The human spirit, when pushing the limits, is often spurred by intelligent purpose. But sometimes gross folly works just as well. This is manifest in Britain’s 19th-century quest for the Northwest Passage.

The passage, a shortcut water route between the Atlantic and the Pacific around the top of North America, which navigators assumed must exist, obsessed explorers ever since Columbus found the Americas rudely blocking the way from Europe to Asia. The English made a specialty of looking for it, and the Canadian Arctic is dotted with the names of seagoing Elizabethans: John Davis, William Baffin, Martin Frobisher, Humphrey Gilbert, and Henry Hudson, who lost his life in the great bay that bears his name after his crew mutinied rather than proceed farther. He was only the first of many Europeans to find that along the route to the passage there was often a terminal detour.

All this we learn from Anthony Brandt ’61GSAS, who skillfully tells the complex tales in The Man Who Ate His Boots: The Tragic History of the Search for the Northwest Passage. Brandt, the editor of the National Geographic Society Press Adventure Classics series, tells us especially about the 19th-century English missions — varying parts of madness and gallantry.

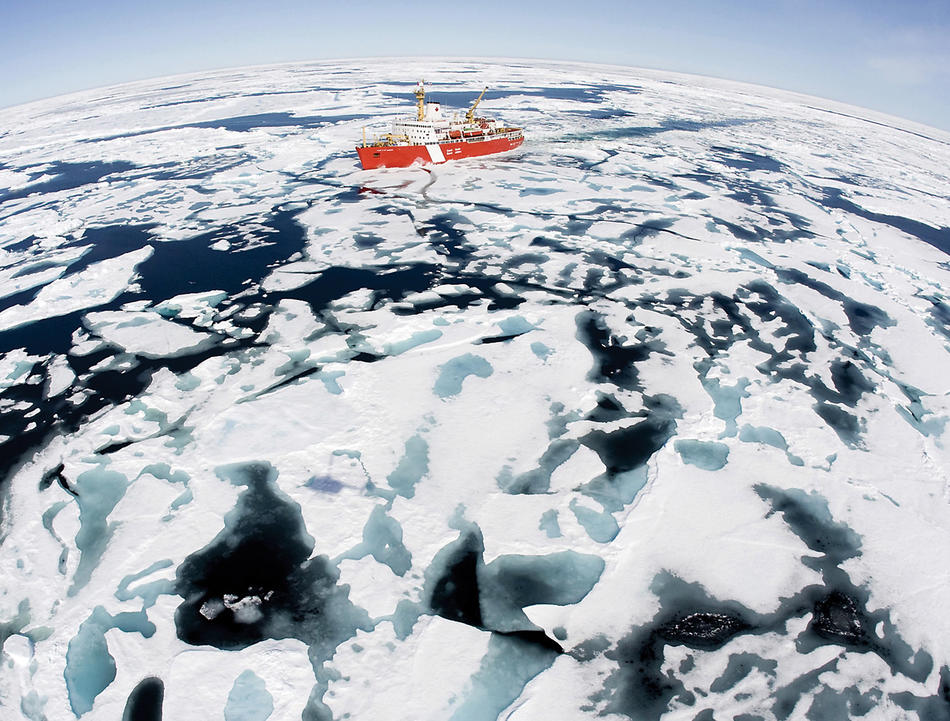

The drama was played out in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, some 36,000 islands north of the Canadian mainland. The majority are tiny and uninhabited; the largest loom implausibly over the mainland when viewed through the distortions of a Mercator projection. West of Hudson Bay, most of the water around the islands is frozen all year.

John Barrow — in effect the executive vice president of the Royal Navy from 1804 to 1845 — was the commanding figure who made finding the Northwest Passage a British fixation. He gave the Royal Navy a new role post-Waterloo by sending expedition after expedition to the Arctic. Early failures did not discourage Barrow, who believed that open sea water did not freeze and that ice formed only on coasts. The top of the world was covered by water with a thin rim of ice, he insisted: Find the weak spot and crash through to Asia.

Barrow’s project culminated in the lost 1845–48 mission of Sir John Franklin, the boot-eater of the book’s title, who, with his men, had been reduced to eating shoe leather two decades earlier on his first attempt.

Barrow’s successors commissioned a series of rescue expeditions, first after Franklin’s party and then after their remains. These were intermittent — both for exploration and rescue — financed by others, including the Hudson’s Bay Company and Franklin’s indomitable second wife Jane. It was on one of these, led by Robert McClure from 1850 to 1854, that the passage was found, though it was frozen shut and had to be crossed by sledge. McClure was honored for the discovery, but the Crimean War had begun, shifting the interest of the public and the Royal Navy to other regions.

No one actually sailed the passage until Norway’s Roald Amundsen took three seasons to do it, starting in 1903. (Amundsen was the man who in 1911 reached the South Pole.) In 1944 a Canadian police ship made it through in a single season.

But this was all in the future for Barrow’s explorers. The challenge they confronted was made to order for a people who had kept the sun from setting on their empire. The longer the search for the passage failed, the more it became a Forlorn Hope — that is, the impossible task that English gentlemen routinely accepted and generally achieved, often with a knighthood or a peerage to follow. The English gentleman might not always achieve a Forlorn Hope, but where he failed none was likely to succeed. Barrow’s men frequently encountered Indians, most often the Inuit, and they seemed to have found them not bad chaps, for savages. One group of these, very short of rations themselves, turned over most of their food to a starving band of Englishmen specifically because the Inuit were much better at doing without. It did not seem to occur to the English that the Inuit had survived for centuries in the Arctic and had mastered traveling light. English parties traveled very well equipped, and sometimes died hauling their impedimenta.

Brandt tells all this with sure narrative control and admirable clarity. He has a good instinct for character, including that of the Inuit, but particularly that of Franklin, the kindly commander who literally could not kill a mosquito; he told the astonished Inuit that the mosquito had as much right to live as he. Franklin was corpulent, genial, and brave, going back for one more try at the passage at an age when he was entitled to a peaceful retirement at Bournemouth or some other unfrozen harbor. He took 128 others with him to a death that eventually included “the last dread alternative,” which is to say cannibalism, although that happened after he had passed beyond command.

Brandt relates this astonishing account about as well as anyone is likely to, but he is not without minor fault. He is inclined to supply unneeded details about members of the British royal family, and get them wrong. He reports, for example, that the explorer William Edward Parry was much lionized by high society and was invited to dinner by Queen Victoria’s father, one Prince Leopold, and that Victoria told Parry that she had read all his books. As it happens, Victoria’s father was named Edward and had been dead for seven years at the time of the dinner; Victoria was all of eight. Prince Leopold was Victoria’s uncle — the future Leopold I of Belgium — and the Princess Victoria of Brandt’s account was not the future queen but her mother, Leopold’s sister Victoria. Brandt also persists in calling Franklin’s second wife Jane “Lady Jane”; it should be Lady Franklin.

Lately, climate change has taken a hand in the fortunes of the passage. For several years it has been open two months for cruise ships, among other vessels. This year, the season ran into September. On present trends, the passage may become all that Sir John Barrow could have wished, and having become practical, it is now a bone of contention. (Canada regards it as part of its internal waterways, as if it were the Saint Lawrence. The United States and other maritime nations beg to differ.)

Brandt is a global warming pessimist. “Perhaps by the end of this century,” he writes, “ice will have vanished from the world altogether.” If he is right, there will come a generation of readers for whom his tales of frigid heroism and folly will seem more fantasy than history.