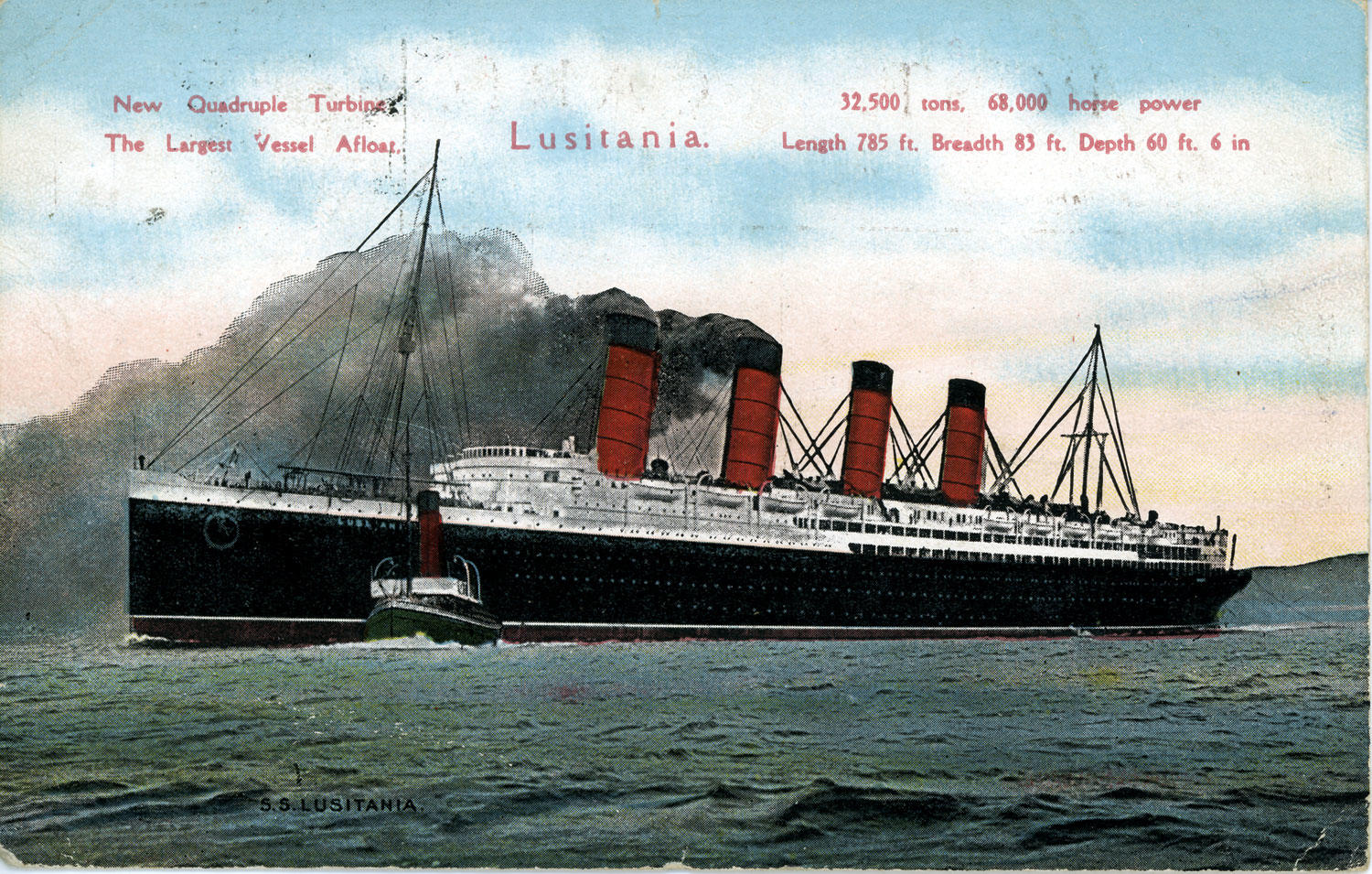

When it comes to epic disasters involving luxury liners, the Titanic and its iceberg loom large. Few are as familiar with the Lusitania, another ill-fated transatlantic cruiser, which left New York on May 1, 1915, with great pomp and celebration, only to be torpedoed by a German U-boat in hostile waters off the coast of Ireland. The Lusitania, once called by its owners “the safest boat on the sea,” sank in just eighteen minutes. Of the 1,959 passengers and crew aboard, 764 survived.

In Dead Wake, Erik Larson ’78JRN seeks to detail the last crossing of the Lusitania and “the myriad forces, large and achingly small, that converged one lovely day in May 1915 to produce a tragedy of monumental scale.” Using the testimony and diaries of survivors, along with telegrams, letters, and secret intelligence ledgers, Larson constructs his compelling narrative with a painstaking — some might even say pathological — attention to historical accuracy.

While lesser writers might feel constrained by the responsibility to remain faithful to primary sources, hard evidence, and the rigors of science (yes, we are given a thorough grounding in torpedo technology), Larson revels in the challenge. Indeed, he has already demonstrated his total mastery of the art of re-creating history in all its lurid and lucid detail in earlier books, including The Devil in the White City and In the Garden of Beasts. Both won him critical acclaim and an international fan base.

Dead Wake is a complex work: Larson weaves together several plotlines and characters to share multiple perspectives on the central event. The story shifts effortlessly from the point of view of William Thomas Turner, the capable captain of the Lusitania, to that of U-boat pilot Walther Schwieger, a man known for his kindness, humor, and love of puppies. We get an unusual glimpse into the private life of President Woodrow Wilson, who, in the spring of 1915, seems more preoccupied with a budding romance than with events in Europe. And we go behind the scenes at the British Admiralty, where, ten months into the war, petty infighting is beginning to undermine naval intelligence.

As Larson sets the stage for the disaster, he underscores its brutality by giving us a peek into the private lives of dozens of the Lusitania’s passengers. We are introduced to a feminist architect with a passion for spiritualism, a young couple traveling with their six children, and a rare-book dealer whose luggage includes more than a hundred illustrations by the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. Below decks, we meet several crew members, including eighteen-year-old Leslie Morton and his brother Cliff, two apprentice seamen who are returning home to England to fight in the war. As we come to know and care about each of these living, breathing souls, the ineluctable reality of their impending ordeal and poor odds of survival becomes increasingly oppressive.

The book’s tension is heightened by the fact that, despite the German government’s warning that all ships entering the war zone are “liable to destruction,” the Lusitania’s passengers and the American public blithely underestimate the threat. “That the war had begun at all was a dark amazement, for it had seemed to come from nowhere,” writes Larson. He points out that American isolationism is so acute that on June 27, 1914, the day before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, the American newspapers seem only vaguely aware of European tensions. In a wry aside, he notes that the New York Times’ lead story that day was “Columbia University at last winning the intercollegiate rowing regatta, after nineteen years of failure.”

Dead Wake may be a work of nonfiction, but it has all the freshness, immediacy, and dramatic tension of a contemporary thriller or spy novel. Indeed, Larson conjures this sad chapter of maritime history in a way that both illuminates and leaves us demanding more. After finishing Dead Wake, readers will find themselves devouring Larson’s copious footnotes, googling photographs of the Lusitania, and poring over vintage film clips of the liner as it leaves New York on its final, fateful voyage. In those flickering black-and-white images, passengers arrive at the dock full of excitement and anticipation. They smile for the camera, gather their luggage, and stand on deck waving white handkerchiefs as the ship slowly pulls away from the harbor. That Erik Larson has so successfully rescued these unlucky people from anonymity makes those last goodbyes all the harder.