1. Faith in the system is fraying

“A healthy democracy is predicated on the electorate’s faith in the integrity of the voting system,” says Ester Fuchs, an expert in US elections and the director of the Urban and Social Policy program at the School of International and Public Affairs. “The losers have to accept the outcome of an election and in the period between elections have to be willing to abide by the laws and the decisions of those who are elected. When the system is threatened — which is to say, when large numbers of people feel alienated or think that the system is rigged or that it’s not legitimate — you’re really threatening the foundation of democratic governance.”

For Fuchs, one of the major flaws in the voting system can be found in the Constitution itself: the Electoral College. In this much-maligned process, each state gets a share of 538 electoral votes, according to its number of senators and representatives in Congress. New York, for instance, has twenty-seven congressional districts, plus two senators, for a total of twenty-nine electoral votes. (Washington, DC, thanks to the Twenty-third Amendment, gets three.) The electors, handpicked by their state’s parties, pledge to cast their ballots for their party’s candidate. In most states, the winner of the popular vote gets all the state’s electoral votes. The candidate who nets a 270-vote majority becomes president.

“Interestingly, the founders put the Electoral College in place to take power away from the populace,” says Fuchs, who sits on the faculty steering committee of the Eric H. Holder Jr. Initiative for Civil and Political Rights, an undergraduate program that recently held events on the state of voting in the US. “In the early version of the Electoral College, electors were supposed to be independent — they didn’t have to follow the popular vote.” Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 68, wrote that this flexibility “affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

“But over time,” Fuchs says, “it became an accepted view that the Electoral College electors would be bound by the popular vote in each state, and would reflect it. So while in theory you might have a situation in which the popular vote does not reflect the electoral-vote victory, it would be like a hundred-year storm.

“Except that we just had Gore vs. Bush in 2000 and Clinton vs. Trump in 2016. Bush lost the popular vote, and Trump lost the popular vote. Once you win a state by 51 percent, that’s as good as winning by 98 percent, and the difference between the 98 and the 51 is lost in the national calculation. Votes are diluted in the presidential election because all those people beyond the 51 percent in each state are not counted.”

Until the 2000 election, the public never paid much attention to the Electoral College, Fuchs says, because the numbers usually worked out: not since the nineteenth century — in 1876 and 1888 — had the popular-vote winner not prevailed. “But now that we’ve had these recent discrepancies, it’s just another area where people see the system as rigged against them. If you keep having elections where the popular vote is not consistent with the Electoral College vote, from a democratic-governance point of view, it’s a problem, and it’s dire.”

To abolish the Electoral College would take a constitutional amendment — a dim prospect, Fuchs says. “Because our politics is now so rabidly partisan and divided, and because each party is looking for leverage within legal and institutional arrangements, it will be more and more difficult to fix this. The small states and the rural states benefit from the status quo — why would they give up this system, when doing so would help more-populous places like California and New York be more fairly represented?”

2. SCOTUS opened a Pandora's box

The 1965 Voting Rights Act was a watershed in US history, outlawing repressive tactics, such as literacy tests, long used against Black voters in the American South. Section 5 of the act required localities with a history of voter suppression to submit any changes to their voting laws to a federal court for approval, a process called preclearance.

Decades later, some people felt that preclearance rules had become an onerous relic that unjustly targeted jurisdictions for their past misdeeds. A legal challenge to preclearance in Alabama reached the Supreme Court in 2013 as Shelby County v. Holder. In a landmark 5–4 ruling, the Supreme Court effectively gutted Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act by declaring unconstitutional the formula used to determine what jurisdictions required oversight. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts concluded that states were being discriminated against based on past behavior, and that “nearly 50 years later, things have changed dramatically.”

“Within days of that Supreme Court decision, the states started passing laws,” says journalism professor and New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb, who is the director of the Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights and a faculty adviser for the Holder initiative. “Legislators were waiting on the Shelby County decision to introduce the new bills.” Texas, one of fifteen states released from preclearance, promptly announced a “very restrictive voter-ID law in which a handgun license would be accepted at the polling place but not a college ID,” Cobb says. “The thinking was that this would favor Republicans.”

Shortly after Shelby County v. Holder, North Carolina passed House Bill 589, a series of restrictions aimed at voter ID and early voting. While crafting the bill, an aide to the Republican House speaker wrote an e-mail to the board of elections asking for “a breakdown, by race, of those registered voters in your database that do not have a driver’s license number.”

The North Carolina NAACP sued the state, and in July 2016, a federal appeals court declared that the North Carolina law targeted Black voters “with almost surgical precision” and struck down HB 589. The court observed that the bill excluded many of the photo IDs used by African-Americans and “retained only the kinds of IDs that white North Carolinians were more likely to possess.” Despite this legal setback, Cobb notes, North Carolina pursued other changes to the voting system: reducing the number of sites for early voting (popular among African-Americans) and challenging thousands of voter registrations on the basis of a single piece of mail returned to the post office. Four days before the 2016 election, a federal judge ruled that North Carolina had illegally purged some 6,700 voters and ordered the state to restore them to the lists.

But the early-voting restrictions took a toll. “Black Turnout Down in North Carolina After Cuts to Early Voting,” NBC News reported on November 7, 2016, the day before the presidential election. In the end, Donald Trump won the state that Barack Obama ’83CC carried in 2008.

“North Carolina is widely seen by conservatives and liberals as a laboratory for what the future of voter rights might look like,” Cobb says. “The demographics of the electorate in the coming years is the main battlefront in politics right now.”

3. States are purging their voter roles

“The idea behind purging is to keep the voting rolls relatively consistent with who’s actually around to vote,” says Columbia Law School professor Richard Briffault ’74CC, who studies state and local-government law. “People die and people move, and those are the legitimate grounds for taking people off the rolls. But we don’t have a well-organized, integrated system for advising local polling places of these changes.”

Some states have seized on the purported problem of rampant voter fraud — “millions and millions of people,” as President Trump has often charged, who impersonate dead or ineligible voters whose names remain on the rolls — as justification for sweeping new measures, like voter purges. But the claim of voter fraud is itself fraudulent: numerous studies have found virtually none at all. (A 2014 Loyola Law School study estimates a fraud rate of one incident per thirty-two million ballots cast, and the Washington Post found only four documented cases in the entire 2016 presidential election.)

For Briffault, the voter-fraud myth is especially pernicious because it’s a distraction from actual threats.

“Fraud is more likely to occur on the inside, through manipulations of the vote-counting machinery and absentee ballots,” he says. “Ballot security is the issue. Voter fraud is not. Yet all the rules we’re seeing around voter ID and purging pertain to in-person fraud — which is basically nonexistent.”

In Ohio, lawmakers came up with a method to purge the rolls. “If you don’t vote during a two-year period, you receive a prepaid return postcard from the state, asking if you are still registered and if you are still at the same address,” Briffault says. “You can check yes or no and return it. Or you can do nothing. And there’s evidence that most people do nothing. If you don’t vote in the next four years and don’t return the postcard, you’re going to be purged.”

In 2015, Larry Harmon, a Navy veteran from Akron, went to vote and found he had been dropped from the rolls. An off-and-on voter who had sat out elections for various reasons, Harmon claimed he had a right not to vote, and that having not voted in the past shouldn’t prevent him from voting now. He sued the state. The US Supreme Court heard the case and handed down its decision this June.

“It was technically a statutory case about whether what Ohio did was consistent with the federal guidelines,” says Briffault. “The case wasn’t litigated on grounds of whether Ohio intended to suppress certain voters.”

By a 5–4 decision, the court upheld Ohio’s law. “The majority said the state could reasonably treat this as evidence that someone has moved,” Briffault says. “Justice Breyer’s dissent said that most people simply fail to return the postcard, and that unless you have other evidence that someone has died or moved, you shouldn’t be able to purge them.” Justice Sotomayor, in a separate dissent, wrote that day-to-day obstacles make it more difficult for “many minority, low-income, disabled, homeless, and veteran voters to cast a ballot or return a notice,” though the matter wasn’t raised in this case.

Briffault thinks the issue of discrimination could be raised, however, in this or other cases, with regard to minorities (a 2016 Reuters analysis found that the purging of 144,000 voters in three Ohio counties had a disproportionate impact on Black communities), the disabled, or anyone who doesn’t vote regularly.

“Unfortunately, many people don’t vote, but in some elections they want to vote,” says Briffault. “In that sense, the Ohio law discriminates most against people who are only intermittently engaged.”

4. Gerrymandering isn't going away

After each census, states redraw their congressional-district lines to reflect changes in the population, with the goal of achieving numerical equality among districts. But when one party controls both legislative chambers in a state, lawmakers can carve up districts in ways that redound to their electoral benefit. This practice is known as gerrymandering.

While racial gerrymandering is prohibited by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and by the Voting Rights Act, partisan gerrymandering has been a legal gray area ever since Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry approved a redistricting map in 1812 that favored the incumbent Democratic-Republican Party over the Federalists, with critics noting that one particularly contorted district resembled a salamander.

“The Supreme Court has been going round and round on partisan gerrymandering,” says Briffault. “What they’ve said is that districting is so inherently political that it has been difficult to find principled criteria in the Constitution or constitutional law that the courts could use to distinguish what’s permissible from what’s impermissible.”

Gerrymandering is achieved in two ways, Briffault says: packing and cracking. “Packing is when districts are drawn in a way that concentrates huge numbers of voters from one party in just a few districts, while the rest of that party’s voters are stretched out as relatively powerless minorities in the other districts. Cracking is when you take evenly divided areas and fragment them to the advantage of one party.”

This spring, the Supreme Court, in Gill v. Whitford, ruled on a redistricting plan in Wisconsin that Democrats claimed made it hard for them to win a fair share of seats.

“Wisconsin is evenly divided politically between Republicans and Democrats, but because of packing, Democrats win fewer districts by wider margins — 80–20 or 90–10 — while Republicans win more districts by narrower margins,” Briffault says. “There are no 90 percent Republican districts.

“The claim in Gill v. Whitford was that the Republican-controlled state legislature diluted the Democratic vote and maximized the number of districts Republicans would likely control — and that this violates the guarantee of equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment.”

The Supreme Court, in a 9–0 decision, held that the Wisconsin Democrats who brought the suit had failed to show they were personally affected by the gerrymanders. “The court didn’t rule out that partisanship could be the basis of overturning a gerrymander. But you still have to show that you, as an individual voter, were directly affected, and the Wisconsin case has been sent back to the lower courts to explore that.

“So the matter has been kicked down the road, and we’re not really any further along than we were before,” says Briffault. “The issue remains live.”

The Supreme Court has been going “round and round” on the issue.

5. Cybersecurity: it's not just hacking

“When most people think of cybersecurity risks in elections, they focus on the voting machines,” says Jason Healey, a senior research scholar at SIPA specializing in cyber-conflict. “But if you’re a hacker, the electronic voting machines are very difficult to affect on a wide scale: every county has a different system, and the machines aren’t necessarily connected to the Internet. You might be able to affect voting machines in a particular district, and while that might be damaging, it’d be really tough to produce a large-scale effect.”

Healey, a US Air Force Academy graduate with a liberal-arts degree from Johns Hopkins, was director for Cyber Infrastructure Protection at the White House from 2003 to 2005. He says the most vulnerable components of the election system are the ones responsible for voter registration (“those are just Microsoft systems connected to the Internet; you can do a lot there”) and vote tabulation (“the Russians have affected vote tabulations in Ukraine — why hack the voting machine when you can hack the tabulation database?”).

A state’s voter-registration database “is probably the biggest vulnerability,” says Steven Bellovin ’72CC, a Columbia computer-science professor who lectures on the security risks of electronic voting systems. The registration database provides a large “attack surface,” he says, since local authorities need to access it from all over the state. “Hackers can delete or alter records, or steal personal information to use for targeted propaganda.”

Like Healey, Bellovin isn’t too worried about a national election being hacked, and advocates paper-based systems to insure against irregularities. In New York City, the paper ballots that are fed into the tabulating machines can be recounted by hand in the event of a dispute.

But that’s not the case everywhere. “After the problems in Florida in the 2000 presidential election — the famous recount with the hanging chads — the Help America Vote Act was passed by Congress to help states upgrade antiquated voting systems,” says Bellovin, who served as a technical adviser on the US Election Assistance Commission, which grew out of the Help America Vote Act. “Unfortunately, many jurisdictions installed computerized voting systems. Computer scientists have long been opposed to this. No computer scientist trusts computerized voting systems. They’re just not secure enough. Across the country, people are casting votes on these electronic voting machines that leave no paper trails.”

Bellovin is “much more worried about computer error — buggy code — than cyberattacks,” he says. “There have been inexplicable errors in some voting machines. It’s a really hard problem to deal with. It’s not like, say, an ATM system, where they print out a log of every transaction and take pictures, and there’s a record. In voting you need voter privacy — you can’t keep logs — and there’s no mechanism for redoing your election if you find a security problem later.”

Healey believes that if you have a good election system, you should be able to go back and, if necessary, recreate the votes cast. The problem, he says, is that the mere suspicion of tampering can shake the confidence of the electorate. “In the end it’s about trust in the electoral system. That’s front and center, especially now.”

6. Reality is under attack

In the hours after the 2016 presidential election, Jonathan Albright, who is now research director for Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, was thinking about all the disinformation that had circulated on the Internet during the campaign — what he calls “arguably the most powerful propaganda machine in the history of US election politics.”

Albright wanted to know how this propaganda spread. How were the websites connected? What did these networks look like? Albright fired up his laptop and went on a data-gathering binge that broke the “fake news” story wide open. With a mix of journalistic sleuthing, social-scientific analysis, and computational ingenuity, he mapped the flow of deceptive data as it moved through social media — Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Google — to the personalized home pages of YouTube. He discovered a vast “influence network” of dubious sources pumping out click-friendly, viral-ready messages that formed an “ecosystem of real-time propaganda.” Studying 306 fake-news sites, he found that they contained more than a million hyperlinks, suggesting an exponential scope far greater than previously understood, with content being shared billions of times.

While the threat of this data-bombing is evident, the actual fallout is nearly impossible to assess. “Surveys have repeatedly proven to be imprecise in measuring the effects of certain ads on people’s voting behavior,” Albright says. “I’m not sure if we’ll ever be able to go back and empirically quantify what effect these millions of different messages had on each neighborhood or family group in 2016. It’s very difficult.”

This past July, a federal grand jury in the Justice Department’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election indicted thirteen Russian nationals for their work with the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Kremlin-linked “troll factory” based in St. Petersburg that Albright had helped expose. According to the indictment, the IRA set up hundreds of Facebook accounts and bought thousands of ads designed to exploit social divisions, stoke anger, and, ultimately, damage Hillary Clinton and help Donald Trump.

Albright says these attacks are evolving as trolls adapt their tactics to a shifting digital landscape. “In 2016 we saw meme-focused and outrage-focused messaging” — politically charged posts on issues like immigration, which infiltrators used to track the responses of Facebook users and compile data on them. “But in 2018,” Albright says, “the strategy is more participation-based: there’s a push to create confrontations that are public and visible.” He points to bogus Facebook groups like Resisters (whose page has since been deleted), which plugged an event urging opponents of US immigration policy to “take over” the headquarters of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “There’s a push to integrate into existing events and then either collect information on the participants or promote the event to groups further out on the fringe.”

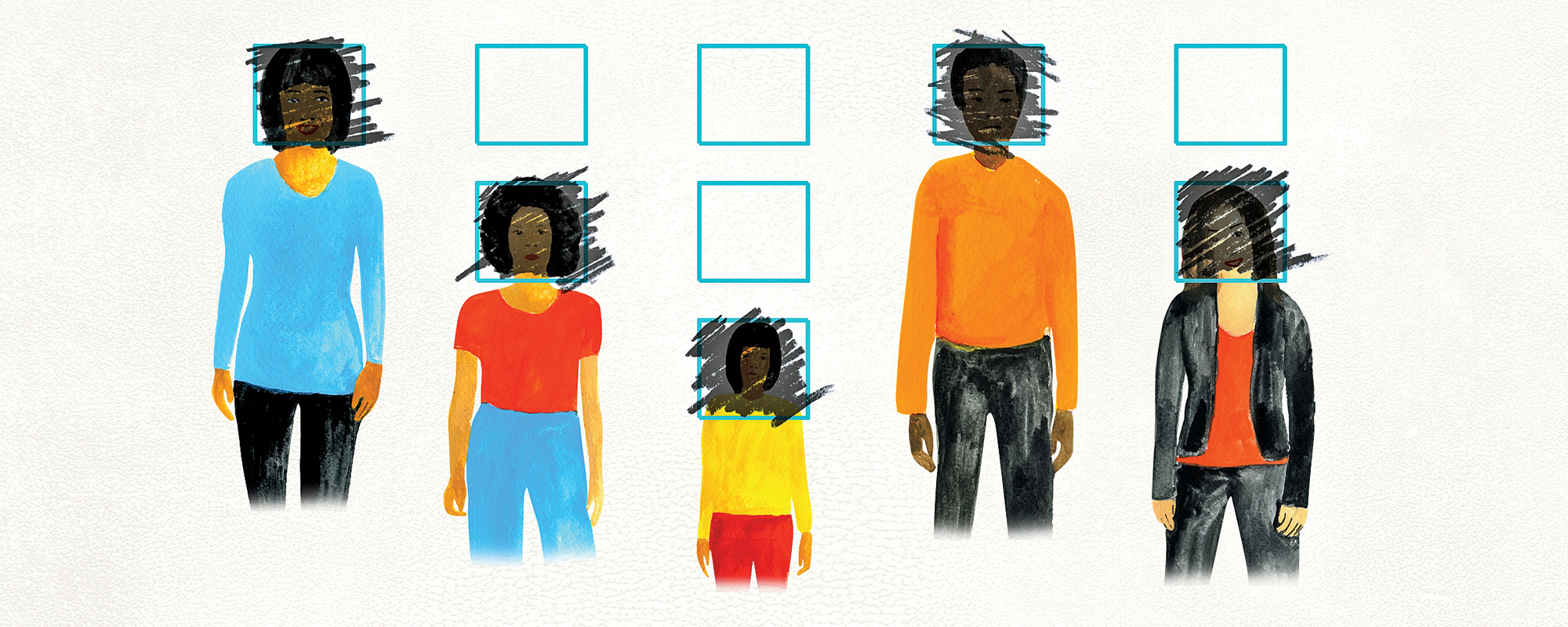

Albright has also untangled the IRA’s targeting of certain audiences with messages “meant to sow distrust in institutions, including voting systems,” he says. “In the last few years there was a lot of effort aimed at African-American voters and younger urban audiences to dissolve trust in the integrity of voting systems and in the process of voting itself — creating the perception that your vote doesn’t matter, that the system is rigged.”

While social-media companies have taken steps to filter out the fake from the real — an exceedingly demanding task — Albright believes that what needs to be understood and addressed most are the sources of fake news and the phenomena that drive online traffic. And he warns that this battle over reality will only get more complicated as technology advances and becomes more available.

“We are quickly moving into an era where the ability to edit images or videos — even to change faces — is going to improve so much,” he says, “that you won’t be able to trust anything.”

There’s nothing in our Constitution that says it should be hard for people to vote.

7. The 2020 census needs our full attention

Every ten years, as required by the US Constitution, the federal government counts the residents of the country. This survey, or census, provides the base population number from which the 435 seats of the House of Representatives are apportioned, and by which legislative boundaries are redrawn.

But according to SIPA professor Kenneth Prewitt, who directed the US Census Bureau from 1998 to 2001, this essential tool of American democracy is in serious trouble.

“It’s hard enough to do a census in a big country,” Prewitt says. “But at this point in preparing for the 2020 census, the fundamental operations are understaffed, underfunded, and performing less well than they were in 2000 and 2010. In 2000, knowing the response rate had been falling over the century, we invested in an ad campaign as well as a major partnership effort with churches, chambers of commerce, local schools, and so forth. This is not happening now at the scale needed.”

But Prewitt’s biggest concern is the addition of a controversial question.

In March, the US Department of Commerce, which administers the census, announced that it would be introducing a new question about citizenship. Prewitt worries that the climate of fear around immigration will suppress the response, with many people less likely to be forthcoming to the inquiring, clipboard-holding government employee at the door — “and there’s little the Census Bureau can do to fix that.”

In June, five immigrants’ rights groups sued the Commerce Department, claiming that a citizenship question would result in undercounts, with a loss of representation and federal funds for necessities such as transportation and education. In July, a federal judge allowed the suit to go forward, chiding the Trump administration for a “strong showing of bad faith.”

“This gets even more complicated,” says Prewitt. “Don’t forget: the 2020 census takes place smack in the middle of what could be one of the nastiest elections in recent history. The interaction between the census and the election will shape the census experience, and, if it’s not handled well, the census could easily feed a very unpleasant political environment.

“If it appears that the census is being used by the administration to strengthen its constituency and not count the people it doesn’t think ought to be counted — if brown people aren’t going to get the attention they deserve and are going to be left out of the census, whether it’s by design or the result of operational deficiencies — it’s going to be a story that will feed into white nationalism.”

The census was enshrined at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, including its infamous Three-Fifths Compromise, which permitted states to count a slave as three-fifths of a person. For decades, this particularly rewarded the South in congressional seats and Electoral College votes. Over time, however, the census evolved into a vital, nonpartisan democratic instrument — and, for Prewitt, a source of civic pride. “You really get a picture of the country, and I came back with a deep respect for how complicated the country is,” he says of his time as director. “It was a very positive experience. That’s what I worry about in 2020: will it be positive for people? Will they take pride in responding to it? You want to make it a celebration of the country. Will it feel like a celebration in 2020?

“The census is part of our democracy and our Constitution. The framers were conscious that if you live in this country, if you work and pay taxes, you have certain rights, including a right to representation, and you don’t have to be a citizen. To challenge this undermines what the census has always meant.

“Nothing is worse for me than having a census that seems to have partisan goals, because if the census doesn’t float above partisanship, then nothing does. The whole idea of civic responsibility just washes away.”

8. Voter engagement is the answer

“We need to make it easier for people to register. We need to make it easier for people to vote. We need to make it easier for people to access information about candidates,” says Ester Fuchs. “There’s nothing in our Constitution that says it should be hard for people to vote. The idea of a democracy is that we want to engage as many people as possible.”

Fuchs believes that the fundamental fairness of the voting process has been eroded. “You have these legal barriers being put up, like voter-ID laws, which make it harder for people to register and to vote; you have court cases that have exacerbated the inequality in the election system; and you have the problem of gerrymandering. And that’s apart from Russian intervention in the elections and the president actually calling into question the legitimacy of institutions in this country, including the free press.

“In order for a democracy to work, you want to create a system that is as fair as possible, that the public views as fair. Without that, a democracy cannot sustain itself. I think that democratic governance in the US is really on the edge of crisis.”

And yet Fuchs, who calls herself a “pragmatic utopian,” is hopeful. A believer in Tip O’Neill’s adage that “all politics is local,” Fuchs says that solutions must come from the ground up. In 2012, with her former student William von Mueffling ’90CC, ’95BUS, she started a not-for-profit website and mobile app for New York City voters called Who’s on the Ballot, which provides a district- and citywide listing of the candidates, with links to their campaign websites and Twitter feeds, as well as election schedules and polling-place information. Run through SIPA, the project is one of the ways that Fuchs wants to educate the electorate.

“Education campaigns are crucial. We need to put civics back into eighth-grade education. Few people understand how elections work or how a bill becomes a law or how government impacts their lives. The way to get people engaged is to get them to understand that government decisions affect their day-to-day lives, and that there’s something at stake if they don’t participate.”

She also thinks the current political turmoil, despite the gloom and despair of large swaths of the electorate, could fertilize the democratic soil.

“To the extent that insurgent candidates can raise money online, to the extent that young people and especially young women are willing to run for public office, this will energize people,” Fuchs says. “They’ll see themselves in the political process again. They’ll decide that there’s a reason to engage.”