Bel Kaufman is seated in her long, light-filled Park Avenue apartment in what appears to be a white plastic outdoor chair, discussing the privileges that come with age. “I don’t do what I must do,” she says, “I do what I want to do.” Kaufman is wearing a beige blouse and light, neat makeup. Her hair is softly curled, her posture very straight. She wears sharp black flats — no orthopedics here. “Now, if I don’t want to do something, I say, ‘I’m sorry, no. I’m a hundred years old.’”

At one of three birthday parties given for her this year, Kaufman ’36GSAS graciously accepted her audience’s praise, but brushed aside the accomplishment of living a full century: “It must have happened when I wasn’t looking.” Kaufman still goes dancing every Thursday night, and a friend says her talent is in the mambo. She is working on her memoirs, but says that she hasn’t had much time to actually sit and write. Age can’t quite keep up with her pace, though she does sometimes misplace things in her files and “that wouldn’t have happened when I was 99.”

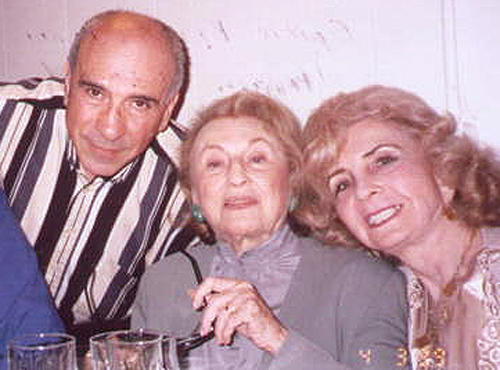

On the other hand, her personal files are extensive. Her apartment is filled with written material — letters, awards, and hundreds of books, including copies of Kaufman’s own 1965 best-selling novel, Up the Down Staircase, in several editions and languages. On a coffee table next to where she is seated is a book of photographs her children made for her.

Here is Bel at five, in Ukraine, sandwiched between her parents, the whole family wearing big fur hats. Here is her bright-eyed grandfather, the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, dressed as always, Kaufman says, in very dapper fashion. And here is Bel, older, windblown in a bathing suit with her son and daughter, and still many years away from becoming the well-coiffed and glamorous woman in her straight-backed plastic chair on Park Avenue (she says it’s better for her back).

This spring, Kaufman, while still only 99, became an adjunct professor at Hunter College, where she taught a course on Jewish humor. Not only is a sense of humor one of Kaufman’s defining personality traits, it’s also her latest and most personal academic interest: the study of humor as a means to survival. In other words, laughing in the face of something as serious as time might be exactly why she made it so far in the first place.

Kaufman’s course examines “why so many American comedians are Jewish, why so many Jewish jokes are self-accusing,” and why the resulting Jewish humor is a defense mechanism for survival. “Jewish humor,” she says, “is about beating adversity. Many Americans have absorbed that.”

When Kaufman immigrated to New York from Moscow at age 12, she entered the American school system with “not a word of English on my tongue,” and was placed in first grade. Her academic life improved from there. It’s funny: After graduating magna cum laude from Hunter in 1934 and earning a master’s in English literature from Columbia, after teaching hundreds of New York City schoolchildren and selling millions of books, after moving from Newark to Park Avenue and living to a hundred, Kaufman is still the oldest girl in the classroom.

When she looks back upon her own education, she recites Leigh Hunt’s “Jenny Kiss’d Me” (Time, you thief, who love to get / Sweets into your list, put that in!) and remembers two years spent at Columbia writing a thesis on London’s Grub Street, where in the 18th century “hack writers and gazetteers were like little mosquitoes flying around the big writers like Pope and Swift.” She rented a furnished room on Lexington Avenue from an Irish woman who told her, “boyfriends out at 10, steadies at 11.” (“So my boyfriends stayed ’til 10 and my steadies ’til 11.”) But she really lived in the stacks of what was, in 1935 and ’36, a brand-new library, later named Butler. “Those were very happy years.” She remembers her introduction to teaching with equal fondness, and says, “Do you know how I knew I wanted to be a teacher?

“At Hunter I had a friend who was taking an education course. They went out to a classroom to work with little children, elementary schoolers. She invited me to come take that class for one day. So, I came and I looked. There were all those eyes fixed on me, waiting. They were waiting! For something I had to give them. Something they would remember. It was an extraordinary feeling. And that’s how I feel now, at 100 years old, when I have an audience to give to.”

She adds: “You cannot teach a sense of humor, just like you cannot teach talent. But you can show students examples of good humor that arise from character.” One such example might be the work of her grandfather, who found in the darkness and oppression of shtetl life a reason to write funny stories that people loved. “I am now the only human being in the world,” Kaufman says, “who remembers Sholem Aleichem. I sat on his lap, I walked with him. He taught me to speak in rhymes.”

Or take Kaufman herself, who wrote Up the Down Staircase in a time of personal distress.

“I had just left my husband. My children were grown and in college, and my mother was dying of cancer in a hospital. It was a sad time, but I was able to write humor — just like Sholem Aleichem, who wrote humor on his deathbed.” Up the Down Staircase, based on Kaufman’s experiences teaching in New York City’s public schools, opened up the troubles of the urban classroom to an enormous audience. It was also a very funny book. “I had to rip up some of the funniest pages of the novel as I was typing them,” she remembers, “because my tears fell on them and made little blisters on the paper. I think what helped me survive was the ability to laugh.”

Kaufman says that if people come to listen to you, “you have to give them something that’s important and funny and serious.” So when questioned about a connection between education and humor, she asks if she should tell an intelligent Russian joke. Of course she should.

So somewhere in Russia, a man walks into a bar every day at three and orders two glasses of vodka. Eventually, the bartender asks, “Why not just order a double?” The man explains that he has a dear friend in Kamchatka, and each orders a drink for himself plus a drink for the other, and in that way they stay close though they are far apart. Then one day, the man walks in and orders just one vodka. The bartender says, “I fear that something has happened to your dear friend.”

“No, no!” the man replies. “It’s just that I’ve quit drinking.”