"She’s acting out desires. She represents what people want to see, and it’s upsetting, because they don’t exactly know what to do with it."

— Cultural theorist Sylvère Lotringer

Baghdad, 2004. An explosive ordnance robot rolls along a dusty city street toward a pile of white burlap sacks. Soldiers, American, leap from armored vehicles, cradling their M16s. They must evacuate the women, children, and old men, who could be killed or maimed if they don’t move faster. Cars race past, horns blaring. Soldiers yell and push. Closer to the kill zone, three members of the Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) unit — Thompson, Eldridge, and Sanborn — huddle around a monitor, watching the feed from the robot’s camera. Sanborn controls the robot by moving small joysticks on a board. The robot’s pincer grasps a snatch of burlap and slowly parts the material, revealing the head of a dark gray bomb. “Hello, mama,” Sanborn says.

The team calls the robot back and hitches a small wagon to it with a payload of charges to detonate the device. The robot goes off again on its miniature-tanklike tread. As it bumps over a pile of rocks, the rickety little wagon falls apart. Shit. Now Thompson has to go down there and lay the charges himself. Thompson, who has the heroic jawline of an aging quarterback, is the leader, the guy who wears the 100-pound steel-plated bomb suit and the helmet and gets up close to the deadly thing and touches it. His buddies zip him up, set his helmet firm, and wish him well.

Thompson walks toward the pile, breathing heavily in the desert heat. There are sand-colored buildings, burnt-out cars.

Above, a shuddering helicopter crosses the sun. Eldridge and Sanborn cover Thompson from a distance, scanning the windows and storefronts through the scopes of their rifles. Thompson reaches the bags, kneels before them. Slowly, delicately, he lays the charges. Then he straightens up, turns, and begins walking back toward Sanborn and Eldridge and the Humvee.

Suddenly, Eldridge sees something. He looks through his scope: there, across the road, in front of a butcher’s shop, amid the skinned animals strung up in the heat, is a man in a white smock, and he is holding something. A switch flips inside Eldridge: “Sanborn!” he yells, and runs toward the shop. “Butcher shop, two o’clock, dude has a phone!” The man in the smock waves, smiles, the picture of innocence, but Eldridge is locked in. “Drop the phone!” he shouts, sprinting now. Sanborn, in pursuit, calls, “Burn him, Eldridge! Burn him!” But there’s no clear shot, and the man pushes the buttons, and we then see Thompson running in his bulky suit, still within the zone, and the ground behind him erupts in a gush of pewter gray, and you cover your eyes as Thompson, our quarterback, is blown forward in slow motion, and the earth spews skyward like a volcano.

You must be dreaming, because when you open your eyes, you find yourself seated at a table in the brick patio lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel. Birds chirp. Across from you is a woman, tall and slender, wearing a black leather jacket, blue jeans, and a small crucifix around her neck. She has long chestnut hair and expressive hands. “The light is so beautiful these days because we just had this giant windstorm,” she says, a poet of extreme conditions. “The clarity — it’s just so magnificent.”

Yes. Magnificent. Sunlight seeps through a canopy of blade-shaped leaves. There are pink stucco walls, and clay pots of luminous pink and purple bougainvillea.

The woman is Kathryn Bigelow, the director of The Hurt Locker, a psychological thriller involving a unit of U.S. Army bomb technicians in Iraq and one of the most acclaimed movies of 2009. Having just consumed all eight of Bigelow’s feature films in 72 hours, your brain is revved up for blasts, killer waves, hunks of metal, erotic obsession, blood, guns, burning rubber. Bigelow has long been one of our most daring and original filmmakers, and The Hurt Locker is the most potent cocktail yet of her vast visual powers and her lasting formal and thematic concerns. The movie examines, in a war setting, the attraction to physical risk, which, for the freewheeling, industrial-metal-listening bomb dismantler Staff Sergeant William James (played by Jeremy Renner), has a chilling intimacy: “Hello, baby,” James murmurs, brushing dirt from a plump, leaden bomb that he’s uncovered in an empty square. Later, after snipping more wires, and coming within a whisker of his life, he retires to his Humvee and lights a cigarette: the Marlboro Man of Mesopotamia. “That was good,” he says.

It’s a classic shot from the Bigelow canon, where desire and death often converge, and heroes are seduced by things that might kill them. The Hurt Locker ups the ante by employing an immersive visual scheme — multiple Super 16 millimeter cameras, hair-trigger point-of-view shots, a 360-degree field of vision — that implicates the viewer in the action.

“It’s an experiential form of filmmaking,” Bigelow says between sips of fruit juice. “You’re inviting the audience to walk in those soldiers’ shoes, to look at the conflict through those soldiers’ eyes.”

As she speaks, you recall standing outside a UN compound, within range of a carload of bombs that the unit has come to defuse. You are surrounded by apartment buildings, from whose balconies and windows Iraqi men gaze impassively, unreadable as the wind. Your vision whips from one potential trouble spot to the next, until it locks onto a man on a rooftop: he is aiming a small video camera directly at you. It’s as terrifying as it is absurd. Should you kill him? Who is he? And who are you?

“The movie is looking at the humanity of the conflict, and the dehumanizing, soul-numbing rigors of war,” Bigelow says. “There are soldiers who are either just numb, or who are so switched-on that they’re capable of anything.”

Switched-on. It suggests a high-tech adrenaline rush: a click, a spark, wattage to the blood. You then recall that The Hurt Locker begins with a quote from the New York Times war correspondent Chris Hedges: The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug.

“What switches you on?” you say. “As a filmmaker, what’s the drug?”

Bigelow gives a sporting laugh. “That’s tough,” she says, but she thinks about it for a moment. Then, with care: “I suppose it would be the opportunity to provide a text that is provocative.”

That opportunity arose in 2004, when the journalist Mark Boal was embedded for two weeks with an EOD unit in Iraq. Upon his return, Boal, who had worked previously with Bigelow, related his Iraq experiences to her, and “we both thought it would make a great entry point for a film,” Bigelow says. Boal wrote the script, and when Bigelow read it, “I knew it was tremendous. No one had realized that the epicenter of the war was squarely on the shoulders of the EOD and that they were the war, basically. It was very timely, and I wanted it to be as expedient as possible.” The movie became a financial reality, she says, when Nicolas Chartier of Voltage Pictures offered to raise the money. “I think this was a brave and creative choice on his part given that I didn’t want to cast any major movie stars in the leads in order to preserve the naturalistic tone of the material, and to heighten the suspense.” Bigelow also wanted to shoot in the Middle East, “as close to the war zone as possible.”

To that end, she scouted Morocco. “Bomb disarmament protocol requires a 100- to 300-meter containment, so the sets were naturally quite large,” she says. “Morocco could not provide that breadth of set, architecturally speaking — it looked like North Africa, not the Middle East. Baghdad, where the story was set, was a war zone and off limits as a film location, so we scouted Jordan, where the architecture was virtually a perfect match. The Jordanians were very receptive.”

Bigelow now had a theater of operations — the capital city of Amman — that could pass convincingly for the war-rocked nation next door. As a bonus, the Jordanian military hardware — the Humvees, tanks, and armored personnel carriers — was American-made, and Jordan was also home to a community of Iraqi actors who had been displaced by the war. These resources, and the raw depiction of urban warfare, inject The Hurt Locker with the authenticity and immediacy of The Battle of Algiers.

It’s a sharp turn for Bigelow, most of whose work, like the brilliant vampire love story Near Dark (1987), and the visionary cyberpunk thriller Strange Days (1995), has been fiercely fictional.

“I’m almost more excited by reality in some ways,” Bigelow says. “Dealing with a conflict that’s real and ongoing provides the opportunity for the material to be topical and relevant. If you can cause people to think about that conflict as they walk out of the theater, then I think you’re really maximizing the potential of the medium.”

Bigelow’s mastery of that medium might be finally getting front-page attention (expect heavy Oscar action for The Hurt Locker this winter), but cinema hounds have been on the trail since her first feature, the art-house biker flick The Loveless, came out in 1982, starring leather-clad Willem Dafoe as the leader of a motorcycle gang that sojourns in a roadside town in the 1950s South. With its rebellious young bloods, simmering sexuality, and sherbet palette — the pinks and peaches of the women’s dresses, the lemon yellows and pistachio greens of the cars — it evokes Douglas Sirk, and inaugurates a succession of bold, genre-bending movies. These include Blue Steel (1989), about a female rookie cop who falls for a psychopath with a deadly fetish for her gun (“Death,” says the killer, “is the greatest kick of all”), and Point Break (1991), in which an FBI agent infiltrates a gang of bank-robbing surfers whose leader, a high priest of thrills, counsels, “If you want the ultimate, you gotta be willing to pay the ultimate price.”

Drawing inspiration from directors like Hitchcock, Peckinpah, and Fassbinder, Bigelow makes smart, violent, suspenseful, exquisitely photographed movies, shot through with grim wit and some of the most electrifying action sequences in the business: car and foot chases, shootouts, 100-foot walls of fire.

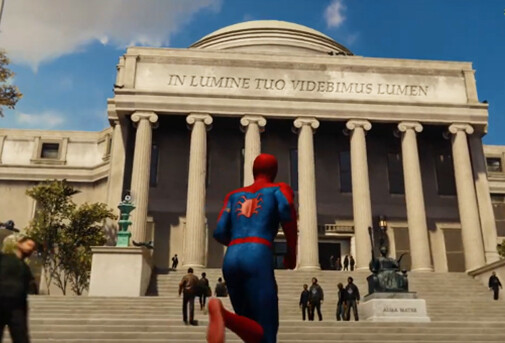

“There’s a maverick streak in her that enables her to handle these violent genres, but also to give them a very personal touch and deal with them in a very sensitive way,” says film critic and Columbia professor Andrew Sarris ’51CC. “I think The Hurt Locker is one of the best films of the year, and the best I’ve seen about the morass in Iraq.” Sarris also singles out Blue Steel as a favorite. “Her style is — I’ll use the word that Time Out used — seductive."

Bigelow was born in 1951 in the northern California town of San Carlos, where she grew up riding horses and painting. She has a kind of buoyant, outdoorsy vitality, a big-sky embrace of the visual world, and an intense cerebral energy cut with New York punk and what she has called her “semiotic Lacanian deconstructivist saturation.”

A waiter comes by, and Bigelow indicates a nearby heat lamp. “If I could have one of these turned on to, like, nuclear,” she says cheerfully. The waiter obliges.

You think: semiotic Lacanian deconstructivist saturation.

The heat lamp turns bright orange. It starts to get very warm.

That’s when you remove your jacket and ask Ms. Bigelow about her time at Columbia.

"Her attitude: to formalize, to frame, to keep a distance, to control. I think control is essential." — Lotringer

New York City, 1972. Two strangers, a young abstract painter from California and a renowned cultural theorist from France, arrive in Manhattan. One heads uptown, the other, downtown.

The theorist is Sylvère Lotringer. He has just joined the French department at Columbia, where he will introduce, from Europe, the field of semiotics — the science of signs in society. He will also be the first professor in the United States to teach the works of contemporary French thinkers like the philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who claimed — intriguingly, for artists — that the signs and codes found in advertisements create, in the unconscious, desires that cannot be satisfied. For Lacan, desire is predicated on lack.

The abstract painter is Kathryn Bigelow. A student at the San Francisco Art Institute, she’s been awarded a fellowship for the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program. It’s winter and freezing cold. The city is blighted, near bankrupt, dangerous.

“I’ve got a little Levi’s jacket, sneakers, T-shirt. That’s it,” Bigelow recalls. “I decided that wherever my studio was, that was where I was going to live. It was in Tribeca before it was Tribeca — a really rough outpost. I’ve got my sleeping bag and a little dog-eared piece of paper that has my address: ‘Basement of an off-track betting building, three flights down.’ Someone takes me there. There’s no light, footsteps resound off the walls, and the person says, ‘Here’s your studio.’ It’s a bank vault. I think, ‘It’s going to be a little chilly.’ There’s snow outside, and I can’t feel my legs. So I gamely pull out my sleeping bag, praying that somehow the door to the bank vault doesn’t close, because it’s a 24-inch slab of metal. Mind you, there are gunshots echoing every night. And one of my creative advisers is Susan Sontag, which of course meant that I was never happier in my life.”

After completing the Whitney program, Bigelow stayed in New York and began to work with conceptual artists like Lawrence Weiner and the British collaborative Art & Language, which was based on “an attempt to decommodify art, yet still have it be defined as art and justify its existence as art,” Bigelow says. “We were in the Venice Biennale, where we put up a giant banner over the Grand Canal with an inversion of the famous Latin phrase, ‘Art is long, life is short.’ The group is always trying to subvert. Very political in its own way, and insidiously provocative. It made you think.”

With Art & Language, Bigelow started making nonnarrative short films. The group returned to England in 1976, and Bigelow, still in New York, applied for an NEA grant to make a short movie. She got the grant and shot the film, using her conceptual artist friends as crew. But the money ran out before she could edit the piece. “So I think, ‘Aha. Graduate school. Free mix at Trans/Audio!’” She submitted the uncut footage to Milos Forman, who was head of the film department at Columbia. Bigelow was accepted and given a scholarship for an MFA in film criticism.

Sylvère Lotringer, meanwhile, was attempting to bridge the divide between downtown artists and uptown theorists. He taught Lacan and Foucault by day, and, by night, explored the downtown art scene and the prepunk happenings at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. In 1974 he launched a journal called Semiotext(e), a watershed publication that brought art and theory together. The next year, he organized a conference at Columbia on madness and prisons called “Schizo-Culture.” He invited French poststructuralists like Foucault, Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, and Félix Guattari, and artists like Richard Foreman, William Burroughs, and John Cage. The event drew 2000 people.

Afterward, Lotringer was approached by students from the Columbia film department. “Semiotics was in the air,” he says. “Filmmakers were the first to pick up on it. Artists get excited by new ideas earlier than academics. They wanted to know more, so they came to my classes, and that’s how I met them.”

One of those students was Bigelow.

“She came to my class to understand what was going on with semiotics, and Lacan especially,” says Lotringer. “It’s a very controlling thing, to make films. And semiotics is a system of control.”

Bigelow took classes with Lotringer, Marshall Blonsky, Edward Said, and Andrew Sarris, whose two-year film survey was another revelation. “I remember Sarris talking about Orson Welles and The Magnificent Ambersons,” Bigelow says. “To this day I can see him against the screen; he had this almost cherubic smile, infecting everyone in that room with his pure love of film. You walked out of that class unrecognizable, even to yourself. All he did was give his love of film to you and defy you not to pick up on it.”

In 1978, Bigelow completed her thesis, a 20-minute short called The Set-Up. In it, two men have a sloppy fistfight in a dark alley, trading insults of “fascist” and “commie.” As the men tussle, two scholars — Blonsky and Lotringer — deconstruct the action in voice-over.

The following year, Bigelow began working with other students on an issue of Semiotext(e) called “Polysexuality,” which, says Lotringer, “was meant to invent new categories for sexuality, like soft sex or corporate sex, so that nothing could be considered abnormal or deviant. The cover showed a gay biker in San Francisco with a leather jacket and bare ass. On the back was a picture of a man who impaled himself on a giant phallus. Seductive image in front, disquieting image on back. Sex and Death. You give people what they want, but you prevent them from enjoying it in full.”

Fair enough. But what about that Lacanian saturation?

“In Lacan and Deleuze, you have the whole idea of neuroticism and perversion,” Lotringer explains. “For French theorists, perversion is taken more positively than in America. The word has no moral connotation. It means experimenting with your desires, instead of repressing them, as most people do. Neurotics repress things. In perversion, you acknowledge your desires and try them out.”

Cut to Staff Sergeant William James, encased in body armor, in punishing heat, plodding toward a roadside bomb.

Could his courage be a form of Lacanian desire?

“What becomes the discovery in the movie,” Bigelow says, “is that James is actually quite self-aware. He knows what switches him on, and he accepts it. He’s not living in a state of denial.”

The temperature generated by the heat lamp approaches Jordanian highs, and Bigelow graciously asks the waiter to turn it down. She hadn’t actually expected nuclear. “We could warm up half of Southern California,” she jokes.

Just then, a woman comes over. She’s an agent who has been lunching at a nearby table.

“Congratulations,” the agent says to Bigelow. “What an amazing year for you, I mean, all of this attention! Welcome to the Oscars, dear, you’re going to have a lot of opportunities. I think this is your year.” She returns to her table, and comes back a moment later with a well-known actress, whom she introduces to Bigelow. There is no doubt as to which direction the compass needles are pointed.

When the women go, Bigelow returns to Columbia and The Set-Up, to illustrate a central idea about her process.

“I began with The Set-Up to provide a physiological and psychological connection between the audience and the screen,” she says. “While you’re watching it, you’re deconstructing the connection. In a perfect world, theoretically, you’re experiencing that connection.” She then refers to a scene in The Hurt Locker, in which Eldridge, caught in a cross-desert shootout, is ordered by James to grab the ammo from off the body of a fallen comrade. But the bullets, blood-smeared, jam the rifle. With enemy fire whizzing past, Eldridge frantically wipes the bullets, spitting on them to clean them off.

“There was this one article,” Bigelow says, “in which the writer talks about watching the scene and trying to get saliva in his mouth, so that he could help Eldridge clean the bullets.”

It’s what Lacanians call “scopophilia”: the derivation of physical sensation through the act of viewing. Mostly, it is associated with pornography. But it can just as easily be something that makes you wince or cover your eyes.

The explosion rips through the ground, lifting earth in a rolling torrent. Dirt and rust loosen and fly from the shell of a junked car. As Sergeant Thompson is hurled toward us on the road, we see the inside of his helmet turn dark red. He falls, lies motionless. Smoke rises from his body.

The Hurt Locker has just begun. We are about to meet Staff Sergeant James, Thompson’s replacement. With his record of disabling over 800 bombs — 873, to be exact — James, the “wild man,” as a giddy colonel calls him, has come here to do the one thing that makes him feel most alive.

As James is helped into his suit to perform his first death-defying mission with the unit, you seem to hear, in your mind, two disembodied voices, commenting on the text:

“Outwardly,” says Lotringer, “the movie is against violence, but of course, violence is very seductive. And she played with the seduction. To have seduction and Iraq at the same time was a gamble.”

And Bigelow: “The gravity of the subject is encapsulated within this physical beauty that creates a nice tension between the two elements. There’s something interestingly, graphically provocative about a man dressed in a bomb suit lifting up six bombs strapped to a wire.”