It was a cold morning in the fall of 2015, and I was running in Central Park. As I passed by people, trees, and benches, all a blur of colors, something leaped out to me in sharp focus: two men holding hands.

I had seen men holding hands before, but there was an intimate quality about that couple, or about that moment, that slowed me down. I remember walking back to my apartment on the Upper West Side knowing that something inside me had shifted.

Men holding men. Women holding women. The way they looked at each other. Smiled at each other. It was all around me, and it was all I saw for several days. On the streets and in the subway, in parks, cafés, museums, restaurants, and takeout joints, as well as on campus, they blended effortlessly into the New York City landscape. But I noticed them.

I was thirty years old. I had recently graduated from Columbia Journalism School, and I was working as a writing fellow at Nautilus, a hip science magazine, which had just won two National Magazine Awards. While the fellowship made me a better journalist, coming to Columbia and the city of New York altered the course of my personal life. Completely.

I was raised Hindu and grew up in the city of Aligarh, located southeast of New Delhi in one of India’s poorest states, Uttar Pradesh. Aligarh is famous for both its padlock-manufacturing industry and its scholars. Aligarh Muslim University is considered one of India’s highest seats of learning. The university was born out of the Aligarh movement, a late-nineteenth-century reform initiative that helped establish a modern educational system for Muslims in India, where they are a minority. Although Aligarh has seen its share of clashes between Hindus and Muslims, religious differences didn’t have an impact on my everyday life. My best friends were and are Muslims, as were most of my teachers.

I lived with my homemaker mother, accountant father, and studious younger sister in a rented room that barely accommodated a twin bed, two chairs, a table, and three storage boxes — one big and two small. Every night my parents would set the table over the big box to make space for them to sleep on the floor. My sister and I shared the bed. By the time I was fifteen, my father, who worked two jobs, had saved enough to buy a one-bedroom apartment built by the government for low-income families.

At first I didn’t feel different from other kids until people around me implied I was different. I was in seventh grade when a male teacher asked me why I chatted with the girls instead of playing cricket with the boys during sports class. “It doesn’t look good,” the teacher told me. So I forced myself to play with boys and hated it. In ninth grade I auditioned for a fashion show at my school and was laughed at for the way I walked — “like a girl,” students teased. “Don’t move your hands so much while talking,” friends advised. I was already called beech ka (somebody who is in the middle) or hijra (the name for intersex or transgender people).

Once on the school bus, a tall guy whom I secretly liked stood in the aisle and began flirting with the girl I was sitting with. Gesturing toward me, he asked, “Is he a boy or girl or both? There is only one way to check,” he said, pointing at my crotch. They laughed. I stared at my feet.

I hated the way I was. I might have been fifteen or sixteen then. There was nobody like me and no one I could talk to about how I felt. When no amount of praying to God to make me the same as other boys helped, I decided to take charge. I would wake up at 5:00 a.m., go to the terrace, and practice walking like a man. Back straight. Chest out. Hands by your side. Make sure your waist doesn’t sway. It felt wooden. To remind myself, I started keeping slips of paper that read, Walk like a man. I would look at them throughout the day. It didn’t work. I just couldn’t change. So I decided to try to excel in high school and then in my undergraduate studies in zoology, hoping I would be noticed more for my grades and that the bullying would stop. It worked for a time. Then one night the college seniors threw a party. They played a game in which they showed movie titles on a screen and we had to guess which title matched which student. After a couple of matches, Mrs. Doubtfire flashed on the screen. All heads turned to me. Almost everyone laughed. In that moment, I realized that none of my attempts to conceal my true self had worked.

In college I had a strange friendship with a guy. We would hang out long after class, and I would make excuses at home to sleep over in his room. The cuddles in bed soon became exploration of each other’s bodies in the dark of the night. We never spoke a word. In the morning, we would pretend that nothing had happened. Pretense was an easy escape.

I knew there were words like “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual,” and “homosexual,” but I never let myself ask if I was one of them — as if just saying those words would make me one. It was 2007, and anyone in India who had intercourse with a person of the same sex was a criminal and could be imprisoned for life. But I didn’t care what the law said, because the culture around me had reminded me enough that LGBTQ people were other people. I wanted to be mainstream.

After college I left Aligarh and began my career as a journalist at a newspaper in Jaipur, in western India. A year later I moved to New Delhi to work at an environmental magazine. My colleagues at both places were progressive and kind. They noticed my mannerisms but never called me names, which was a relief. But I still didn’t feel safe enough to share my turmoil about my sexuality with them. I assumed they were all heterosexual. They didn’t talk about gender or sexuality. I now realize why it is crucial to have diverse schools and workplaces and to have discussions about diversity, sexuality, gender, and harassment. You have to see people like you being treated equally in order to feel that you are normal.

In 2009, the Delhi High Court decriminalized gay sex. Some LGBTQ people celebrated. I didn’t. In my mind, I wasn’t one of them.

I thought if I could love a woman, everything would be fine. I met some wonderful women through friends, but nothing lasted until I saw Swara (not her real name) in my office. I felt drawn to her, so I asked her out and we started dating. A part of me genuinely wanted to succeed in loving her, but she would often tell me that she felt like there was a wall between us that she couldn’t climb. That made me sad. We went on a vacation, and I told myself I would do everything I could to make her feel loved. I don’t know if I was doing it for her or for myself. When a voice inside me said I should kiss her, I did. When that voice said I should hold her, I did. Swara probably sensed the half-realness of it. She was deeply perceptive. She was also the only person who confronted me. “Do you like men?” she asked me a couple of weeks later over dinner. I covered my fear with a fake smile and said, “No, what are you saying?” I lied to her. And to myself.

In 2013, I applied to Columbia Journalism School. I felt that a more global perspective and new skills could help me tell better stories about health and the environment in India. That year, the Indian Supreme Court overturned the Delhi High Court order and re-criminalized gay sex. Although I rarely came across reports of gay people being arrested, I knew that they lived in constant fear. It was a lot safer to live a lie.

I was accepted to Columbia. Although I got partial funding, securing the remaining money was stressful. I had no savings. To help, my father decided to take out a massive loan by remortgaging his house. I told my parents about Swara and that I planned to marry her. Two days before flying to New York, I went to meet Swara’s parents. I sat across from her father and told him that I would marry his daughter after I finished my course at Columbia. When I left their house, I asked myself — why did I do that?

In the fall of 2014, I landed in New York City. I moved into Columbia housing on Riverside Drive. The pace of the city was fast. People had tremendous energy. Everyone in my international cohort of science journalists was brilliant and accomplished. I had chosen to study science journalism because I felt my stories lacked scientific rigor, and I didn’t know how to write about science in a way that my readers could connect with on a personal level. At Columbia I fell in love with the beauty and darkness of science.

I didn’t think much about Swara. She wrote me e-mails saying that she felt she was losing me. I assured her that we would be together soon. In my mind I held on to the idea that I would marry her.

After school I got two fellowships that allowed me to stay in New York for another year. That’s when I decided to explore the city. I think when I saw those two men holding hands in Central Park I was ready to see them. Over the next days and weeks, as I continued to notice the free expressions of gender and sexuality around me, I slowly began to permit myself to face my feelings. I decided to go to a gay bar in Hell’s Kitchen. I stood across the street and took out my phone, pretending to be on a call while watching beautiful men go in and out of the bar. I couldn’t muster the courage to enter. I took the train back uptown.

I did this once more before telling myself that I had to honor my feelings. As I stood outside the bar, I could hear my heart pounding. But when I went inside, a smile stretched across my face. The music was loud, but I was at peace.

I went there every other weekend. I started telling my New York friends, “I think I like men.” And every one of them responded with a version of “That’s great, Ankur. I’m happy for you.” Some of them even came with me to the bar. But I still wasn’t comfortable identifying with a particular type of sexuality. In late 2015 I flew to India to attend my sister’s wedding. In Delhi I met Swara and instantly felt like an impostor. That night I lay awake next to her in her apartment, thinking, I don’t want to be a fraud. The next day, I told her that I thought I liked men. She looked strangely composed and asked, “Are you sure?” I told her I wanted to figure it out for myself. I invited her to my sister’s wedding, but she didn’t come. I texted her, saying that I was very, very sorry for lying. Many days later, she texted me back, wanting to know why I’d done this to her. I couldn’t say anything more than repeating that I was sorry.

When I returned to New York, my body felt lighter. I wanted to learn more about sexuality, so I started working on a feature story for Nautilus. I had several questions, such as, if I feel naturally attracted to men, why do I watch heterosexual porn? Why do I still like to flirt with women? Over several conversations with developmental psychologists, sociologists, and sexual-rights experts, I found a label that I felt comfortable with: “mostly gay.” I wrote a feature about sexual fluidity (when your sexual orientation changes over time), but I didn’t identify as sexually fluid myself. I started coming out to more friends, professors, and editors. And every time I did, I felt more confident and happier.

I went on dating apps and met interesting men who identified in many different ways. I was amazed at the range of their experiences and the openness with which they talked about their lives. I had conversations about gender, sex, architecture, education, food, and family. Before, the people around me made me suppress my sexual identity. In New York the people around me eased my coming-out process. I learned how cultures shape so much of what a person can and does become.

In mid–2016 I returned to New Delhi. By then, Swara was happily married to another man. I started coming out to my friends. Although my sexuality was a crime then, I had this urge to tell, to speak my truth. Coming out is not a one-time thing. It’s a process that people need to do over and over again, probably to solidify something — a new identity, perhaps — or to tell the world that they exist. Most people immediately accepted me. Some took time. I started meeting Indian men through dating apps. Most were not out. Some were married, some had kids, and some said they would marry a woman but were meeting men to fill a void inside them.

My parents were desperate for me to get married, because by Indian standards their thirty-one-year-old son had already crossed the marriageable age. I decided to come out to my sister first. I knew she’d accept me. Her response was, “You do what makes you happy. Be with a man or not. But don’t ruin any woman’s life.” So one night in Aligarh I sat down with my parents, and with much hesitation I said, “I don’t like girls.” They looked confused. Then in a roundabout way I said, “What’s wrong if I spend my life with a man?” My mom said, “Men are friends, not life partners.” But my father saw what I was getting at. He told me that he didn’t approve of same-sex relationships, that it was shameful and embarrassing. “If you want to go on this path, do it after we die,” he said. They had given their verdict.

Meanwhile, after many frustrating dates, I met Karan. He is a Sikh. Because of him I know what love feels like. He believes in the power of honest conversation to sustain relationships. He made a rule: if we have an argument, we can’t go to bed until we talk it through. Karan was with me every minute in the fall of 2018, when my mother lost her long battle against cancer.

That was also the year the Indian Supreme Court struck down section 377. I was in New York, and my phone started buzzing with texts from friends congratulating me. I remember smiling, sitting in my bed, and replying, “Thank you.” This ruling was the result of a determined fight over several years by lawyers including Arundhati Katju ’17LAW and her partner, Columbia Law lecturer Menaka Guruswamy, who argued that section 377 of the Indian Penal Code criminalized the very existence of LGBTQ people by criminalizing their sexuality — an attribute that is as intrinsic to people as their race and gender. The Supreme Court ruling emphasized that LGBTQ people are constitutionally equal. Of course, Karan and I are happy that the law is on our side. But cultures change slowly. My father knows about the ruling, but he still doesn’t approve of my sexuality.

Karan and I live in New Delhi. We have a group of friends around whom we feel loved and safe. Still, there are very few places here where we can comfortably hold hands. When I travel around India, I almost always pretend to be heterosexual. Same-sex marriage is not recognized under Indian law, and we wonder what kind of future lies ahead for us in Delhi. Can we raise a child who wouldn’t have to constantly explain why she has two fathers? Under the government of Narendra Modi, Indian society is getting more polarized along lines of class, gender, and religion. My Muslim friends in Aligarh don’t feel safe. Muslims and people from marginalized castes get publicly lynched. Most mainstream media institutions no longer hold the government accountable. Hindu majoritarianism is rising.

In New Delhi I work as a freelance journalist. I also cofounded a journalism project called Land Conflict Watch, in which I work with a team of journalists and researchers who collect data about ongoing land disputes in India. I am out to my colleagues and talk to them about Karan. I do this consciously to send a message to those who are struggling to come out. I want them to know that this workspace is safe and equal.

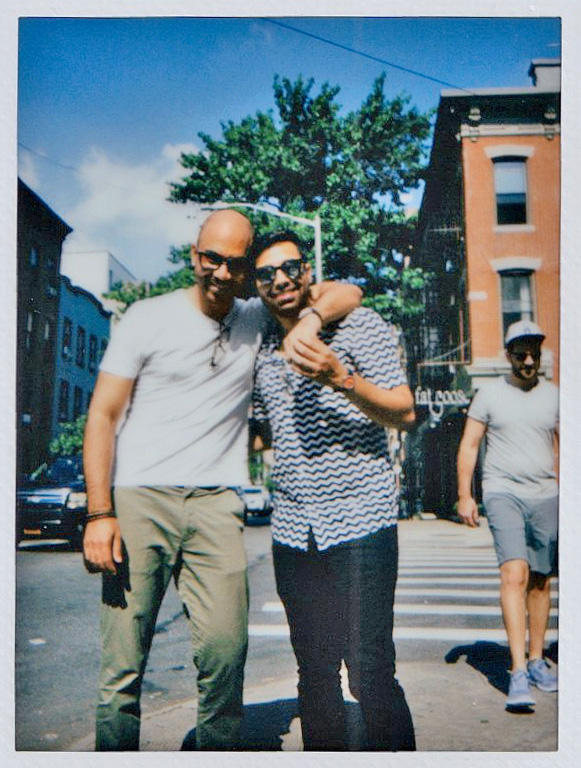

In the fall of 2018, I was in New York on a fellowship. Karan visited me there. One weekend I took him to the Columbia campus and showed him the journalism school. We sat on the Low Library steps by the statue of Alma Mater and ate five-dollar falafel with rice from a food truck on Broadway — my go-to meal when I was on a tight budget. Later, we walked to Central Park. The sun was setting behind the apartment towers on Central Park West, and the trees had taken on the yellows and oranges of fall. We stood still for a moment. Then I reached out and took Karan’s hand.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2020 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "The Laws of Love."