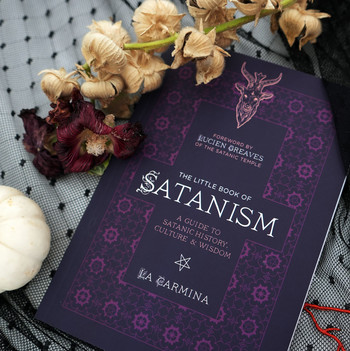

La Carmina, a graduate of Columbia College and Yale Law School, is an award-winning blogger, journalist, and author. Her most recent publication, The Little Book of Satanism, is a fascinating historical and cultural guide to Satanism and a spirited defense of the often-misunderstood religion.

Your book debunks a lot of common myths about Satanism. But perhaps the most important one to understand is that modern Satanists don’t actually worship the devil. If that’s so, what do Satanists believe?

Exactly right. There are many different kinds of Satanists, but most don’t actually believe in Satan and don’t worship him as either a god or as a force of evil. For the most part, Satanists are non-theists and view Satanism as a personal liberation from traditional theistic beliefs. We value nonconformity and revolt against the ideas of superstition and arbitrary authority. Modern Satanists are nonviolent and interested in the pursuit of reason, justice, and truth.

Why use Satan, then — certainly a controversial idea or figure?

Essentially, Satan is a metaphor. We believe in the historical idea of Lucifer as a light-bringer, a principled rebel angel willing to stand up against arbitrary rules or authority. In Western countries in particular, Christianity is so dominant. Many people who identify as Satanists were raised in religious, restrictive households and made to feel oppressed because they were different in some way. So by using Satan as a symbol, we’re taking that narrative back and making it our own.

How did you become interested in Satanism?

I’ve always been interested in gothic fashion and dark subcultures. When I moved from Vancouver to New York for college, my friends and I would hang out in the East Village, at places like the Pyramid Club, and see heavy metal. There’s a lot of overlap between those scenes and Satanism, so that was my first introduction.

After I graduated from law school, I decided not to practice and to focus on my work as a travel and fashion blogger, which gave me the opportunity to spend a lot of time in Japan. There’s a really vibrant and welcoming Satanic subculture there — which is notable in such a conformist society — and I started to understand more about those values. I found out that Satanists are not criminals or bad people; they’re just people pursuing their highest sense of self, and that idea was attractive to me.

in recent years, Satanists have engaged in activism around issues that I believe in, like reproductive rights and LGBTQ+ causes. As someone with a legal background, this side of Satanism really appealed to me.

One of the major tenets of Satanism is nonconformity. Is there a communal aspect, or would that be a contradiction?

Some people prefer to be lone wolves, and probably more so in Satanism than in other groups. But I think that for the most part, people do feel a sense of community. Many Satanic groups host community events — things like charity drives and beach cleanups, as well as online gatherings. People find strength in being with other people that share their values, even if that value is nonconformity.

Your book chronicles some of the major periods when Satanism has been used as a scapegoat for societal problems. Do you think we’re in such a panic now?

Throughout history, people have been unjustly persecuted, marginalized, and even hunted down and executed for being different. During periods of religious fervor, anyone who didn’t fit specific definitions of piousness were called devil worshipers. So yes, in a sense the Satanic Panic has never ended. We are still living in a society with tremendous theocratic influence, which dictates both laws and culture, and there are still very common misconceptions around Satanism. But modern Satanism is flourishing, with a renewed emphasis on charitable work and activism, and I’m optimistic about its future.

Most people imagine the devil as a red creature with horns and a pointed tail. But in your book you describe the many other visual iterations of Satan over the centuries. If you were to dress as Satan for Halloween, which depiction would you choose?

I love this question! In researching the book, I found it so interesting to see how different groups depicted the devil through history and how those depictions reflected the values of those periods. In medieval times, they made him a scary beast who devoured sinners. During the Enlightenment, there was a much more sympathetic view of the devil, who was seen as a sort of rebel defying ecclesiastical rule, so he was often depicted as a classical muscled hero. Often Satan is depicted with goats or as a horned and hoofed figure — a reference to the Gospel of Matthew, which says that Jesus will separate the sheep from the goats on Judgment Day. But there have been many interpretations of that as well. In Japan, you’ll often see a cute, almost cuddly goat-headed Satan. That one might be my favorite — it opens conversations and challenges people’s expectations.