In late October of 1961, William Neal Brown ’50SW, a professor of social work at Rutgers, received an urgent telephone call from his friend Clyde Ferguson. Ferguson, a Rutgers law professor, had been scheduled to take part in a debate the following week on the Rutgers-Newark campus with Malcolm X, the fiery Black Muslim orator from Harlem. The topic was to be “Integration or Separation.”

But now, Ferguson told Brown confidentially, he would have to pull out. It seemed that Ferguson, who was serving as general counsel for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, and who would later become U.S. ambassador to Uganda, had received a call from the White House, advising him that if he appeared with Malcolm X his career in public service would be jeopardized. “I need a replacement, Neal,” Ferguson said. “I asked the students for ideas, and they all said, ‘Get Brown.’”

This vote of faith meant a lot to Brown. With no political aspirations of his own to protect, and with just days to prepare, he agreed to pinch-hit for Ferguson.

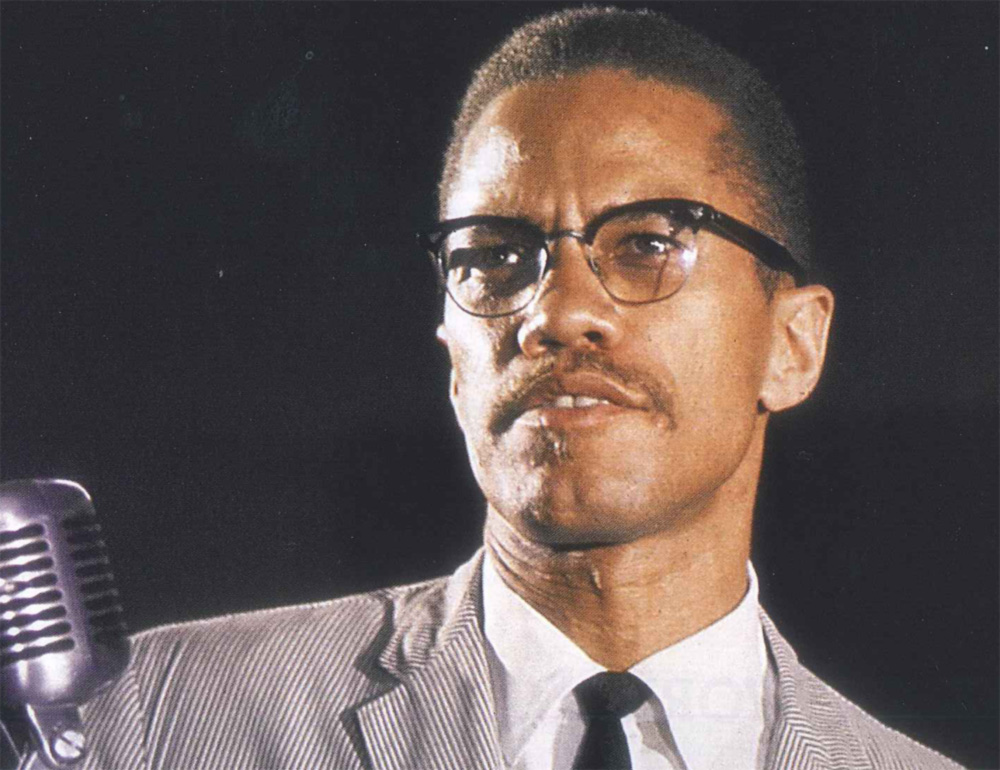

A fool’s errand, some said. Malcolm X — former street hustler and now national spokesman for the Nation of Islam — was a bold, forceful, deeply charismatic speaker with a piercing intellect and a reputation for demolishing his PhD’d opponents. In his furious indictment of racist white America and the “anemic” mainstream black leadership, Malcolm had tapped into something powerful in the psyche of poor and working-class blacks, and like any true revolutionary, he made his rivals seem hopelessly outdated.

But Neal Brown had reason to be confident. During his undergraduate days at Hampton Institute, the historically black college in Virginia, Brown was the star of the debating team, which had traveled the East Coast and gone head-to-head with the teams at Harvard and Yale.

“I became a really big man on campus,” he said recently in his home in Millburn, New Jersey. “The debating team got as much support as the football team.”

Brown’s self-assurance was reinforced by his membership in the Tuskegee Airmen, the elite all-black flying unit with whom Brown served stateside during World War II. Brown had trained as an officer, and as he rose through the ranks to captain he gained an appreciation for military meritocracy. Once, while Brown was traveling in the South as a second lieutenant, two white soldiers failed to salute him as he passed. Brown stopped them and took them aside. “You don’t salute me,” he told them, pointing to his shoulder. “You salute these gold bars. You don’t salute a man of any color; you salute his rank.” The soldiers saluted.

Not every incident ended as neatly. Brown endured the everyday outrages of racism and segregation, both as an officer and as a civilian. He was called names, was forced to ride at the back of the bus, and more than once was disrespected by a white officer. But the landmark legal blows to segregation in the postwar period encouraged Brown, and as the ’60s were dawning over the Kennedy White House, Brown held firm to his belief in the remedial powers of the Constitution and the courts. He was not about to cede, to separatists of any race, the hard-fought ground that had been gained.

“Dr. Brown is an extraordinary individual,” says Manning Marable, professor of public affairs, political science, history, and African-American studies at Columbia. “It’s very difficult for us to appreciate the challenges that faced Negro educators, administrators, and scholars at that time. There were no role models to speak of. Affirmative action didn’t exist. But Brown was there, though many of his colleagues would refuse to invite him to dinner, or have him in their church. He could barely live in their neighborhoods without being harassed.”

By 1961, a hundred years after the outbreak of the Civil War, social and economic conditions for the majority of blacks remained dismal. Throughout America, and particularly in the South, blacks were routinely brutalized by the police, terrorized by the Ku Klux Klan, and exposed daily to the dehumanizing realities of segregation. Many had lost hope of ever gaining equality under the American system; for them, Malcolm X’s appeal for a separate black nation within the United States had an irresistible seductiveness.

Brown took a different view. For him, integration was the true revolutionary idea, and he saw evidence that the train, though moving slowly, was on the right track. In 1948, the year Brown entered the Columbia School of Social Work, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, dismantling military segregation. Six years later, the Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education, rejected the “separate but equal” doctrine and ordered the desegregation of public schools. (Malcolm X often mocked the hollowness of that ruling, as schools in the South remained overwhelmingly segregated into the 1960s.) In 1955, the arrest of Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man, touched off the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a massive yearlong protest that culminated in the Supreme Court’s upholding a federal court decision that declared Alabama’s segregation laws for buses unconstitutional. And in 1956, Brown himself — the grandson of an ex-slave — became the first black professor in the history of Rutgers.

“There was an ideology among the Negro middle class of being a credit to your race, of racial uplift,” says Marable. “And to a large extent, Brown falls neatly into that category. He had great integrity, a commitment to excellence, and felt that he had to carry on his shoulders the aspirations of an entire race of people.”

William Neal Brown was born in Warrenton, Georgia, in 1919, the son of a poor black farmer and a Native American mother. When he was five, his family moved north to Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, where his father found work in the steel mill that would employ him for the next 47 years.

Brown’s mother had insisted that he attend integrated schools. At age 16, Brown graduated first in his high school class, but was barred from the National Honor Society because of his skin color. He had no money for college, and with the Depression at full tilt, he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, a relief program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. Brown worked on construction and forestry projects in Virginia, making $30 a month, most of which he sent home to his family.

One day, Brown was approached by an educational adviser at the camp who said he needed a typist in his office. Brown jumped at the chance. The adviser saw something in Brown and introduced him to the dean of men at nearby Hampton Institute. The dean got Brown enrolled in a work-study program. Brown worked on campus by day and took classes at night, and was able to pay his way through college.

Brown graduated in 1941, and like most Americans, he was dismayed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that December. He enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and arrived at Tuskegee in 1942. (Last March, Brown was among 350 Tuskegee Airmen and widows who collectively received the Congressional Medal of Honor at a ceremony in Washington.) A few months after the war ended, the mayor of Englewood, New Jersey, wrote to the Army requesting the services of a military man who could work with young boys who’d had scrapes with the law. Someone said to get Brown. Captain Brown got his discharge and headed north to Englewood. Two years later, through the GI Bill of Rights, he was able to buy a house and study social work at Columbia.

During his Columbia studies, Brown was assigned as a caseworker at the Veterans Administration in Newark. Within three years he himself became a supervisor of students, and it was in the course of meetings with other supervisors at Rutgers that Brown’s name came to the attention of Rutgers administrators. Brown was hired as an associate professor in the graduate school of social work and taught at Rutgers until retiring as professor emeritus in 1989.

Though intensely concerned with the problems facing black people in America, Brown was not an activist in the popular sense of the word. While others took part in sit-ins and Freedom Rides, Brown plied a quiet, unsung trade in the improvement of the mind: counseling emotionally troubled war veterans, lending his expertise in juvenile psychology to state agencies in New Jersey, and, in the lecture hall, fusing the work of Freud and Erikson in his course in human growth and development.

On the evening of November 3, 1961, Professor Brown drove from his home in Montclair, New Jersey, to the gymnasium of the Rutgers School of Pharmacy on Lincoln Avenue in Newark. Hundreds of people had packed the gym to hear the master rhetorician, Malcolm X.

When Brown arrived, he was met by a curious sight. Filing into the building two by two, in something like military cadence, was an endless regiment of young black men, all dressed in black suits, white shirts, and black bow ties. Brought to the event in six buses by the Nation of Islam, the “Fruit of Islam,” as the young men were called, had a vaguely perplexing effect on Brown as they filled up the last rows in the back of the gym.

“Whenever Malcolm X talked, they stood at attention,” Brown remembered. “When I talked, they sat down.”

What Brown didn’t know was that the Nation of Islam had a vital stake in this particular debate. The Chicago-based organization had established mosques in cities throughout the United States, including Malcolm X’s Mosque Number 7 on West 127th Street in Harlem, but it had yet to build one in New Jersey. The Nation hoped the debate would rally local support for that cause.

“The Negro community of Newark had a long history of being attracted to black nationalist sects,” says Marable, who is writing a biography of Malcolm X titled Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (Viking, 2009). “The best example is the Moorish Science Temple, founded in 1913 by Noble Drew Ali. Thousands of blacks in Newark were members, and still are to this day. Another thing that characterized Newark was rigid racial segregation — much more rigid than New York City — and the domination of a white ethnic elite over the black community. The Nation looked at Newark and said, ‘This is an ideal place.’”

With a reel-to-reel tape recorder rolling, Brown and Malcolm X put on a riveting polemical clinic that lasted over two hours. Brown, speaking extemporaneously with poise and eloquence, hung tough against Malcolm, whose mandarin politeness barely masked his contempt for the “Uncle Tom” Negro leadership that Brown was presumed to represent.

“Malcolm’s strategy from ’59 to around ’63 was to delegitimate the black middle-class leadership,” Marable says. “He was pushing for what you could call a black coalition or a united front — not from the leadership, but from the grass roots. His goal was twofold: to criticize the mainstream black leaders like James Farmer of CORE and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and also to reach out to average working-class blacks to say, ‘Follow us instead. We can voice your concerns far better than a Roy Wilkins or a Professor Brown.’”

Professor Brown, of course, was not so much a black leader as a stand-in for one, but that didn’t stop Malcolm from trying to pin on Brown’s tweedy lapels the emasculating label of “professional Negro.” At one point, Malcolm described the “modern Uncle Tom” as one who “speaks with a Harvard accent, an Oxford accent, and sometimes a Rutgers accent.” The line drew laughter and applause. Brown coolly dismissed Malcolm’s barbs as part of a “canned speech” that Malcolm had delivered in other cities and that served to distract from Brown’s points about the logistical impracticalities of creating a separate black state.

“I was a talented debater,” Brown said many years afterward. “I figured I could take Malcolm X.”

Whether he did or not is a matter of opinion.

“Brown’s perception is that he won the debate,” Marable says. “But if you had done a poll, I think that 90 percent of the people in the audience would have said that Malcolm won hands down.”

At the conclusion of the program, a PR person from Rutgers handed Brown the reel-to-reel tape of the event. Brown put the tape in his briefcase, and as he left the building he bumped into Malcolm X. “Malcolm said to me, ‘That was really nice. We should do it again in the Polo Grounds,’” Brown recalled with a laugh.

Six days later, Brown received a postcard from Phoenix. The card showed a beat-up wooden shack in the ghost town of White Hills, Arizona. On the back was a handwritten note: It’s better to live in a shack that you own, than in someone else’s mansion. It was signed Malcolm X.

The tape of the debate ended up packed away in Brown’s basement, and eventually forgotten. But three years ago, while going through some boxes, Brown uncovered the decades-old reel. He had never listened to it, and neither had anyone else. Thinking the material might be of historical interest, Brown contacted Columbia in hopes of bringing the document to light. (Please see pages 24 to 31 to read the first-ever published ex cerpts from the opening remarks of Brown and Malcolm X.)

The 1961 Brown–Malcolm X debate at Rutgers had a chillingly ironic postscript. As a result of the excitement generated by the event, the mosque that the Nation of Islam had envisioned in Newark was opened within a month. The mosque’s ultraconservative leadership, however, came to revile Malcolm X for his willingness, starting in the early 1960s, to work with the civil rights movement (culminating in his break from the Nation in 1964), and for his philosophical shift from racial separatism to a broader political humanism.

On February 21, 1965, three days after giving what would be his last public speech in the LeFrak Gymnasium at Barnard, Malcolm X was attacked inside the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights by several men who shot him repeatedly at close range. One man imprisoned for the murder, Talmadge Hayer, and two others whom Hayer implicated but were never arrested, had links to Temple Number 25 in Newark — the very mosque that the Brown-Malcolm X debate had helped to establish.

Neal Brown might not have won a popularity contest that night in Newark in 1961, but history will note that in the end it was Malcolm X who moved closer to Brown’s point of view, and not the other way around. Now, at 88, Brown is enjoying a sudden bestowal of laurels. Aside from being awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, Brown also received, in 2007, a Congressional Gold Medal from New Jersey senator Frank Lautenberg, as well as an Essex County executive proclamation citing Brown as “a courageous pioneer in breaking down racial barriers and promoting equality.”

Though slowed by age, Brown is still as confident and goaloriented as he was as a young man. He hopes to publish his papers in book form, as a living record of his career as an educator and social worker.

“I’ve had a beautiful life,” he said, “and I have a beautiful life coming up.”

He wasn’t talking about Heaven.

War of Words

William Neal Brown and Malcolm X squared off on November 3, 1961, in the packed gymnasium of the Rutgers School of Pharmacy. The following is an edited excerpt from their opening remarks.

William Neal Brown

Ladies and gentlemen. I shall try to defend the side of this question which says that there should be integration of the races in America rather than separation of the races in America. By separation I assume that we’re talking about a complete division of the white and black groups in this country. And I use white and black advisedly in deference to my friend Mr. X, who I know from his television appearances does not like the word Negro. I assume that by separation we’re talking about a complete division of white and black groups so that in effect they are two nations. By integration I assume that we mean the assimilation of all groups in the American nation on the basis of the person’s ability to produce and to contribute, without regard to race, color, or creed. On the basis of these definitions, I unhesitatingly take the position of integration.

I would like for you and Mr. X to know that I am well aware of certain injustices to the blacks in the current format of our country. I know well the history of the Negro in this country. I know how they were rounded up on the coasts of Africa and bundled into the holds of cargo boats. I know the inhumane conditions under which they were brought here and under which they worked, and that for some 300 years, this country has prospered off the sweat and labor of the black man. I know full well the economic struggles the Negro has had in this country. I know full well about our current struggle for educational and economic opportunity. These things I know as well as any of you. And I would be asinine to defend or rationalize them. I think my position is best described by Langston Hughes: I’m an American. You know what Langston Hughes says. He says, “I too sing America. I’m the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen when company comes. But I laugh and eat well and grow strong. Tomorrow I’ll sit at the table when company comes. Nobody will dare say to me eat in the kitchen then. Besides, they’ll see how beautiful I am and be ashamed. I too am America.” And that is how I speak tonight: as an American. Not as an African or an Ethiopian or an Arabian. I know nothing about those places except what I have learned from history books. But my forefathers and my father and I have lived in America, have shared in the growth of America, and will share in the future of America.

The first opposition I have to this matter of separation as it has been described is that it would simply reverse the current status quo, substituting bigotry for bigotry. We need only refer to the 1954 Supreme Court decision on segregation in the schools that says that separation is inherently unequal. As for myself and mine, I am not looking for an isolated place where I can simply be alone and withdraw. I am looking for equality.

My second point of objection to separation is that it makes black and white distinctions that are in reality impossible to make. As I look out at this audience I see not only black people and white people, I see all sorts of mixtures of colors, which is most representative of what America is as a nation. In the strictest biological sense I would wager that there are very few people in this room who are clearly white or clearly black. And if you trace your lineage, each of you, and I make no exception, you will find that we cannot draw black and white lines. I oppose the Black Muslim position because it draws hardand- fast black and white lines where no such lines can be drawn.

My third point is that separation is economically not a feasible proposition. In 1913 we had another religiously based movement headed by Noble Drew Ali, which was going to be the salvation of the black man. And it petered out for lack of a sound economic base. Some people in this room will remember the expedition to Africa by Marcus Garvey, who was going to take all the Negroes back to Africa and establish a black nation. And this too foundered for insufficiency of monetary capital and for lack of the business acumen to know what to do with the capital that they did have.

The only way to arrive at this economic ability is for the Negro to muscle and muster his way into the marketplaces of the country. To move in where real business is being done. To handle real money. And to learn how to handle money. And to handle money that pays American currency, not the currency of a separate black nation.

And now my last point. The Negro as a group has made tremendous strides against great odds in the last hundred years, probably greater than any group in the history of man over a comparable period of time. No group makes this kind of progress against overwhelming numerical and economic odds if everybody is against him. Nobody makes this kind of progress if there is not something in the social structure that makes this possible to be so. One of the great facts of U.S. history is that the Negro, no matter how ill-used, has remained deeply loyal to the United States, always hoping for the Year of Jubilo, sternly telling himself, “The very time I thought I was lost, the dungeon shook and the chains fell off.” You’ve got a right, I’ve got a right, we all got a right to the tree of life. The fruit is still rationed and often bitter. Negroes still are denied the right to the pursuit of happiness on equal terms with whites. Negroes still do the meanest jobs and get the lowest pay. They must slowly wrest from their white fellows a table at a restaurant, a desk in a school, a smile, the privilege of praying in a white church or using a white swimming pool.

Yet North and South, the Year of Jubilo seems a little closer. And with this I heartily agree. Fifty years ago I could not have stood at Rutgers University with classes of all white graduate students in front of me three days every week. I look with intense pride on the contributions of such Negro scientists as W. E. B. Du Bois, Carter Woodson, Franklin Frazier, and Dr. Charles S. Johnson. I look at the contributions in music of Marian Anderson and Duke Ellington. I look at Dr. Charles Drew, who discovered blood plasma, without which many a soldier would have lost his life in World War II. And I look on these with pride as contributions to an America of which I feel a part.

And this is the way I say it has to be done: that inch by inch we have to fight until we get an opportunity. And when the opportunity comes we have to show that we will be weighed in the balances and not found wanting. Mr. Malcolm X and I do not differ in the proposition that the Negro has been ill-used in America. We simply differ in the approach to the solution of this problem. And the approach that I see as most appropriate is to move in and demonstrate and become part of the warp and woof, the fabric of American life. I stand upon the position of integration.

Malcolm X

Mr. Moderator, Professor Brown, the student body, ladies and gentlemen. I must emphasize from the outset that I represent the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, who is not a politician. So I am not here as a Republican or a Democrat, not as a Mason or an Elk, not as a Christian or a Jew, not as a Catholic or a Protestant, not as a Baptist or a Methodist. Not even as an American. For if I was an American, the problem that confronts our people today would not exist. So I stand here and speak this evening as what I was when I was born — a black man.

Long before there was any such place as America, there were black people. And after America has long passed from the scene there will still be black people. I represent that which has no beginning or ending. That which is endless. That which is eternal. The black man himself.

I’m not here to make excuses for America’s weaknesses and shortcomings. I’m not here to defend America. Let America defend herself. I’m here to explain the weaknesses and shortcomings of the black man. In fact, I’m here to defend the black man.

I’m speaking as a black man first and foremost. Because speaking first and foremost as a black man is what gives me the right and the authority to speak for black people. What kind of black people does the Honorable Elijah Muhammad speak for? Black people who are jobless. The black masses who are poor, hungry, and angry. The black masses who are dissatisfied with the slums in which we have been forced to live. The black masses who are tired of the false promises of white politicians to correct the miserable living conditions that exist in our community. The black masses that are sick of the inhuman acts of bestial brutality practiced by semi-savage white policemen that patrol our community like an occupying army.

It is now time for the white man to listen to the black man. We have been listening to the white man long enough. We know him. We know how he thinks. We know what he thinks. And we know how he feels. The servant always knows the master. But the master never knows the servant. The greatest mistake the white man makes today is he thinks he knows how our people think and feel by listening to our so-called leaders. These Negro leaders have been handpicked and placed over our people by the white man himself. And these Negro so-called leaders always end up telling the white man exactly what he wants to hear. They actually mislead their own white benefactors, the so-called white liberals, by feeding them false information. The very same false propaganda that the liberal himself has manufactured. These Uncle Tom leaders have made you, the white man, think that you have plenty of time to get your house in order, plenty of time before your victim, the Negro, awakens and realizes what you have really done to him. But Mr. Muhammad is warning you that your time is already up. Your victim is more awake, more dissatisfied, more disillusioned, more impatient, and angrier than the Uncle Tom anemic leadership dares to tell you.

You are sleeping on a dangerous powder keg. A powder keg loaded with the explosive black feelings of 20 million ex-slaves. Twenty million second-class citizens. And if this powder keg that is already inside your house ever explodes it will blow you higher than the force of a billion 50-megaton bombs.

And as the eyes of these 20 million black people come open today, we can see that the white man’s American ship of state, a white ship of state, looks like it is sinking. And now that your white luxury liner seems to be on its way to the bottom, those of us who were forced by you to pay first-class fares even as second-class Negro passengers, are now being invited by you to come up on the top deck and mingle on a token integration basis with the white first-class passengers on what seems to be an already doomed ship. Do you think that our people at this late hour would be wise to accept your belated invitation, which is at best only an invitation to share your doom?

The anemic Negro leadership that is willing to settle for token integration instead of complete separation is only asking for continued slavery. And these Uncle Tom Negroes do not represent the true sentiments or feelings of the masses of our oppressed people.

This modern Uncle Tom is dangerous to the black masses because as long as the white man can pacify Uncle Tom with a few crumbs like token integration, the plight of the black masses remains unresolved.

Only a few handpicked Negroes benefit from token integration. Usually these handpicked Negroes are the type who take pride in being among the chosen few who are allowed to be around the white man. And usually this integration-happy Negro is so white-minded he’s more anti-black than the white man himself is. He sees the narrow door opened by token integration as a chance for him to escape from being around too many of his own people, while the masses must remain in the Negro slums.

Many of you misunderstand us and think we are advocating continued segregation. No. We reject segregation even more militantly than you do. We want separation but not segregation. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us that segregation is when your life and your liberty is controlled or regulated by someone else. But separation is that which is done voluntarily by two equals. As long as our people here in America are dependent upon the white man, we will always be begging him for jobs, food, clothing, and housing. And he will always control our lives, regulate our lives, and have the power to segregate us.

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad says that for four hundred years our people have been living like children in the white man’s house. We have looked to the great white father of this house to supply us with our every need. With our jobs. With our food. With our clothing. With our shelter. Even with our schools. Yet we have nerve enough to resent it when the white man treats us like children by segregating us. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad says that if we think we have now become equal to the great white father who has been caring for us up till now, then we should prove it by separating from the white man.

And since no sane white man really wants integration, and no sane black man really believes we will ever get anything more than token integration, the only immediate solution is complete separation. Therefore, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad is demanding that several states be set aside for the twenty million ex-slaves, and with the help of Allah he will show our people how to solve our own problems. We won’t be forcing ourselves into white communities, into white schools, and into white factories. We will set up and run our own. I thank you.