“I know who I am, I know what I do, and I’m not interested in showing off. You get past that quick,” says Doug Morris ’60CC, seated ankle-over-knee on the taupe-and-cream sofa in his office on lower Madison Avenue. “I’m interested in doing a good job, and that’s about it. That’s really the truth.”

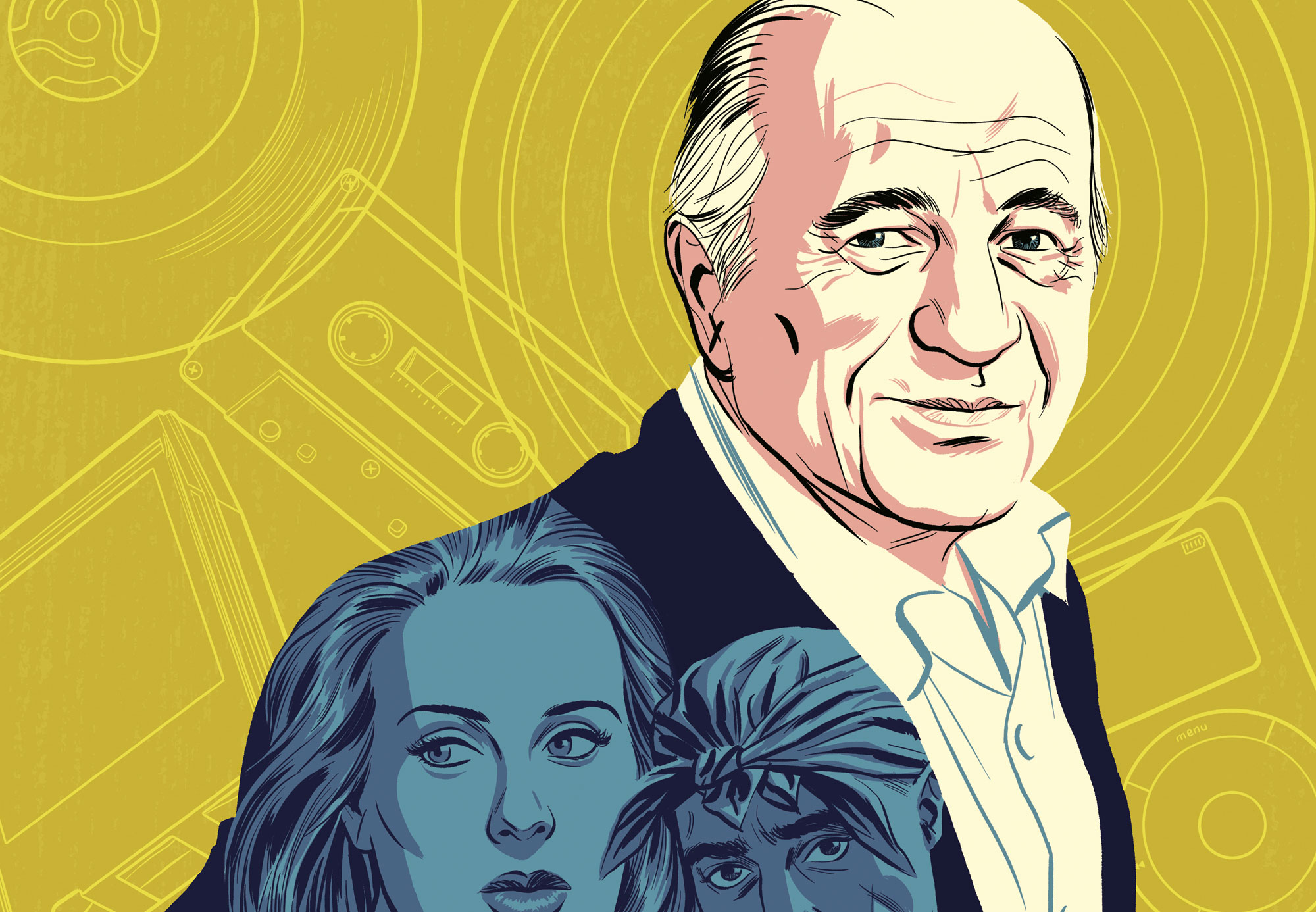

Morris, seventy-nine, compact, barrel-chested, dressed in an impeccably tailored dark suit and striped tie, his brow grooved like a musical staff, his head hedged with combed-back white, is the jukebox hero you never heard of. As the only person to run each of the “Big Three” record companies — Warner, Universal, and Sony — Morris has presided over rosters of artists whose gazillion-selling records are the soundtrack of modern life: U2, Stevie Nicks, Led Zeppelin, Phil Collins, Foreigner, Dr. Dre, Tupac Shakur, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, Mariah Carey, Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Adele, Lady Gaga, Kanye West, Taylor Swift, and many more, including his favorite act, the Rolling Stones, which Morris pronounces with an emphasis on the first word. His delivery of retro syllabic stresses (Broadway is Broadway) and dropped Rs is classic “New Yawk”; U2’s Bono is said to do a spot-on imitation.

Morris got his start in the “rekkid business” in the early 1960s, in the tiny, cigar-stained offices of those Brill Building–era music factories near Times Square. His current office is more ample. In 2011, at age seventy-three, Morris became chairman and CEO of the Sony Music Group and led Sony to six straight years of increased profit and market share before handing off day-to-day operations last year. He was named chairman in 2017 — a mostly ceremonial position, as Morris would be the first to tell you.

Ensconced in a sunny chamber with high ceilings, a baby grand piano, and an uptown view of the Chrysler Building, Morris is surrounded by mementos: a painting by Bono that Morris bought to benefit the Irish Hospice Foundation (“not only is Bono brilliant, he is so generous and nice it defies anything”); a signed Robert Rauschenberg Earth Day poster from Morris’s late friend and colleague Ahmet Ertegun, founder of Atlantic Records (“the most remarkable, brilliant person you could ever meet”); and, on the table, a circa 1995 photo of Morris with Tupac, Snoop, and Suge Knight.

Morris, a family man with a wife, two sons, and six grandchildren, has never been fodder for the tabloids. Elegant and understated, he rejects the cultural stereotype of the debauched record mogul hoovering cocaine off his desk. “There are a lot of lovely, lovely people in the business,” he says. “It’s a business for people who love music. That’s what it is.”

Morris began his career as a musician. At age ten, he was writing songs at the family piano, back when the year’s chart-topper was Dinah Shore’s “Buttons and Bows.” Then, in 1955, at seventeen — A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom! The seminal cry of rock ’n’ roll buzzed Morris’s ears. “Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino — it was a revolution in music, and I loved it,” he says.

Morris’s parents were concerned. His father, Walter Bernard Morris ’21CC, ’23LAW was a lawyer; his mother, a ballet instructor. They lived in Woodmere, Long Island, one of the Five Towns, where generally the notion was that your son would go to college and enter an established, stable profession, not one that involved plunking out three-chord ditties about girls. “The big question in my family,” says Morris, “was, ‘Who’s gonna take care of Doug?’”

At Columbia, Morris, handsome and charismatic, majored in sociology and economics. By his own account “a terrible student,” he was a member of the glee club (“it was an honor to be included”) and even crooned once or twice at the Friday Night Dance in John Jay Hall. “I had one goal in college,” says Morris, “and that was to get ahead in the music business.”

Between classes, he’d take the subway to the record-factory mecca of Midtown and show his songs to Lou Levy, a Tin Pan Alley–era music publisher whose catalog included “Strangers in the Night” and “The Girl from Ipanema.” Levy offered Morris twenty-five dollars a week to write for his company, Leeds Music. Levy then shared one of Morris’s compositions with Jim Fogelson, “a famous A&R man who signed me, believe it or not, to Epic Records,” now a division of Sony. The song, a piano-banger with Elvis-like vocal reverb called “Frigid Digit,” got a brief notice in the October 29, 1960, issue of the music-industry magazine Cash Box, which called it “a rocker of questionable taste.” Morris reports that a friend just sent him a copy. “He got it for five dollars on eBay.”

Morris smiles. He can poke fun at himself, but at his core, never far from the surface, lies the mettle and command of the nine-figure dealmaker. A soft-spoken leader (“I hate screamers”), he’s also a sensitive listener: Ertegun called him “the finest record man I ever worked with,” and Grammy-winning singer Mary J. Blige, at the unveiling of Morris’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2010, called him “my father in the music business.”

But what really distinguishes Morris from many record executives is his firsthand knowledge of the creative side. “I know what it feels like when a record does well, and I know what it feels like when it bombs,” he says. “I know the anticipation and excitement, and I know the disappointment. I think understanding how artists feel when they put out a record has helped me in my career.”

Morris’s first big smash came in 1966, while working as a songwriter and producer for Laurie Records, whose top act was the Chiffons, known for hits like “He’s So Fine” and “One Fine Day.” Morris spent a week writing a new song for the group called “Sweet Talkin’ Guy.” The record, which Morris also produced, reached number ten on the Billboard charts.

Shortly afterward, Morris was promoted to executive vice president of Laurie. An A&R man now, his job was no longer to write songs; it was to find them.

Identifying a hit song requires intuition and intellect, which for Morris translates to a simple, binary question. “Either you like it or you don’t,” he says, with a wave of his hand.

Morris isn’t being glib. He speaks in essences, like some inverted Dylan, all enlightened literalness instead of riddles. For Morris, the secret of the record business isn’t very complicated at all.

“It starts with the song,” he says. “If you don’t have a song, you have nothing.”

This lesson was brought home in the spring of 1967, when Morris was at Laurie Records. A band from Ohio, the Music Explosion, sent Morris a song called “Little Bit O’ Soul.” Morris liked it and bought the master for five hundred bucks. Laurie released the record, catalog number 3380. This would be Morris’s case study for deciphering the music business.

Morris hadn’t thought much about what actually happens to a record once it goes out into the universe. Then one day, seated at his desk behind the sales executive, Murray Singer, Morris saw, on Singer’s desk, an order for three hundred copies of Laurie 3380. His first order! And a big one, too. Excited, Morris asked Singer who placed it, but Singer, busy, dismissed it as a blip, not worth pursuing. So Morris investigated. He traced the order to two stores in the town of Cumberland, Maryland. Morris had never heard of the place. He called the stores and asked the clerks what was going on. They told him that a local disc jockey played the record and started getting requests from all over the state. Now the discs were flying off the shelves.

Morris told his bosses at Laurie, and they began promoting the record. The song charted in June, and by July 1967, “Little Bit O’Soul” was number two in America.

That’s when Morris realized: you don’t manufacture a hit, simply by playing it over and over. People have to ask for it. They have to want it. And if a record sparks, you fan that little flame with all you’ve got.

The insight emboldened Morris to start his own label, Big Tree Records, in 1970. “We didn’t have very much money, and I didn’t know anyone,” he says. “I just thought I would know how to make good records. And we got hits right away.” In 1971, Lobo’s “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo,” a strummy ode to itinerant road life, peaked at number five. Two years later, Morris cowrote and produced a song buried on the B-side of an album by the hard-rock trio Brownsville Station. Few listeners would have guessed that the song, “Smokin’ in the Boys’ Room,” with its musk of lavatory stalls and juvenile rebellion, was the brainchild of a thirty-five-year-old Ivy League graduate. Still, Morris thought it was too close to “Jailhouse Rock” and didn’t release it as a single. Yet magic happened: “A DJ in Portland, Maine, started playing it, and in two days it was the most requested song in the city,” Morris says. So, following the formula for “Little Bit O’ Soul,” Big Tree got behind the song, and it climbed to number three in the country, an anthem for long-haired teenage boys.

Morris says that this sort of radio-based grassroots miracle — the local DJ who starts a wildfire with a single spark — still happens, as in the case of 2015’s “Fight Song” by Rachel Platten, which went to number one on the adult charts. “A small station in Baltimore played it, and two days later people had bought five hundred copies,” Morris says. “We picked up the record and sold several million.”

At Big Tree, Morris put out other million-sellers: the dance-floor pop-funk of “You Sexy Thing” by Hot Chocolate (number three) and the mellow mustache-and-heartstring longings of “I’d Really Love to See You Tonight” (number two) by England Dan and John Ford Coley.

Big Tree was bearing fruit, and in 1978, Morris got a phone call from Jerry Greenberg at Atlantic Records. Greenberg said that his boss, Ahmet, would like to talk.

Ahmet Ertegun: the bald, bespectacled, worldly, earthy, neatly goateed son of the Turkish ambassador to the US, devotee of Black American music, signer of Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin, illustrious bon vivant, and the subject, in 1978, of a thirty-five-thousand-word profile in the New Yorker. “I was beyond excited,” Morris says. “I went to Ahmet’s office at Atlantic, and he said he liked what we were doing and that he wanted to buy Big Tree and have me run the Atlantic sub-label Atco, which had, believe it or not, Swan Song Records — Led Zeppelin’s custom label — and Rolling Stones Records.”

Morris was going electric. From England Dan to England Mick. It was radical. He had always been a songs guy, a singles guy, but this scene was the album, that ambitious, unified musical statement, requiring long-term commitment and cultivation. “I grew a beard and got a gold watch,” Morris says with a chuckle. “I signed Stevie [Nicks] from Fleetwood Mac and Pete Townsend from the Who.” Morris and Ertegun worked in adjoining offices, and “we began each day with a high-five and ended it with a hug.” In 1980, Ertegun made Morris president of Atlantic. One of Morris’s first tasks was to find a producer for Nicks.

He called Jimmy Iovine, a skinny twenty-six-year-old kid from Red Hook who produced Patti Smith’s single “Because the Night” and Tom Petty’s album Damn the Torpedoes. “He was just so smart and talented,” Morris says. “You couldn’t stop Jimmy with a machine gun.” Iovine agreed to produce Nicks’s album Bella Donna, which hit number one in America.

Morris’s stock continued to rise, and in 1990 he was named co-chairman and co-CEO, with Ertegun, of Warner Music Group, Atlantic’s parent company. That year, Morris, in a move that would have enormous global impact, put up half the money for Iovine’s new label, Interscope.

Morris was taken with Iovine’s “ability to see around corners,” and when Iovine told him that hardcore West Coast rap, still a niche genre, was going to go mainstream, Morris listened. In 1992, the pair flew to post-riot Los Angeles to meet with Marion “Suge” Knight, the imposing three-hundred-pound cofounder, with Dr. Dre, of Death Row Records, and a reputed member of the LA gang the Bloods. Knight agreed to a distribution deal with Interscope. Death Row, home to Dre, Snoop, and Tupac, entered the Warner fold.

The West Coast style, known as “gangsta rap,” indeed blew up, and Warner was red-hot. Morris was named chairman and CEO of Warner Music US. But trouble was around the corner. Rap had come under scrutiny. People like former US drug czar William Bennett and US senator Robert Dole sounded the alarm about the effects of albums like Doggystyle on America’s youth. Along with activist C. Delores Tucker, chairwoman of the National Political Congress of Black Women, they prevailed upon the Time Warner board to stop distributing rap music with violent or misogynistic lyrics.

Morris, congenitally averse to censorship, stood by the rappers, whom he saw as vital artists channeling their own experience. Rifts opened in the company over what to do. In June of 1995, Morris’s boss, Michael Fuchs, the former chief of HBO and head of Warner’s worldwide music division, summoned Morris to his office. Warner was having its best year ever, so Morris expected a positive encounter. It was an incredible shock, then, when Fuchs fired him. “Thrown out the window and splat on the pavement” is how Morris puts it. “The whole thing was very painful. But what I learned is that it’s not how you go down, it’s how you get up.”

Hours after his firing, Morris got a call from Seagram’s CEO, Edgar Bronfman Jr., who owned MCA Music Entertainment, an ossified outfit known in the industry as Music Cemetery of America. Bronfman wanted Morris to raise the dead. Morris accepted. When Fuchs, to complete the rap purge, cut ties with Interscope, Morris pounced: he called Iovine and convinced him to sell 50 percent of Interscope to MCA for $200 million. Morris and Bronfman renamed the company Universal Music Group, and Morris assembled a hit squad: U2, Mariah Carey, Snoop, Tupac, Eminem. CD sales soared, and by the turn of the millennium, Universal’s market share peaked at nearly 40 percent, with profits of more than one billion dollars — the biggest record company in the world.

It’s not for nothing that Bono once called Morris “a character who has risen several times from the ashes.”

In his excellent 2015 book How Music Got Free: A Story of Obsession and Invention, Stephen Witt ’11JRN tells how the record industry, personified by Morris at Universal, was nearly consumed by the flames of digital technology.

In 1996, a highly compressed audio-coding format called MP3 was patented in the US. This innovation allowed people to store songs on their computers and transmit them online. Soon, digital-audio exchanges like Napster (launched in 1999) appeared, attracting millions of erstwhile CD purchasers who could now download music for free.

“File sharing,” they called it. Morris preferred “stealing.”

In Witt’s account, record executives, attached to the lush margins and unmatched profits of the fourteen-dollar compact disc, were slow to respond to the digital revolution.

Piracy spread, CD sales plunged, and the industry was upended. Thousands of jobs were lost.

At first, Morris wasn’t sure what to do. He wasn’t a tech guy. He knew rhythm and blues, not algorithms and bytes. He also knew ledger balances and copyright law. And he took it personally when artists got cheated. It was Morris who, through the Recording Industry Association of America, brought the legal fight to Napster (shuttered in 2001) and LimeWire (found liable for copyright infringement in 2010). And it was Morris who got pilloried in the tech press for suggesting that the record industry, made up of music lovers and not technologists, was naturally unprepared to adapt quickly and efficiently to the Internet. Tech pundits derided him as a relic, out of touch, the face of an outmoded industry.

“What people don’t realize,” says Morris, “is that there were huge companies that tried and failed to monetize digital music. Microsoft, Sony. People said, ‘Why didn’t you guys do it?’ Because we’re musicians, we don’t know how. ‘Why didn’t you hire someone?’ Well, if Microsoft and Sony couldn’t do it, we weren’t going to do it.”

The guy who did it was Apple cofounder and CEO Steve Jobs. In 2001, Jobs came to Morris’s office and “articulated a clear thought that went from buying songs on iTunes to downloading them onto the iPod — it made a lot of sense,” Morris says. Though his bosses fretted because the new scheme would “unbundle” the album — letting consumers buy individual songs for ninety-nine cents apiece — Morris reasoned that most of Universal’s music was being stolen anyhow. And so he licensed all of it to Apple.

Today, in the post-CD era, the American record industry generates about half of the fifteen billion dollars it earned in 1999. But revenues are rising. “We’re coming back slowly,” says Morris, pointing to popular streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music and to the online music-video platform Vevo, which Morris cofounded in 2009 with the idea that if you sifted out the premium music videos from the junk-filled seas of the Internet and gathered them in one place, you could sell ads, licensing rights, and subscriptions.

Vevo now gets twenty-five billion views per month, and grossed $650 million in 2017, breaking even for the first time, with profits expected in 2018.

“I don’t know anything about technology,” says Morris, his arm stretched out on the sofa back. “I know common sense.”

The phone rings. Morris picks up.

“Good morning, Jimmy,” he says, breaking into a warm, bright smile. Morris and Iovine still speak every day, a habit of thirty-five years. “I just read the article. I thought it was terrific.”

Morris is referring to a Billboard piece in which Iovine, now the head of Apple Music, disputes what he sees as a too-optimistic Wall Street report on the economics of music streaming. “It’s interesting,” Morris tells him, “because you’re going against all the conventional wisdom. It’s gonna cause some controversy, Jimmy.”

As Morris talks, it’s plain that his magnetism is bound up in his lively interest in others, in the refined pleasure he takes in their gifts. “Really smart, Jimmy,” he says. “Really, really smart. All right, kiddo. See ya later, pal.”

Iovine calls Morris “one of the greatest executives for executives ever,” and Morris is as esteemed in the industry for his recruitment and nurturing of executive talent as he is for his hit-making. In 1990 he hired Sylvia Rhone to run Atlantic’s East West Records — the first Black woman to head a major label and soon the most powerful woman in the business (she now runs Epic Records). There’s Craig Kallman, CEO of Atlantic Records (“I knew who he was and what he would become”), Monte Lipman, CEO of Republic Records (“I met him and knew he was something special”), and many more. “It’s all about recognizing the brilliance in other people,” Morris says.

This spirit extends to his management philosophy, which he sums up in two words: be nice. “Everyone has feelings and the need to feel included, and that’s what I always did. I never wanted anyone to leave the office and have a bad night. Everyone likes to be respected, paid well, appreciated for what they contribute. And when you do that day in and day out, people start believing in you.” Morris gives a verbal shrug. “I like to be treated nice, and I figure everyone else does. It’s not rocket science.”

Not for Morris, it isn’t. You like it or you don’t. It’s not how you go down, it’s how you get up. And if you don’t have a song, you have nothing.

Morris has songs. Again.

Shortly after speaking with Columbia Magazine, Morris, never down for the count, announces a new venture. He has secured the funding for an independent record company called 12 Tone. Nearly fifty years after founding Big Tree, Morris is getting back to his roots: heading up his own label.

This time, however, there won’t be vinyl or CDs. With streaming, you don’t need any sort of disc. Technology has changed, but music is still music. And Morris is still a passionate suitor.

“The one thing I learned is, no matter how you push to do other things, fight to make a living doing what you love,” he says.

Of all Morris’s maxims, this one carries the full weight of a sixty-year career.

“I’m telling you,” he says, like a songwriter reworking a line, finding the kernel, the universal vein. “If there’s something you love, you fight for it.”