For all its gleaming glass and steel, 66 Rockwell Place, the new high-rise soaring 457 feet above the site formerly known as 29 Flatbush Avenue, is but one tall shoot in the bamboo thicket of apartment towers growing in Downtown Brooklyn. Thus the marketing challenge for its developer, the Dermot Company: how to distinguish this particular building and attract those $2,500-to-$6,000-a-month renters?

One could tout the “taupe linen tile” floors, “absolute black granite” countertops, and dinner-plate-sized showerheads. And of course there are the state-of-the-art health club, attended coffee bar, library, Zen garden with fire pit and waterfalls; lounge with chef’s kitchen, game room with pool tables, air hockey, and foosball; and the forty-second-floor Sky Lounge and rooftop sundeck, with drop-dead views.

That’s what the developer decided. “We wanted to create an opportunity for our residents to live surrounded by art,” says Andrew Levison, director of acquisitions and asset management at Dermot. “By giving young artists the opportunity to create works on the site, we hoped to establish an immersive and community-building experience.”

To run the project, Dermot turned to Phong Bui, publisher and editor of the Brooklyn Rail, a hip art-and-culture journal. Bui then enlisted his old friend and collaborator Tomas Vu-Daniel, artistic director of Columbia’s LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies, which promotes printmaking through education, production, and exhibitions. Vu-Daniel, whose own works have been displayed from Songzhuang, China, to Ludwigshafen, Germany, recruited seventeen present and former fellows of the Neiman Center and handed one floor’s hallway to each, to decorate as he or she saw fit. (He and Bui teamed up to do two floors themselves.)

“I said to the Dermot people, ‘You can’t tell us what to do, and we will not take suggestions from you, either,’” Vu-Daniel recalls. “And they were fine with it.”

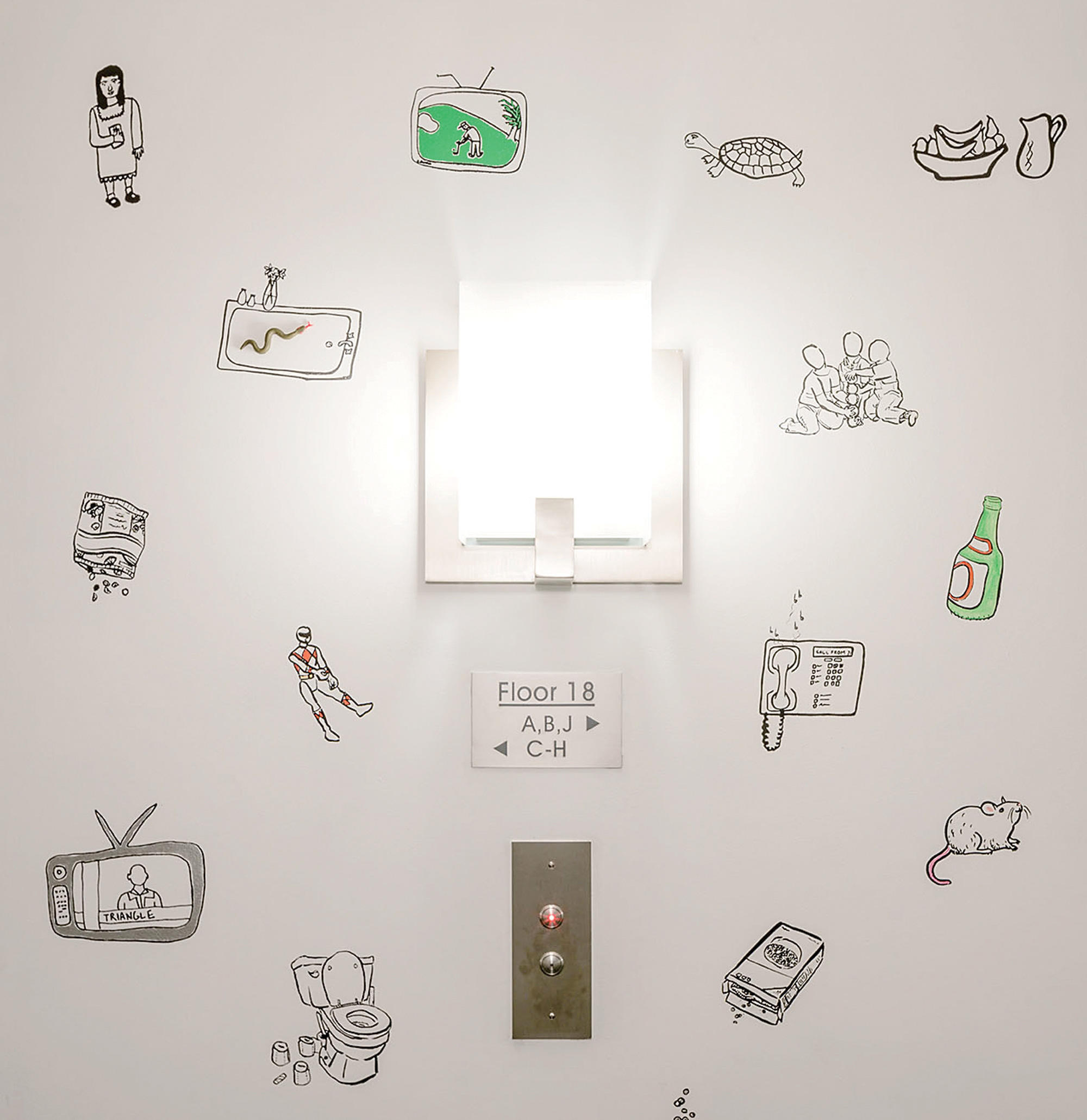

Unleashed on the dull green, seventy-foot corridors in January, the artists had made them their own by June. The results, collectively entitled Hallway Hijack, vary so widely as to defy general description: drawings, paintings, photos, and prints depicting toilets and teacups, dinosaurs with egg sandwiches, melting pigs. Nothing is anything you’d ever expect to see in an apartment building.

Jesse Weiss’s undulating Pepto-Bismol-pink forms on floor 31: are those hillsides or intestines? “I just kind of wanted it to be a desolate, stratified desert cross section,” says Weiss ’10SOA. “I was thinking about stratification of class, and the idea of people being stacked on top of each other.”

On floor 33, Xu Wang ’13SOA made a couple hundred line drawings of every kind of taxi, from moped to van to camel, then hung a carton of crayons on the wall. Residents (or visitors) have carefully colored in some, but have also added scribbles, snide comments, a stick figure of a person being struck by a car — all of it fine with Xu. “He’s one of these conceptual artists who really wants to interact with whoever is going to be interacting with his work,” explains Vu-Daniel. “The people who live here are allowed to do their own art interventions on top of ours. Relational aesthetics is where we’re at.”

Some residents even put the art to practical use. “When you get off the elevators, it’s sometimes confusing, because the elevators are on two sides of the hallway, so — which way’s my apartment?” says Amanda Daquila, thirty-three, a nonprofit program director. Fortunately, a bold tableau by Nathan Catlin ’12SOA on floor 21 portrays men on horseback chasing a fox from one end of the hall to the other. “The animals run toward my apartment, regardless of the side I get out on,” Daquila observes happily. “So I use that.”

Problem solved. But for how long? “I don’t think there’s a timeline,” says Vu-Daniel of Hallway Hijack. “What I’m hearing is they’re going to leave the art up — until it gets vandalized, or until the next project comes along, right?”