“Do not write like an academic,” says science journalist Claudia Dreifus. “Do not write like a businessperson. Do not write like a policy person. We’re going to teach you how to write like a journalist.” Dreifus has taught her course Writing About Global Science for the International Media for the past seventeen years, mainly at the School of Professional Studies. A former science writer for The New York Times, Dreifus believes that science literacy is essential to a healthy democracy. And having found long ago that most scientists have trouble making themselves understood to nonexperts, she decided to create a journalism course for science and sustainability students — one of the first such courses in the nation.

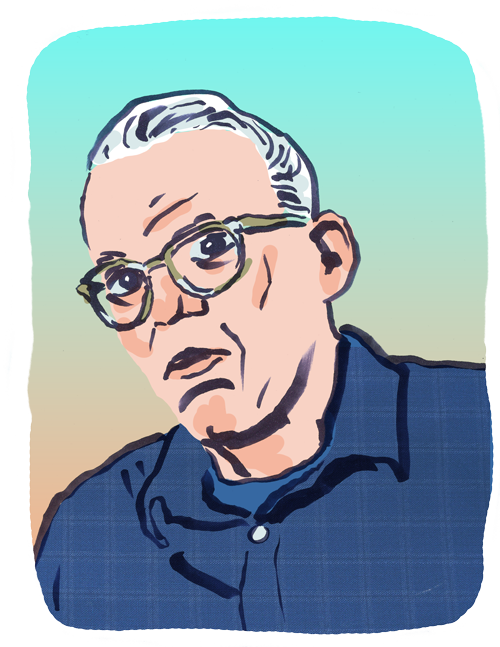

To supplement the class, Dreifus also started a series, open to the public, called Creator’s Night, in which she speaks with science-focused journalists, editors, and artists, giving students a chance to ask questions, meet people, and with any luck get an article placed in the Times or a video posted on Scientific American’s website. On a recent Friday in Uris Hall, Dreifus hosted a talk with New Yorker writer and climate activist Bill McKibben, whose nineteen books, she says, are “models of what effective science communication can be.” McKibben, wearing a blue shirt and an SPS-issued olive baseball cap, was promoting his latest book, Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization, and shared his Twain-like mix of humor, social criticism, and plain American horse sense.

“We’ve got a period of years — numbered, if we’re lucky, on the fingers of both hands — to make huge progress,” said McKibben, framing the climate crisis in terms of possibility rather than doom. As the cofounder of 350, a global climate nonprofit working to “end the fossil-fuel era,” McKibben has lately turned his attention to that cheap, limitless energy source burning reliably above. “Ninety percent of new energy generation around the world last year came from the sun,” he said. But in the US, a dark cloud is blocking the light of progress — the country is “trying to squeeze the last dollars out of the fossil-fuel industry,” including coal (“subsidizing eighteenth-century technology is almost too comical for words were it not also tragic”). McKibben sees America’s retreat from solar as wrongheaded and mind-bogglingly self-defeating: “If you were setting up to destroy the economic and technological future of the United States and with it its political influence around the world, you would do exactly the things that we have decided to do on energy.”

But he has also found silver linings. “One of the reasons that I’m now writing as much about clean energy as I am about climate is because it’s actually much easier to get people to have that conversation,” he said. “Turns out that people like solar power across a wide variety of ideologies.” McKibben described his part of rural Vermont as dotted with houses with “Trump flags on the mailbox and solar panels on the roof.”

Yes, China has taken command of the solar market, he said, but the difference between buying oil and buying solar panels is that with oil, you burn it and have to buy more, whereas with the panels, you buy them once, and then you “don’t depend on the Chinese. You depend on the sun, which heretofore has come up each morning.”

Not that solar is perfect: McKibben acknowledged the environmental impact of mining the metals — mainly lithium — to make grid-scale solar batteries (“mining is always a scourge on the planet”), but he emphasized that renewable energy requires far less extraction than fossil fuels, and he expressed excitement over the boom in non-lithium battery technology. As for the lower costs, he lauded an initiative in solar-forward Australia that will provide three free hours of electricity for citizens every afternoon. “There’s been a lot of academic talk about abundance and affordability,” McKibben said. “That’s what abundance actually looks like in practice.”

McKibben’s audience included Dreifus’s students as well as people from other SPS programs and the climate school. “Bill has the secret sauce,” Dreifus told them. “He manages to make the very difficult interesting.”

It’s a skill that Dreifus, who received the 2023 Dean’s Excellence Award for teaching, strives to help her students develop. Not that she wants them to abandon academese entirely: “We’re going to teach you how to write like a journalist, but we don’t want you to fail your other courses,” she says. “When you’re in the academic mode, you write their way. But here, you park it outside the door.”

This article appears in the Winter 2025-26 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Let the Sunshine In."