In the spring of 1949, Joan Fischer bought her six-year-old brother Bobby a plastic chess set at a candy store on their block. Bobby’s main opponent was his mother, and each time he beat her, he would turn the board around, play her side, then beat her again. “Since Bobby couldn’t find a worthy opponent, or any opponent for that matter,” writes Frank Brady in his new biography, “he made himself his principal adversary. Setting up the men on his tiny board, he’d play game after game alone, first assuming the white side and then spinning the board around . . . ‘Eventually I would checkmate the other guy,’ he chuckled when he described the experience years later.”

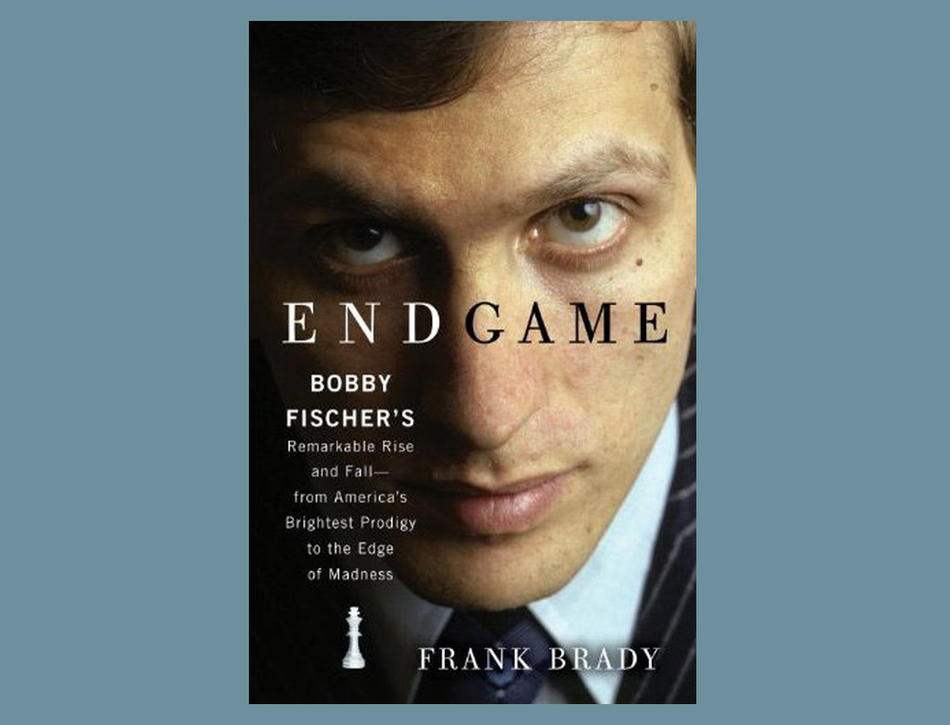

The lonely child in a Brooklyn apartment brilliantly playing two sides of the same board, and making himself his own “principal adversary” is one of many telling images in Endgame: Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall — from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness. Two distinct Bobbys stand out in the public memory. One is the genius, a chess player of the highest caliber who brought new life to the ancient game. The other is the madman, the hate-spewing international fugitive. Where these two sides intersect is of particular interest to readers who seek the real Fischer.

Their guide is Frank Brady ’76SOA, a former professor of journalism at Barnard and now a professor of communication arts at St. John’s University, the founding editor of Chess Life magazine, and the president of Manhattan’s Marshall Chess Club, where a teenage Fischer played his “Game of the Century” in October 1956. Fischer’s unusual display of daring and instinct, including ingenious sacrifices of his knight and queen, earned the battle its nickname.

In that match, the 13-year-old Fischer defeated 26-year-old Donald Byrne, a Penn State professor of English and the 1953 U.S. Open Chess Champion. “It was as though [Fischer had] been peering through a narrow lens and the aperture began to widen to take in the entire landscape in a kind of efflorescent illumination,” writes Brady. “He wasn’t absolutely certain he could see the full consequences of allowing Byrne to take his queen, but he plunged ahead, nevertheless.”

Brady knew Fischer from the time Fischer was a child, played games against him, ate dinner and took walks with him during the “on” times in their on-and-off friendship. From this relationship the author is able to fill in many missing details from his subject’s highly unusual life. A few months before the Byrne match, for example, Fischer was invited to join the eccentric neo-Nazi millionaire E. Forry Laucks and his Log Cabin Chess Club on a 3500-mile road trip to Havana. Bobby’s single mother, Regina, a travel-hungry intellectual, radical, and endlessly fascinating character (who warrants more space in the book than Brady is able to give), insisted on tagging along. Rounding out the party were two other chess-playing walk-ons: Norman T. Whitaker, a con man, pedophile, and disbarred lawyer who once falsely claimed to know the whereabouts of the kidnapped Lindbergh baby, and Glenn T. Hartleb, a bespectacled chess expert from Florida who greeted everyone he met “by bowing low and saying with deep reverence, Master!” Here, as throughout Endgame, Brady approaches the odd facts of Fischer’s life with the measured patience of the historian and the eye and ear of the novelist.

In the summer of 1972, at 29, Fischer faced the defending world champion, the Soviet Union’s Boris Spassky, in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik. After 21 games, and with millions watching around the world, Fischer defeated Spassky 12½ to 8½ to become World Chess Champion. Fischer’s performance also brought chess into the spotlight in America — a considerable feat in itself. During the tournament, televisions in New York City bars were tuned to chess instead of to baseball. Chess sets sold out in department stores, and, as Fischer himself put it, the game was “all over the front pages” in a country where it had long been of interest to only a quiet few.

Timing and circumstance had a lot to do with Fischer’s celebrity outside the chess world. It was the middle of the Cold War, and beating the Soviets, who had for decades dominated international chess, became for Americans a matter of national pride. While his role as the American challenger made him an underdog, Fischer did not play the part well. His arrival (on a plane stocked with oranges, so that juice might be “squeezed in front of him”) was delayed by squabbles over money, and once he got to Reykjavik, he delayed the games with tantrums about distracting television cameras and lights. Fischer’s success became such a topic of geopolitical interest that Henry Kissinger telephoned — twice — to urge him to quit the antics and play the game. In the atmosphere of paranoia and accusation that lingered, Fischer believed for most of his adult life that the Soviets were plotting to kill him.

As a biographer, Brady is better placed than anyone to relate how Fischer’s genius warped into madness, but he resists this kind of analysis, being more concerned with persuading us that the Fischer who ranted against the Jews and applauded the September 11 attacks should also be remembered as a player of considerable grace. Brady is also remarkably adept at making both the mechanics and the beauty of chess understandable to the novice, and at making chess seem important and worthy to one who might otherwise have no interest in the game. He opens his book with a quote from the novelist A. S. Byatt, about a young chess player who saw movements across the board as beautiful lines of light. Brady, too, sees chess as a game and an art — and sees Fischer, then, as an artist.

While Brady’s passion for the game is one of his strengths, the reader at times can feel bogged down in long, consecutive descriptions of tournaments. It’s not that the various matches are hard to grasp, it’s that they are easy to forget, and so the reader might find it difficult to understand Fischer’s overall progress. The book both suffers and benefits from Brady’s enormous amount of research. Narrative transitions are occasionally buried under an overload of information.

It is the rare firsthand accounts from Bobby and those who loved him that provide the most affecting moments in the book. Chief among them is a 1973 letter from Regina to her son, in which she warns, “The greater the person’s mind and talent, the greater the destruction . . . Don’t let millions of people down who regard you as a genius and an example to themselves. It’s no joke to be in your position.”

Anyone who reads Endgame will know how right she was.