The gods came down from Olympus in a line, nearly a thousand strong: Athena with an Afro, Poseidon as a dragonfish, Circe and the Cyclopes. Each was a burst of color in the darkness — vibrant blues, greens, yellows, and reds, painted on crackling paper and mounted on a boxy frame, illuminated from the inside. They were carried by students, professors, parents, and children, making a spectacular parade as they marched from Morningside Park through College Walk on a warm Saturday night last September.

For many participating in the third annual Morningside Lights festival, that evening was a culmination. They’d spent hours over the course of a week spread out on the stage of Miller Theatre, constructing the lanterns in an experiment in collective art-making. Schoolchildren came in class groups; undergraduates stopped by between classes; faculty and community members brought their families. In a creative game of telephone, people started projects and then handed them off to the next group when they left, with notes that said, “Hi. Can you please transform me into a dragonfish?” or “Please finish this in rainbow colors. Extras: Has a monocle; also a moustache.”

But this year, the parade was also a beginning. Called Odysseus on the A Train, it marked the first official campus event in Homer in Harlem, a yearlong series of concerts, films, readings, symposiums, and classes honoring Harlem artist Romare Bearden. As a campus-wide programmatic focus, it is nearly unprecedented. And at its center is one remarkable art exhibit.

Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey brings together the artist’s 1977 series of collages and watercolors based on Homer’s great epic. Six weeks after the parade, the exhibit opened at Columbia’s Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery. Like Odysseus, the works had been on their own long journey, touring the country for the last two years as a part of a Smithsonian Institution traveling exhibition — Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Memphis, Tennessee; Fort Worth, Texas; Madison, Wisconsin; Atlanta, Georgia; Manchester, New Hampshire; and finally the Wallach Gallery in New York, on the edge of Bearden’s beloved Harlem.

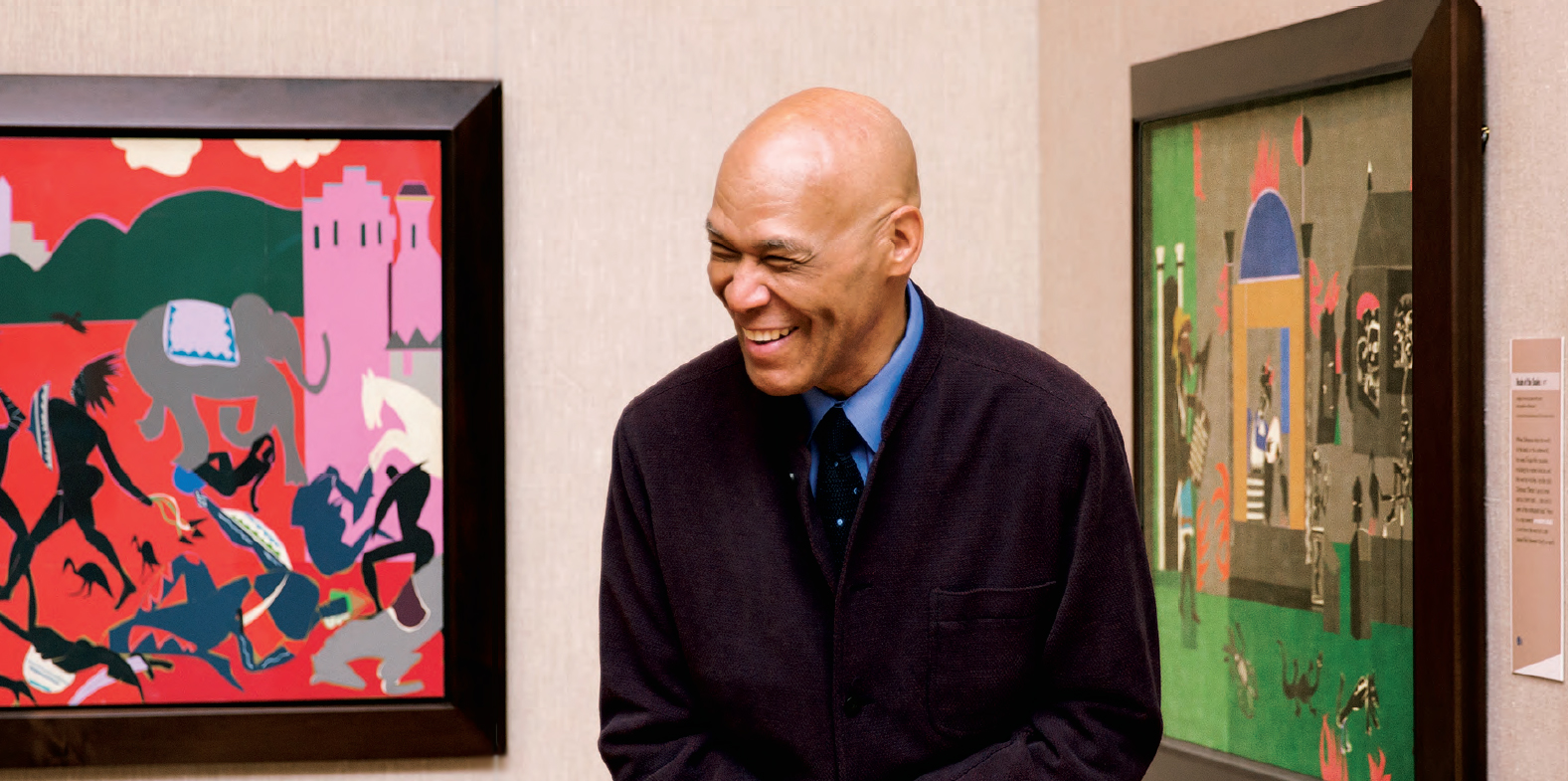

For Robert O’Meally, Columbia’s Zora Neale Hurston Professor of English and Comparative Literature, the founder of its Center for Jazz Studies, and the curator of the Smithsonian’s A Black Odyssey, this was more than just the final stop on a museum tour. As he wound his way through Harlem, up Amsterdam Avenue and onto College Walk, he gazed at the procession and smiled.

“Finally,” he thought, “they’re coming home.”

“Sing to me of the man, muse," begins Homer’s Odyssey in Robert Fagles’s translation, “the man of twists and turns.” This phrase — in the Greek, polytropos — is Homer’s first description of the hero Odysseus. It alludes to his wayward journey home, delayed by battles and vengeful gods. But it also sums up his character: complex and changeable.

“He was a shape shifter,” O’Meally says, “and that’s something that Bearden could relate to. The range of his interests and his influences was just incredible.”

Born in North Carolina and raised in Harlem, Bearden was a cartoonist, a social worker, a writer, an activist, and a prolific painter and collagist. He drew inspiration from Western masters like Matisse and Picasso, but also from African sculpture and masks, and from Byzantine mosaics, Japanese prints, and Chinese calligraphy. His bright collages, watercolors, oils, and photomontages layered together history, literature, music, and many other art forms.

“I once met an art-history professor who said that she could teach an entire survey course just from the influences in Bearden’s paintings,” O’Meally says.

O’Meally was a graduate student at Harvard in the early 1970s, working on a dissertation on Ralph Ellison, when he first met Bearden, and the artist has fascinated him and been a focus of his research ever since. An amateur saxophonist who founded Columbia’s Center for Jazz Studies, O’Meally was drawn to Bearden’s colorful, jazz-inspired collages, some depicting musicians or musical instruments, and others more abstractly embodying the music’s rhythm and spirit of improvisation.

“Bearden said you have to begin somewhere. So you put something down, and then you put something else with it. Once you get going, all sorts of possibilities open up, and things fall into place like fingers on piano keys,” O’Meally says.

In 1977, Bearden made a series of twenty collages based on Homer’s Odyssey. Many of the artist’s fans saw this as a thematic departure: at the time, Bearden’s best-known works were street and music scenes. But it wasn’t his first time illustrating the classics: in the 1940s, when he was only in his thirties, Bearden completed a series of pen-and-ink drawings based on The Iliad, Homer’s epic poem of the Trojan War.

“Bearden was stationed in New York City during World War II, and it was clear that this was on his mind when he was making these drawings. The brutality of war is just so evident,” O’Meally says. “It’s a story that tears you apart, because you’re rooting for the heroes and then you realize that the heroes are bloodthirsty and they’re killing the people and destroying the ones that we also love. It’s a great tragic epic.”

In 2007, the New York gallery DC Moore united for the first time Bearden’s Iliad and Odyssey series, as well as smaller, watercolor versions of the Odyssey collages. O’Meally, who had been teaching Homer for years as a part of Columbia’s Core Lit Hum classes, wrote the catalogue for the show. When a representative from the Smithsonian got the idea to turn it into a traveling exhibit, she turned to him to curate it.

“It was the most seamless thing in the world,” he says. “I was teaching Homer every morning and Bearden every afternoon. It felt like a confluence of everything.”

At Columbia, it was also an exciting time for the Wallach Gallery. After years on the eighth floor of Schermerhorn Hall, the gallery is preparing to move to the Lenfest Center for the Arts on the Manhattanville campus. Guiding that move is director and curator Deborah Cullen, who joined the Wallach Gallery in 2012 after sixteen years as curatorial director of El Museo del Bario in Harlem.

“We’re able to use the gallery as a classroom, both for Columbia students and for K-12 neighborhood school groups,” Cullen says. “As we prepare to expand and be more public-facing on the Manhattanville campus, this is definitely the direction we want our program to go in.”

Once the Wallach Gallery was established as the show’s final domestic stop, O’Meally started thinking about the larger implications for the University. This exhibit, he thought, brought to life a story that every Columbia College student was reading. Students were thinking about Homer in Lit Hum classes, about modernism in Art Hum, and about jazz in Music Hum; the exhibit was the embodiment of the Core Curriculum. He went to President Bollinger with the idea of creating additional programming around the exhibit, and Homer in Harlem was born.

Beginning with the Morningside Lights parade in September, the campus has been packed with events, lectures, screenings, concerts, and readings dedicated to exploring the themes that Bearden brings to life in his work. Rosanna Warren and Alice Oswald have done poetry readings inspired by the work. Families have gathered in the gallery to read Bearden-inspired children’s books. Scholars have convened for panel discussions on gender in Bearden and Homer, and on the meaning of the mythology. At one all-day symposium on improvisation, attendees were encouraged to bring instruments in the hopes of forming an experimental band.

Devyn Tyler ’13CC, an actress who has appeared in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), is working with O’Meally on developing some of the campus programming, which will continue through the spring. In November, she took the lead coordinating a staged reading of The Odyssey, in which she performed with two other actors.

“It’s not a text that you really think of as being performed today,” she says, “but I was surprised at how powerful it was to read it out loud, with images of the Bearden works in the background. I’d read The Odyssey as a student at Columbia, of course, but Bearden really brought it to life for me.”

Tyler, who majored in French, first became acquainted with Bearden while studying abroad in Paris, where she took a class with O’Meally, who was then teaching at Columbia’s Global Center at Reid Hall. “It made such an impact that a group of us still gets together to talk about it two years later,” she says. “It’s exciting to see the rest of the campus joining the conversation.”

Events will continue on campus through the spring, with a film discussion featuring Bearden’s niece, Diedra Harris-Kelley, a string-quartet performance, several seminars and symposiums, a performance by Mike Ladd and Jean Grae, and a student-led staging of The Odyssey.

After the Wallach show closes in March, the original artwork will go back to its owners. Meanwhile, a series of reproductions, along with six Bearden lithographs owned by Columbia, will have begun their own journey, heading abroad for exhibits at Columbia’s Global Centers in Paris and Istanbul, where each will be paired with other region-specific works. The Paris show, which opened on January 19, features reproductions of Henri Matisse’s Odysseus series, originally made to illustrate James Joyce’s Ulysses. The Istanbul exhibit, opening on April 15, will feature works by the Turkish artist Bedri Rahmi Eyuboglu.

“If you look around the exhibit, there are Christian crosses and references to the Hebrew Bible, and even one painting with an Islamic crescent. I think Bearden layers it in that way to make it clear that the home that he’s talking about is a global space. We wanted to celebrate that,” O’Meally says.

It’s likely that the exhibit will continue its tour, perhaps to Columbia’s Studio X in Johannesburg — O’Meally says that possibility is getting more certain every day — and even beyond. He has lofty dreams of taking it to the Columbia Global Center in Beijing, noting that Bearden was a master at lettering and once even studied with a Chinese calligrapher.

For the time being, though, Bearden has reached his Ithaca. And so has O’Meally.

“I had tears in my eyes the first time I saw the exhibit hanging here,” he says. “And when I saw schoolchildren with those beautiful lanterns. Bearden has said that all of us are on an odyssey. For me, that means making sure that our students and that people in our community think that Romare Bearden is someone to know about. If that happens, I’ll be the happiest man in New York.”

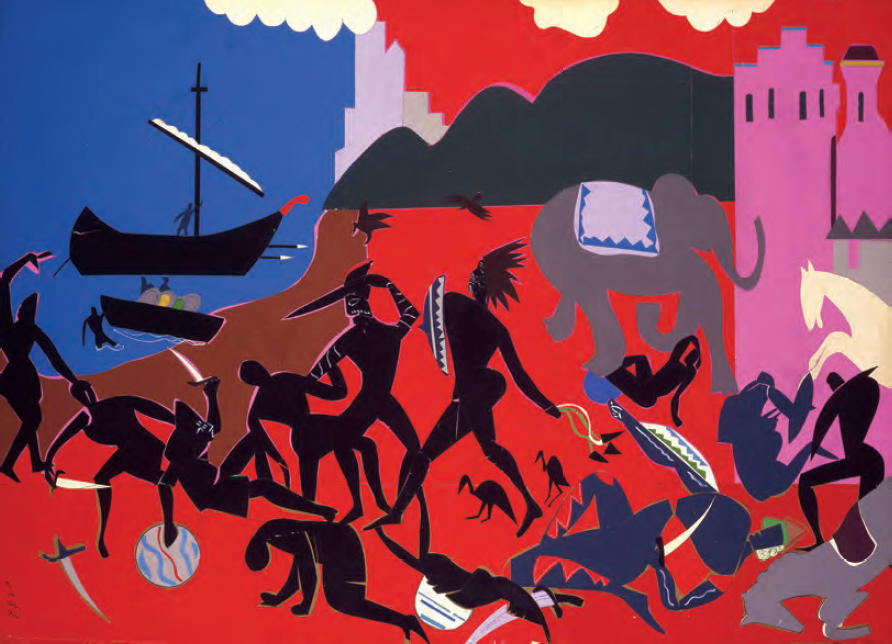

Battle with Cicones

On their way home from Troy, Odysseus and his men take a detour to attack Ismarus, the city of the tribe of the Cicones. They’re enjoying their spoils when Ciconian reinforcements arrive and drive Odysseus and his men back to their ships.

“One of them seems to be in a Native American headdress. What does that mean?” asks O’Meally. “Bearden is making us wonder about questions of race and of nation, of colonial exploitation and of leadership. Homer lets us know here that Odysseus is flawed, just like the rest of us. He’s heroic in so many ways. He’s a terrific athlete, he’s a wonderful storyteller. He’s a military strategist. He’s a fanciful lover, with goddesses fighting over him. And yet he’s impulsive and foolish.”

Poseidon, the Sea God

Poseidon is Odysseus’s great enemy. After Odysseus gouges out the eye of Poseidon’s son, Poseidon is enraged and vows to keep Odysseus away from the seas for ten years.

“Bearden is as concerned about family as he is about heroism and war,” says O’Meally. “Why is Poseidon angry? Because Odysseus put his son’s eye out. Let’s put it in context. This is 1977. African-American children have been mistreated. Bearden seized on the idea that there’s a black father that’s mad about the mistreatment of his family. I think that’s what gives part of the force and the fierceness to this particular image.”

Circe

Circe is an enchantress who transforms Odysseus’s men into swine. Odysseus makes a deal with her: turn his men back into men, and he will stay with her for a year as her lover. She agrees, and after a year of feasting, Odysseus and his crew leave her.

“There are more images of Circe in the series than of any other figure from the epic, including Odysseus,” says O’Meally. “Here she’s depicted like an African queen, which could evoke the ‘conjure woman,’ a priestess who carried on West African traditions. I think Bearden loves her for her special allure, and also because she is so unpredictable in her powers.”

The Siren's Song

Circe tells Odysseus that as he sails away from her island, he must bypass the beautiful but deadly Sirens, because any man that hears their song will die from its sweetness.

“Odysseus is so curious and so much in love with the world as we have it, the good and the bad, the enticing and the forbidding, that he wants to hear that song,” says O’Meally. “And so he has his men tie him to the mast of the ship. He makes them plug their own ears so they will not hear the song and be killed by it. Our love for him is increased, because he is so human, after all. He’s not so big and magnificent. He’s like us. This might be my favorite piece in the series. There’s just so much joy here.”

The Sea Nymph

Poseidon summons a storm that knocks Odysseus into the sea. Ino, a sea goddess, rescues him with a magical veil.

“Here’s the black woman again,” says O’Meally. “She’s the one that goes down when the black man is seeing nothing but deadly trouble and manages to gently bring him to the surface. There’s a kind of angel of salvation that’s presented by this voluptuous figure.

“The influences from Matisse’s cutouts are evident. It’s as if Bearden is saying, ‘I saw your series, and I’m not going to do anything like it. But I will honor it in this little way.’ I love the confidence with which Bearden uses his influences. He knows it looks like Matisse. But it’s not. It’s wholly Bearden.”

Home to Ithaca

In Homer’s story, Odysseus is fast asleep when his ship arrives home in Ithaca. But Bearden reimagines the scene as a moment of triumph, with Odysseus standing heroically at the ship’s bow.

Bearden believed that “The Odyssey” was an epic that embodied the African-American experience.

“I think it was important to him as a black painter to say that this story belongs as much to us as to everyone else,” says O’Meally. “Part of the reason that he chose 'The Odyssey' was that the story of the African-Americans’ journey from Africa through slavery toward freedom is as great an epic story as there is.”