Tsechu Dolma

Helping mountain communities adapt to climate change

High in the Himalayas along the border between Nepal and China, thousands of Tibetan refugees, most of them stateless and without legal documentation, live in struggling farming communities. Isolated physically, economically, and politically, many families go hungry. Literacy rates are low, and human trafficking is on the rise. And now those farmers have another significant challenge to add to their list: climate change.

“Temperatures in the Himalayas are warming at approximately twice the global rate,” says Tsechu Dolma ’14BC, ’15SIPA, who is helping Tibetans in Nepal improve their livelihoods through her nonprofit, the Mountain Resiliency Project (MRP). “Glaciers are melting, and weather patterns are erratic. Farmers face flash floods, shortened growing seasons, and unreliable access to water.”

MRP, an economic- and community-development organization, works with refugee farmers in the Himalayas to grow, harvest, and sell crops, such as mushrooms, that thrive in greenhouses regardless of changing weather conditions, and to produce honey from native bees. “We’re strengthening the food security in the region so that agriculture will continue to be a huge percentage of the local GDP,” says Dolma. MRP also runs educational workshops for local women on topics including sexual health and financial empowerment.

For Dolma, the problems in the mountains are deeply personal. She spent the first ten years of her life in a refugee settlement in Nepal before her family found political asylum in the United States. They ended up in Queens and lived in public housing. “Growing up, I didn’t think about college,” says Dolma, whose parents have no formal education. “But eventually I learned about a school called Columbia that was just a subway ride away.” She got a full scholarship to Barnard and, while still an undergraduate student, began a master’s program at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs. A grant from the University enabled Dolma to launch MRP in 2012 as part of her thesis project. “I never thought it would lead to a thriving startup with a full-time staff of fifteen,” she says.

Since then, MRP has partnered with aid organizations such the US State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration to help fifteen thousand Tibetan farmers, many of them women, become economically self-sufficient. The nonprofit has also improved infrastructure in the mountains: after a devastating earthquake hit Nepal in 2015, MRP helped construct two hundred new homes.

Dolma is now taking a one-year hiatus from running the organization to pursue an MBA at the University of Oxford as a Skoll Scholar (a program for social entrepreneurs). After years of doing fieldwork, she says she wants to become a better international businesswoman and broaden her humanitarian outreach beyond the Himalayas. “To really make systemic change we have to think big, and thinking big means stepping out of Nepal,” says Dolma. “My dream, my family’s dream, my community’s dream, is to build a global network of climate-vulnerable refugees who can support each other by starting their own sustainable business ventures.”

Atti Worku

Educating the next generation of Ethiopians

Growing up in Adama, Ethiopia, Atti Worku ’14GS understood that she was different from other kids. Her mother and father were educated and middle-class; other families could barely afford food. Worku had access to books and was sent to private school, not the overcrowded public schools that were short on teachers and resources. And while Worku finished high school, most of the poorer kids in Adama dropped out — to work or simply because they couldn’t afford uniforms and school supplies. “I always wanted to do something about the problems I saw, but I didn’t know how,” Worku says.

Two decades later, Worku is developing her own solution to the social inequalities she witnessed as a kid. As the founder and CEO of Seeds of Africa, an education and economic-development nonprofit, she operates a free, high-quality K–12 school in Adama for children whose parents earn less than the equivalent of around $1.50 a day. The school provides nutritious meals, health-care services, uniforms, and school supplies for all students. “When children have challenges at home, education on its own is not going to make a difference,” says Worku. “So we provide the things that allow them to stay in school, graduate, and have a better life.”

Worku had an unconventional route to entrepreneurship. She studied computer science in Addis Ababa and briefly worked as a network engineer before leaving college to pursue modeling. She moved to South Africa, competed in beauty pageants throughout the continent, and in 2005 represented Ethiopia at the Miss Universe competition in Bangkok, where she advocated for expanding access to technology in her home country.

After Miss Universe, Worku moved to the United States and settled in New York City. Though she continued to model, her sights were set on humanitarian work. “I realized I had to use my influence for something impactful,” she says. She came up with the idea for Seeds of Africa and collaborated with her family and professional contacts to open the school. “The beauty of working in fashion is I met a lot of philanthropic people, and they believed in me,” says Worku. A few years after starting the organization, Worku got a degree in sustainability management from Columbia’s School of General Studies. “My classes helped me make connections between Ethiopia’s problems and global issues surrounding poverty, climate change, and women’s and children’s rights,” she says.

Along with improving education, Worku wants to advocate for socioeconomic reform in Ethiopia. Seeds of Africa recently launched a microfinancing program that has helped more than two hundred local Adama women — many of them single mothers — open bread shops, farm stands, hair-braiding salons, and other businesses. “We see at least a 50 percent increase in household income,” Worku says. “That means a family could potentially have three meals a day instead of two.” Loan sizes average around three hundred US dollars, and more than 96 percent are paid back within a year.

Worku stresses the importance of truly understanding a community’s needs before trying to intervene. “Part of the reason so many aid endeavors have failed in Africa is that a lot of well-intentioned people haven’t addressed the deep-rooted problems, just the symptoms,” she says. “We take a holistic approach, working with entire communities to ensure that more children and women benefit from the type of support system that I’ve been lucky to have.”

Aline Sara

Connecting foreign-language students with refugee tutors

Aline Sara ’14SIPA, a former journalist who spent several years in Beirut covering the Arab Spring, was applying for humanitarian jobs in the Middle East and trying to brush up on her Arabic when she had the “aha” moment that would lead to an ambitious business venture. “What if there were a startup that helped you learn Arabic, and your tutor was a Syrian refugee who really needed income?” she asked herself.

The year was 2014, and more than a million Syrian refugees had migrated to Lebanon to flee the civil war and ISIS. Denied work visas by the Lebanese government, most had no way of earning a living. “When refugees cross borders, the vast majority, especially the educated middle class — the doctors, lawyers, journalists, teachers — have a very slim chance of finding work,” Sara explains. “Just imagine: you’ve watched your country crumble, you’ve likely lived through trauma — loss, incarceration, near-death experiences — and then you escape to a place where you can’t restart your life.”

Sara, who was born in New York City to Lebanese immigrants and grew up speaking English and French, decided to do something to help. She teamed up with her Columbia peer Reza Rahnema ’14SIPA and launched NaTakallam (Arabic for “we speak”), an online language-learning and cultural-exchange program that hires refugees as freelance contractors. Sara runs the for-profit company from the Columbia Startup Lab in New York City, while Rahnema, the COO, heads operations from a Paris office.

NaTakallam connects language students with refugees from the Middle East, Latin America, and Francophone Africa for conversation practice over Skype. For fifteen dollars an hour, anyone can sign up for a session in Arabic, Persian, Spanish, or French, though the company gets most of its business through organizations. More than twenty universities — including Columbia and Yale — have partnered with NaTakallam to incorporate conversation practice into their foreign-language programs, and NaTakallam has helped more than two hundred K–12 schools to bring refugees into their classrooms (also through Skype) as virtual guest speakers. A social-studies class, for example, can invite a migrant from Venezuela to talk to students about the human impact of the country’s economic collapse.

NaTakallam, which also offers translation and transcription services, strives to pay contractors at least the minimum wage in their host countries. Sara says that the company has distributed some $600,000 to 150 displaced individuals. But the impact goes beyond financial. In facilitating face-to-face interaction, NaTakallam promotes empathy for refugees and combats negative stereotypes. “We try to bring awareness to the fact that there are all kinds of people in refugee populations, because the media tends to give a very negative image,” says Sara, who adds that some of NaTakallam’s tutors have found more work and even opportunities for resettlement through their students.

“Being a refugee is isolating,” Sara says. “A lot of social enterprises will hire displaced people to do artisan work or data entry behind a computer. Those jobs are important because they generate income, but they’re still isolating. Human connection and warmth have ripple effects, and what we’re doing is creating new, empathy-filled virtual networks.”

Sylvana Q. Sinha

Improving health care in Bangladesh

Sylvana Q. Sinha ’04LAW, an international lawyer and foreign-policy expert, never planned on becoming a health-care executive. But in 2010, after her mother suffered from serious complications after an appendectomy at one of Bangladesh’s top hospitals, Sinha set her ambitions on improving the medical-care options in her parents’ home country.

“Every day, thousands of middle-class Bangladeshis — people who can barely afford to travel — go to India for medical treatment,” says Sinha, who grew up in Virginia but developed a strong personal connection to Bangladesh and its culture. “People have lost trust in the health-care system. I have some family members who have been falsely diagnosed with cancer, or they had cancer but it wasn’t diagnosed.”

Sinha founded Praava Health in 2014 to help the country’s growing middle class access high-quality, affordable treatment close to home. Its ten-story outpatient clinic in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital and largest city, offers a wide range of family-health and diagnostic services, and since opening in 2017 has served twenty-five thousand people. The average doctor visit in Bangladesh lasts forty-eight seconds, but Praava’s patients are guaranteed fifteen minutes, says Sinha, who relocated from New York City to Dhaka in 2015. “If you invest in doctor-patient relationships, you get better health outcomes.”

The for-profit company, which charges significantly less than other private facilities, has the nation’s first molecular-diagnostics lab to detect cancer, and its most sophisticated hospital information system. “This is a country where people carry around their medical records in bags,” says Sinha. “We store everything electronically in one place. Patients can access their records and book appointments online.” Counterfeit drugs are ubiquitous in Bangladesh, so Praava also has an in-house pharmacy that sources all medications directly from manufacturers.

Before she became an entrepreneur, Sinha, who studied law at Columbia and international development at Harvard, worked as a policy adviser to then senator Barack Obama ’83CC. In 2008 she moved to Afghanistan, where she worked on development and legal-reform projects. Though Sinha originally planned a government career in foreign policy after returning to the United States, she saw more opportunity for social impact in the private sector. “I wanted to make people’s lives better, and I felt like participating in politics wouldn’t allow me to do that in the way I craved,” she says.

The health-care industry presented an attractive challenge. “I think what’s exciting about health care is that nobody has really figured it out,” says Sinha. Her goals for Praava are ambitious, but with ten new facilities scheduled to open in the next three years, she’s making progress. “We’re building the best health-care company in Bangladesh,” she says. “There are 170 million people in the country, so we have big dreams, and we hope to serve a broader segment of the population over time. We’re planning to launch a nonprofit that will reduce financial barriers for patients, improve skills for care providers, and support research. We’re just getting started!”

Sabrina Natasha Habib

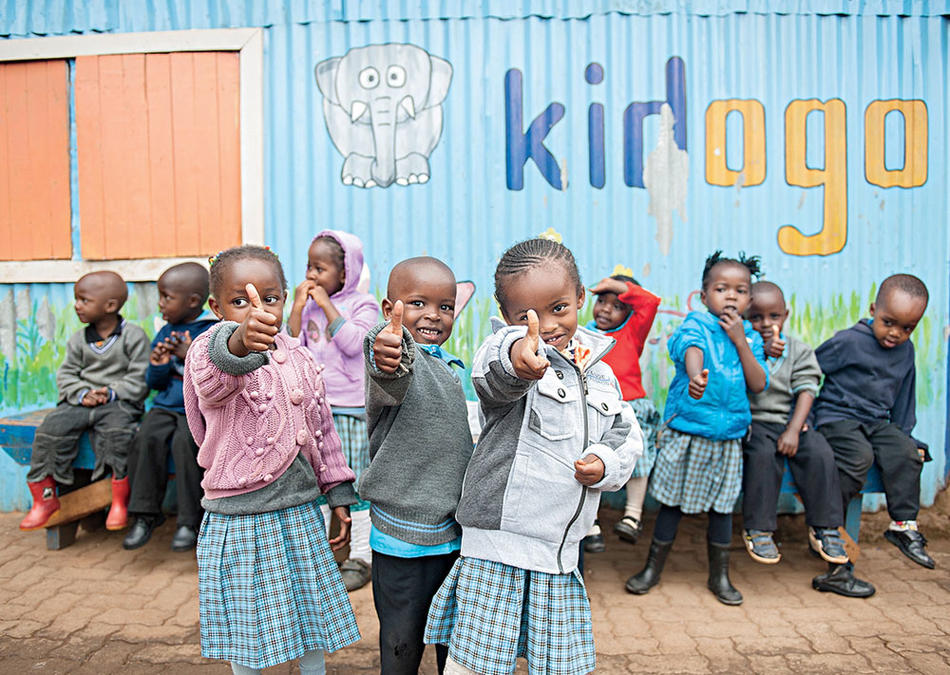

Expanding access to quality childcare in Kenya

In 2011, Sabrina Natasha Habib ’16SIPA was in Kenya completing a fellowship in maternal and child health when she stumbled — literally — upon what she calls East Africa’s “childcare crisis.” As Habib recalls, she walked into a day-care center in a Nairobi slum and almost tripped over an infant. “The room was dark and crowded, and I couldn’t even see where I was walking,” says Habib, now the cofounder and CEO of Kidogo, a network of high-quality day-care centers in Nairobi. Struck by the unsafe, unsanitary conditions, Habib began to look deeper into the problem of childcare in East Africa’s low-income urban communities.

“In Nairobi alone, there are approximately three thousand informal day cares, many in corrugated-metal shacks,” says Habib, who was born and raised in Toronto but whose parents are from Tanzania. “There’s little stimulation. They’re just awful for a child’s development.”

Mothers here, most of whom earn money through informal jobs — washing clothes or selling produce on the street, for example — are forced to return to work directly after giving birth, explains Habib: “There’s no such thing as maternity leave for these women. Parents have few choices. They leave their babies home alone, sometimes tied to furniture, or with an older sibling — usually a girl — who has been pulled out of school, or, if they can scrape together the cost, in some type of day care.”

Habib, who lives in Nairobi with her husband and Kidogo cofounder, Afzal, started the nonprofit in 2014 to provide families with safe, stimulating, and affordable places to leave their kids. For less than one dollar a day — a comparable price to other day cares — parents can drop off their infants and toddlers at a Kidogo center, where skilled caretakers lead structured play and learning activities. “You enter one of our centers after walking through the slums, past awful smells and poor infrastructure, and it’s like an oasis of happy, playful children,” says Habib, who adds that Kidogo also provides healthy meals and works closely with parents to teach them about nutrition and hygiene.

In addition to its own centers, the organization also runs a training program that helps owners of local day cares overhaul their businesses and brand them as Kidogo franchises. “They’re able to attract more clients and improve their profits,” says Habib. The owners, whom the organization calls “mamapreneurs,” are also taught financial literacy and how to make the most of limited resources. “We show them how to create toys from locally available recycled materials, like toilet-paper rolls and cartons,” Habib explains.

Between Kidogo’s three flagship centers and seventy-six locations run by mamapreneurs, the nonprofit serves almost two thousand children. Habib, who has collaborated with Columbia’s Tamer Center for Social Enterprise since earning her MPA at the School of International and Public Affairs, hopes to expand the organization throughout Kenya by 2021 and eventually to neighboring countries. “Our vision is to be the leading network of high-quality, affordable childcare centers in East Africa,” she says.

The farthest-reaching impacts of Kidogo’s work will materialize in years to come. “With childcare, you often don’t see the fruits of your labor until the kids are teenagers and adults, when they have better high-school completion rates and are more likely to go to college,” says Habib. “We’ll see the true benefits decades from now, when our Kidogo kids are contributing members of society and doing incredible things.”

This article appears in the Winter 2019-20 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "A World of Difference."