If you’ve fallen for an online scam or hack recently, you’re far from alone. Experts say that both the volume and sophistication of online attacks are surging as cybercriminals learn to exploit the latest artificial intelligence tools. How do these new scams work, and how can you protect yourself? For answers, Columbia Magazine recently spoke to Asaf Cidon, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science who studies how cybercriminals use technology.

First, can you tell us about the research you do?

My team works with cybersecurity firms to analyze the types of attacks that their customers are experiencing, with the goal of developing better defenses. A lot of our research has focused on phishing schemes, where you’ll get an email purporting to be from a trusted source, like your bank or credit card company, asking you to type in your credentials for the purpose of stealing your money or identity. Phishing emails and texts fail to trick most people, but they’re cheap to produce and can be blasted out in huge waves, so they’re still profitable.

My colleagues and I have also done a lot of work on “business email compromise” attacks, or BECs, which are a bit more sophisticated. This is when someone receives an email that seems to be from a coworker, typically a superior, instructing them to do something nefarious. The classic case is a CFO will get an email that appears to be from their CEO telling them to quickly wire money to a supplier. The account they’re told to send the money to belongs to a criminal organization, of course. These attacks are more expensive to orchestrate because the criminals will often infiltrate a company’s computer networks and do reconnaissance first, assessing its reporting lines, finances, and ongoing business deals, so that the email they send to the victim seems plausible. BECs cost US companies billions of dollars a year.

You published a paper last summer showing how phishing schemes and BECs are evolving as a result of AI.

Yes, my team worked with the California-based cybersecurity firm Barracuda Networks to analyze millions of fraudulent emails that its customers received from early 2022 to April 2025, with the goal of understanding how AI is influencing the content of the emails and the tactics that fraudsters are using. It was the first large academic study ever conducted on the topic. We found that cybercriminals, as of last spring, were using AI mainly to improve their writing. Their emails were no longer filled with typos and awkward phrases; instead, they often contained polished, professional-sounding English. This likely enabled them to evade spam filters and fool more people. We didn’t find evidence that scammers had yet begun to employ entirely new forms of trickery using AI. But we suspect they may be doing so now, and that a dangerous new era of cybercrime is around the corner.

Tell us more.

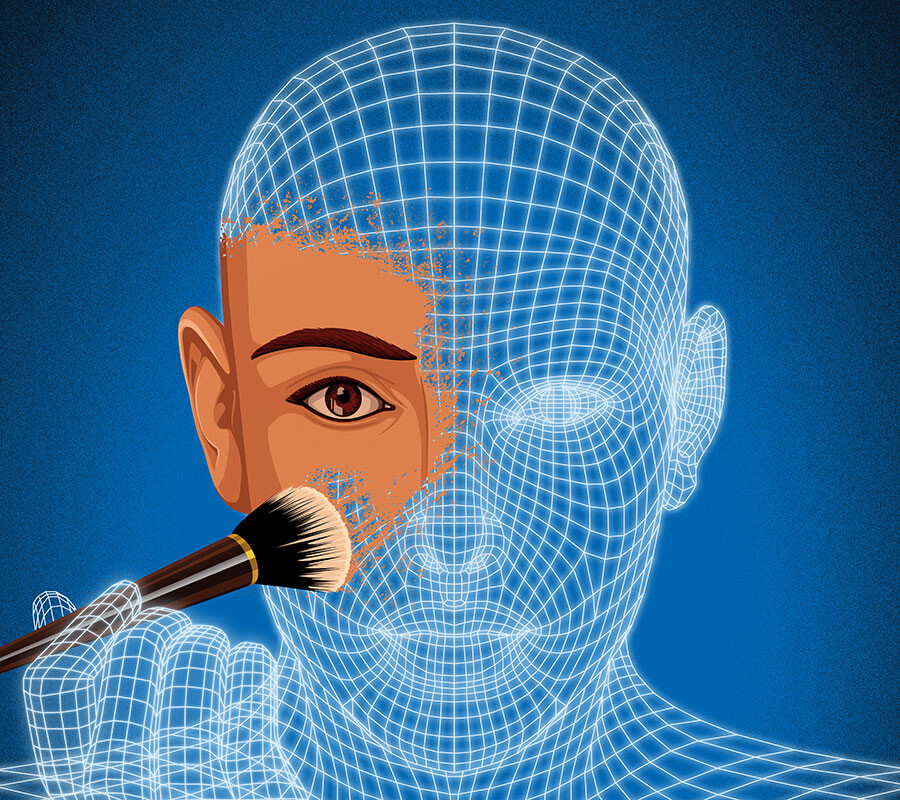

Well, AI has evolved incredibly quickly over the past year, in ways that are concerning. Today, using freely available technology, I can take a short video clip of you speaking — downloaded from YouTube or your social media, say — and feed it into an AI model that will generate a deepfake video that looks and sounds almost exactly like you. I could then call your friends, family members, or coworkers and interact with them in real time, using a text-to-voice interface, so that they think they’re talking to you. Or I could generate a voice clone for making phone calls. A few months ago, this technology wasn’t very good. Today, it’s quite realistic. This is what worries me and everyone else in my field.

That’s terrifying. Is there evidence that criminals are launching deepfake attacks?

There have been reports, mostly anecdotal, that suggest they’re starting to use these tools. It’s hard to know how widespread the attacks are, though, because reliable, up-to-date statistics about trends in cybercrime aren’t publicly available. There are no centralized sources of information on the topic. Most of the relevant data is owned by big tech companies and their customers, and victims of online attacks are often too embarrassed to report them to authorities. My research group and others are now trying to figure out how to collect data on deepfake video or audio attacks so that we can assess what’s actually happening.

Who is most vulnerable?

Typically, when cybercriminals adopt new technologies, they’ll initially roll them out in high-end attacks that justify the additional time and investment required. I suspect they’ll do the same thing here. So, you can imagine that the type of scams I described earlier, where a company’s financial officer gets a scam message from their boss, could incorporate a deepfake video or audio.

Consumers have been targeted with similar “imposter” scams in the past, but it’s less common. For example, when someone is about to make a down payment on a home, they might get a message from a person claiming to be the escrow agent, telling them to wire the payment to a criminal account. The criminals, in those cases, might have infiltrated the realtor’s computers to learn homebuyers’ names.

There’s also what’s called the “grandparent scam,” where someone calls an older person pretending to be their grandchild, saying they’re in trouble and need money. If an AI-generated clone of the grandchild’s voice were to be used, it would obviously be more dangerous.

What can be done to combat this?

I think we’ll find technological solutions. That’s the good news. Machine-learning tools that my team has developed may provide a starting point. We’ve shown that AI models trained to analyze email copy and metadata together can effectively spot phishing schemes, for example. The same principle could be applied to voice or video calls. A defensive AI system would consider: What phone number or IP address is the call coming in from? Is it a familiar or unknown one? Is the caller discussing finances and using pleading, cajoling, or intimidating language? It should be possible to design a tool that detects these types of clues and provides you an alert or warning. The challenge will be creating something that is cost-effective and which technology companies can afford to run routinely, on all of your voice or video calls. That could take a few years. In the meantime, we’re going to be in a vulnerable phase.

It sounds like we should look out for the same types of clues that an AI detector would consider.

Absolutely. If I get a phone call from a random number next week, and my wife comes on the line and pleads with me to immediately wire her money, I’m going to insist on calling her back on a different number. People have also proposed having a secret codeword that’s shared amongst your family members, in order to signal that it’s really you.

What else should we be doing to protect ourselves against online fraud, in general?

You must use multi-factor authentication when accessing your accounts. It’s super annoying, but you have to do it. It’s more critical now than ever. Another option is purchasing a hardware token, which plugs into your device to verify your identity. It’s easier than multi-factor authentication and slightly more secure. And either change your passwords regularly or use a password manager. Apple and Google now have free password managers that are pretty good.

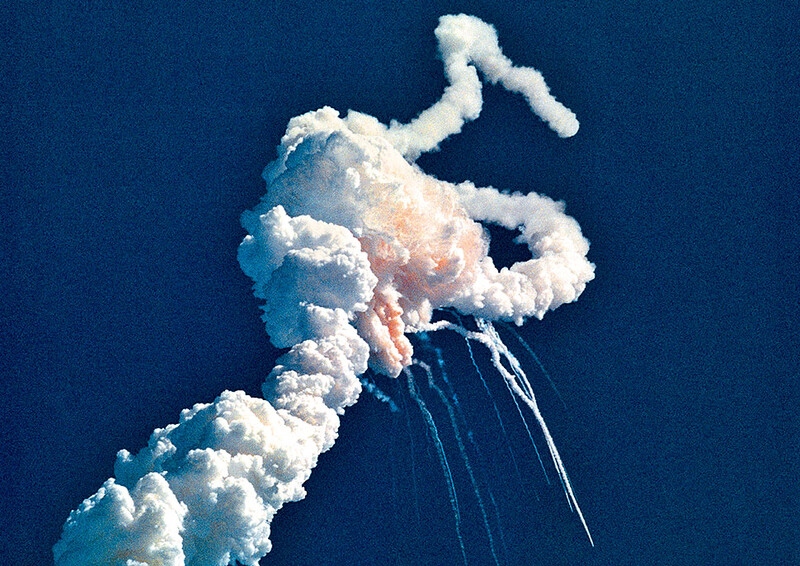

Don’t assume this can’t happen to you. Everyone is vulnerable, no matter how smart or educated you are. I know fellow scientists and professors who’ve fallen for online scams, and I’ve come close myself. Cybercriminals use tactics that exploit our emotions, making us feel that we must act quickly or else something bad is going to happen to us. In those moments, our natural impulse to get along with people and avoid confrontation works against us. It may feel awkward to say to a relative or colleague, “Hey, is this really you? What’s our codeword? Can we hang up and connect another way, just to be safe?” But that could soon be a normal part of life.