How Zora Neale Hurston’s Love for a Fellow Columbia Student Changed American Literature

In the spring of 1936, Zora Neale Hurston ’28BC — novelist, short-story writer, essayist, ethnographer, choreographer, playwright, and key figure of the Harlem Renaissance — left her apartment at 116th Street and Seventh Avenue and sailed to Jamaica. On the surface, this voyage was a professional triumph: she’d spent years trying to get grant money to study the spiritual practices of African diaspora communities in the West Indies, and now the Guggenheim Foundation had offered her a fellowship to research Obeah, a belief system found throughout the Caribbean.

Yet as the steamship plowed the waters, Hurston felt bluer than the sea itself. At forty-five, she was escaping what she would later call “the real love affair of my life” — the sort of euphoric, desperate, impossible love that a heart can bear but once. “I did not just fall in love,” she writes in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road. “I made a parachute jump.”

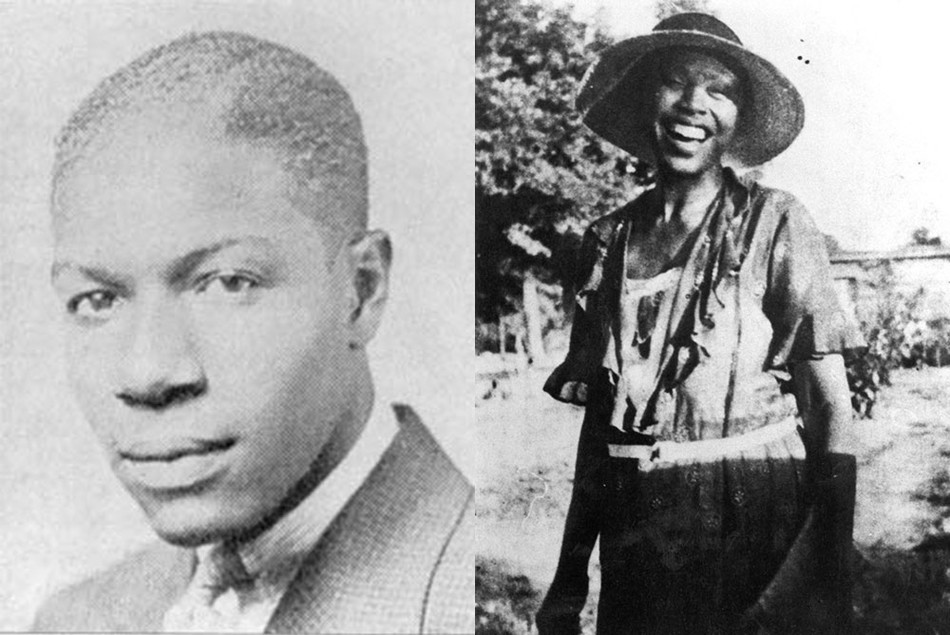

The man who precipitated this leap was Percival “Percy” Punter ’35GSAS. In 1931, when Hurston was forty, she enlisted Punter, a nineteen-year-old student at City College, to perform in her revue The Great Day, set in a Florida railroad camp. Billed as “A Program of Original Negro Folklore, with a Choral and Dramatic Cast,” the show was based on material that Hurston had gathered during an ethnographic study of Black life in Florida and Alabama, which she had begun while a student at Barnard under Columbia professor Franz Boas, known as the father of American anthropology. With the show, Hurston, for whom the aesthetics of Black folkways were of the highest order, wanted to present the “unbelievable originality” of this expression in its pure, unselfconscious form, free from formal training or commerce. With funding from her patron, Charlotte Osgood Mason, a domineering Park Avenue socialite obsessed with the mystical vitality of “primitive” American art untouched by the white culture industry, Hurston brought The Great Day to Broadway’s John Golden Theatre for a single performance in January 1932.

Punter played the role of the shack-rouser, whose job was to awaken the camp at dawn. In her book, Hurston describes Punter as “tall, dark brown, magnificently built” with “a bright soul, a fine mind in a fine body, and courage.” His parents, McGuire and Unettia Punter, were immigrants from the small Caribbean island of Barbuda, and Punter grew up in San Juan Hill, a culturally vibrant Black and Puerto Rican tenement district in Manhattan that would later be razed to build Lincoln Center.

Hurston, who had divorced her husband, Herbert Sheen, in the summer of 1931, was enamored of Punter, though no one knew it. “I made up my mind to keep my feelings to myself,” Hurston writes, “since they did not seem to matter to anyone else but me.”

What she didn’t know was that Punter had feelings for her. In their mutual reticence — which was really a mutual caution — they each perceived in the other a lack of interest, and so were left to tend their flames in an aching privacy. Soon they drifted apart. Hurston went back south and wrote her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, then won a Rosenwald Fund fellowship to pursue a PhD in anthropology at Columbia under her mentor Boas.

Hurston began her graduate studies in early 1935, but her fellowship was reduced, ostensibly over a dispute with Rosenwald president Edwin Embree over her academic plan. (Later, in a letter to anthropologist Melville Herskovits 1923GSAS, Hurston conjectured that some harsh words that she leveled at the white president of Fisk University, Thomas Jones ’26GSAS, had reached Embree and turned him against her.) Low on funds in the midst of the Great Depression, Hurston dropped out of the doctoral program after a semester. Punter, meanwhile, had entered graduate school at Columbia in 1934, and when the two met again, Hurston was struck afresh by the young man’s intellect, character, and attractiveness. “He had all of those things and more,” she writes. “It seems to me that God must have put in extra time making him up. He stood on his own feet so firmly that he reared back.”

Punter began making “shy overtures” to Hurston, who “pretended not to notice for a while so that I could be sure and not be hurt.” Then he came out with it: he’d been in love with her all along. One day, Hurston recounts, he said, “You know, Zora, you’ve got a real man on your hands. You’ve got somebody to do for you. I’m tired of seeing you work so hard. I wouldn't want my wife to do anything but look after me.” The reference to marriage electrified Hurston. “With those words he endowed me with Radio City, the General Motors Corporation, the United States, Europe, Asia and some outlying continents. I had everything!”

If Hurston had everything, Punter perhaps had a little more than he’d bargained for.

Surely he had never met a woman as talented, bold, and exciting as Zora. She had grown up in Eatonville, Florida, one of the first all-Black incorporated towns in the United States (her father, John Cornelius Hurston, was mayor), and her worldview was shaped by the norms conferred by Black self-governance: citizenship, equality, and individuality. Her high self-regard was joined by a humming intellect, a barbed Algonquin-worthy wit, a lavish gift for storytelling, and a keen eye and ear for the human note, which would serve both her literary and ethnographic work. She was so impressive that the founder of Barnard College, Annie Nathan Meyer, having met Hurston at a dinner in 1925, personally arranged her admission; and Hurston, an English major, became Barnard’s first Black graduate.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Hurston’s short stories and essays had lit up the literary skies, and by the time she reunited with Punter she was a full-blown celebrity. She was also a lively, funny, fascinating raconteur with a busy social calendar — which spelled danger to Punter. He was quick to jealousy and turned dour in the company of Hurston’s literary friends. “I would interpret his moods as indifference and die, and die, and die,” Hurston recalls in her memoir. “The terrible thing was that we could neither leave each other alone, nor compromise. Let me seem too cordial with any male and something was going to happen. Just let him smile too broad at any woman, and no sooner did we get inside my door than the war was on!” Hurston is frank about her own gnawing jealousy: “He was so extraordinary that I lived in terrible fear lest women camp on his doorstep in droves and take him away from me.”

Punter wanted Hurston to marry him and give up her career. He seemed to take her devotion to her work as an attack on his love. “He felt that he did not matter to me enough,” Hurston states. “He was the master kind. All, or nothing, for him.” Hurston, of course, could never give up writing — but how could she give up love? Together, she and Punter were “alternately the happiest people in the world, and the most miserable,” caught in a “fiendish trap” so agonizing that “our bitterest enemies could not have contrived more exquisite torture for us.”

And so when Hurston, in the spring of 1936, set sail for the Caribbean, she wasn’t just advancing her career — she was trying to save her life: “This was my chance to release him, and fight myself free from my obsession.”

The pain of separation was unbearable. Hurston worked in Jamaica from April to September, living among the Maroons, people descended from those who had escaped slavery in Jamaica and settled in the island’s Blue Mountains. “I pitched in to work hard on my research to smother my feelings,” Hurston writes. Still, she longed for Punter. “Everywhere I set my feet down, there were tracks of blood. Blood from the very middle of my heart.”

After Hurston’s five months with the Maroons, her fellowship was extended, allowing her to sail on to Haiti to study the practice and culture of voodoo. It was during this sojourn, in a seven-week burst, that she wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God.

A lyrical novel set in a fictionalized Eatonville and rendered in the Black dialect of Central Florida, the book centers on Janie Crawford, whose innocent notions of love meet the realities of two passionless, repressive marriages — the first, at seventeen, to a reputable landowner, the second to Jody Starks, the prosperous, puffed-up founder of the all-Black town. Soon after Starks’s death, Janie, forty and childless, flouts convention by starting a love affair with a carefree drifter called Tea Cake, who is fifteen years her junior. The townsfolk are scandalized, and some fear that the penniless young man is after Janie’s money. But as one member of the Greek chorus of porch-sitters outside the general store says, “Still and all, she’s her own woman.”

Janie falls hard for Tea Cake. Their love is real. But Tea Cake’s pride, his earnest desire to serve Janie, together with his insecurity add bitter fuel to their passion. It’s not hard to interpret the climax of the novel as Hurston’s symbolic resolution of her love for Punter. As she writes in Dust Tracks on a Road, “The plot was far from the circumstances, but I tried to embalm all the tenderness of my passion for him in Their Eyes were Watching God.”

The novel, published in 1937, was polarizing. Everyone acknowledged Hurston’s gifts, but for the politicized male intellectuals of the New Negro movement, her novel was a step backward, a betrayal of their notion of literature as a tool for social change. Richard Wright, who at the time was Harlem bureau chief of the Communist Party’s newspaper the Daily Worker, assailed the novel’s “facile sensuality” and accused Hurston of employing the tropes of minstrelsy for the benefit of white readers. This view was shared to varying degrees by Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, and Ralph Ellison. She had faced similar criticisms of insufficient militancy for Jonah’s Gourd Vine: “Many Negroes criticize my book because I did not make it a lecture on the race problem,” she told an interviewer. “I was writing a novel, not a treatise on sociology. There is where many Negro novelists make their mistake: they confuse art with sociology.”

After nearly two years in the Caribbean, Hurston returned to New York. Punter was still on her mind, and when she learned that he had left his number with her publisher, she froze. She had no idea what he would say if they spoke, or how she would feel, and months passed before she dared pick up the phone. When she did, they agreed to meet, and Hurston was happy to find the same “shy, warm man I had left.” In Dust Tracks on a Road she reports that they talked and discovered that they had both spent so much time needlessly tormenting themselves with phantom suspicions. “I found out that he was a sucker for me,” Hurston writes, “and he found out that I was in his bag.” It pleased Hurston that in her absence Punter had neither fallen apart nor shot to stardom in his profession. Rather he had “settled down to a plodding desk job” with the New York State Employment Service. “He had let his waistline go a bit and that bespoke his inside feeling. That made me happy no end. No woman wants a man all finished and perfect. You have to have something to work on and prod.”

Hurston ends her discussion of Punter with cryptic speculation about their future (the book, published in 1942, leaves things in 1938): “What will be the end? That is not for me to know . . . What I do know, I have no intention of putting but so much in the public ears.” She goes on to say that when she was a little girl and read the Greek parable of the choice of Hercules, “I was so impressed that I swore an oath to leave all pleasure and take the hard road of labor. Perhaps God heard me and wrote down my words in His book. I have thought so at times. Be that as it may, I have the satisfaction of knowing that I have loved and been loved by the perfect man. If I never hear of love again, I have known the real thing.”

The promise Hurston had felt upon her reunion with Punter never did blossom like the pear tree in her novel, a symbol of Janie’s hopes and desires. By 1939, both Hurston and Punter were married to other people. Hurston, forty-eight, married Albert Price III of Jacksonville, a twenty-three-year-old college student. (Hurston, who was known to alter her age when it suited her, declared on the marriage license that she was born in 1910, which would have made her twenty-nine). They were divorced in 1943. Punter and his wife, Marian, settled in Elmhurst, Queens, where they raised a daughter. He took a job with the US Labor Department and rose to the position of regional administrator of the Bureau of Employment Security for Region II, which covered New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. He died in 1985.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Hurston struggled to work and publish. Wright and Ellison, whose fiction offered trenchant critiques of American racism, were ascendant. Hurston’s complicated, often alienating political and social views, together with the changing tastes of the reading public, hastened her decline. She spent her last years in Florida in the St. Lucie County Welfare Home, her books out of print and her name all but forgotten. Ailing and destitute, Hurston died in 1960 from heart disease at age sixty-nine and was buried in an unmarked grave.

In 1973, the writer Alice Walker, having read about Hurston’s fate in an anthology on the Harlem Renaissance, set out to purchase a headstone for Hurston. She had it engraved with the words “Zora Neale Hurston: A Genius of the South.” Walker wrote an essay about her journey called “Looking for Zora,” which was published in 1975 in Ms. The piece resurrected Hurston as a brilliant and brave writer who affirmed with Their Eyes Were Watching God that the inner life and choices of a young Black woman in a small Southern town was the stuff of literature. By the end of the decade, Hurston was being celebrated as the literary mother of a new generation of Black women writers.

In bringing her skills as an ethnographer to bear on her fiction, and with an unfailing ear for speech and expression, Hurston was now credited with dignifying an authentic folk culture that Black urban writers of the 1930s and ’40s had repudiated. As Farah Jasmine Griffin, a professor of African-American and African-diaspora studies at Columbia, has said, “Hurston elevates Black language to a level of poetry. She shows the worldview that one gets from language, which is a very spiritual one.”

It is perhaps ironic that Hurston’s love for a man inspired a work of art whose central theme is female independence. But then again not: for her affair with Punter was her prerogative — she chose it freely, and she accepted its hard and beautiful lessons. As an older, wiser Janie says to her friend Pheoby at the novel’s end: “Two things everybody’s got tuh do fuh theyselves. They got tuh go tuh God, and they got tuh find out about livin’ fuh theyselves.”

This article was originally published on February 3, 2022. It was last updated on March 23, 2022.