David Kohan went on to co-create the NBC show Will & Grace.)

The agent was receptive, and soon Kohan, at twenty-two, joined the staff of the NBC sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. She remembers a dysfunctional, quarrelsome writers’ room — a “rough entrance” into show biz. Her next job was on Friends, where she argued with her older bosses for the inclusion of more authentic details about the lives of twenty-somethings. She was fired after thirteen episodes. Distraught, she escaped to the Himalayas to figure out her life. There, between hikes, she couldn’t help writing a spec script for Frasier. She took it as a sign that she wasn’t done with television.

Meanwhile, Tracey Ullman, the protean performer and writer, had gotten her hands on one of Kohan’s scripts. Ullman hired Kohan to work on the staff of HBO’s Tracey Takes On ... Kohan was part of the producing team that won the 1997 Emmy for outstanding variety, music, or comedy series.

“Tracey Ullman was a huge turning point for me,” Kohan says. “It was so healing, because she ran a sane and wonderful room. She gave everything a shot and set an incredible example. She packed the room with old-school heavy hitters, and then we would go off and come back for one serious day of work per week. She had a wonderful family life and did everything right, and she’s just a stellar example and talent. My time with her was invaluable. I was the baby in the room, and they were lovely to me. I’ll always be grateful to Tracey.”

Kohan spent three years with Ullman and would later heed the lessons, implementing a “no-assholes” policy in her own writers’ room and prioritizing her family. She and her husband, Christopher Noxon, a journalist and author, have three children, ages ten, fourteen, and sixteen. Kohan is a hands-on mother (“I didn’t have kids for other people to raise”) and exerts a similar influence at work. “I’m definitely a mother hen,” she says. “Tough love, and a need to do a million things at once. I’ve worked a lot and really learned over time what I wanted my work life to be like. So we have fairly sane hours. I’m usually home for dinner. I think it can all be accomplished if you’re organized.”

INT. WRITERS’ ROOM – DAY

A long table in a sunny room. Jars of colored markers on the table. The front wall is covered with photos of characters from Orange Is the New Black. There’s the fish out of water PIPER (played by Taylor Schilling); the Shakespeare-quoting savant Suzanne “CRAZY EYES” Warren (Uzo Aduba, who has won two Emmys for the role); the hard-bitten prison-kitchen empress “RED” (Kate Mulgrew); the transgender hairdresser SOPHIA BURSET (Laverne Cox); the burly, tank-top-clad BIG BOO (Lea DeLaria); the young, dreamy pen-and-pad artist DAYA DIAZ (Dascha Polanco); and dozens more, including a new inmate, JUDY KING, a tax-evading TV cooking-show host played by Molly Dodd star Blair Brown. (The season-three cast won the 2015 Screen Actors Guild Award for best ensemble in a comedy.)

ANOTHER ANGLE: We see the Orange creative team, many of them women. The team is seated around the table, tossing out ideas.

KOHAN (v.o.)

We have a lot of women on the show and on our crew, and behind the scenes at our company. And they’re all talented. It’s always about talent. Talent overrides gender for me. It’s hard enough to find a good writer, so I don’t care what’s dangling. If you can find talent with tits, terrific.

“Revenge,” wrote the philosopher Robert Nozick ’59CC, “involves a particular emotional tone — pleasure in the suffering of another.” Nozick argued that vengeance (he used the word “retribution”), by contrast, “need involve no emotional tone, or involves another one, namely, pleasure at justice being done.” But Nozick admitted that the two concepts often overlap. “I do not deny that there can be mixed cases, or that people can be moved by mixed motives.”

Such are the gray areas where Kohan likes to live.

Then there’s the wisdom of the philosopher Frank Sinatra. “The best revenge,” said the great showman, “is massive success.”

Kohan seems to be an adherent of the Sinatra school. And like Ol’ Blue Eyes, she can certainly be said to have done it Her Way.

It hasn’t been easy. She’d written seventeen pilots before she scored with Weeds. She knows, too, what it’s like to be a minority in the room. “There’s a way that men network that women don’t, and it’s been very good for them,” she says. The result, she suggests, is that women, vying for limited spots, have tended to view each other as competition, and been reluctant to offer help. “I love to help, and I call for help,” Kohan says. “Communication among women is changing, and as that happens I think there will be an explosion.”

But Kohan isn’t a finger-pointer. She looks at a system the way she looks at a joke: either it works or it doesn’t.

“I just think the business has been incredibly stupid and shortsighted in not acknowledging that the majority of the audience is female,” she says. “I don’t think it’s necessarily intentional — I don’t think there’s a cabal of men saying, ‘Let’s keep women out.’ I deeply understand tribalism and wanting to be surrounded by what’s comfortable. But sometimes you have to force yourself out of that bubble and realize that there’s stuff to talk about with people who aren’t like you. You have to get over your bias. Once you do that, you’ll find that comfort with others.”

She could easily be talking about the women in Orange, for whom tribalism is a fundamental matter of self-preservation. Much of the drama concerns people’s struggles to break away, to cross boundaries, to seek acceptance, at the hazard of physical or emotional violence. Where are they going? Where will they end up?

Kohan is tightlipped about the new season (release date: June 17), for obvious reasons. “I’m very proud of it, and very excited,” she says. “It’s going to be big.”

Coming from Kohan, that’s a potent promise. Her baseline is high. But whatever she’s got in store, it will be sure to amuse and offend, inspire and enrage, stroke and poke. When it comes to her work, Kohan, as the phrase goes, takes no prisoners.

“This is my fun and my entertainment, too,” she says. “I’ve been given this opportunity, and I’m not going to pull my punches. I’ve worked too hard to get here, and this is where I want to be, and I’m not afraid.”