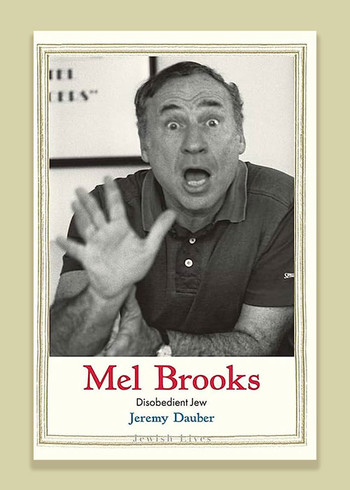

In Mel Brooks: Disobedient Jew, Jeremy Dauber, the Atran Professor of Yiddish Language, Literature and Culture at Columbia, describes the filmmaker and comedian's provocative, inexhaustible, and enduring impact on American culture.

Your book is part of the Jewish Lives biography series, which spotlights a pantheon of greats — Einstein, Anne Frank, Wittgenstein. Why include the man who gave us Blazing Saddles?

The short answer is “because they asked.” But really because Brooks did so much to shape not just Jewish comedy and American comedy, but also how American Jews thought about themselves in the second part of the twentieth century. With all the documentaries and books we’ve seen, that story is still under told.

Tell us more about that narrative.

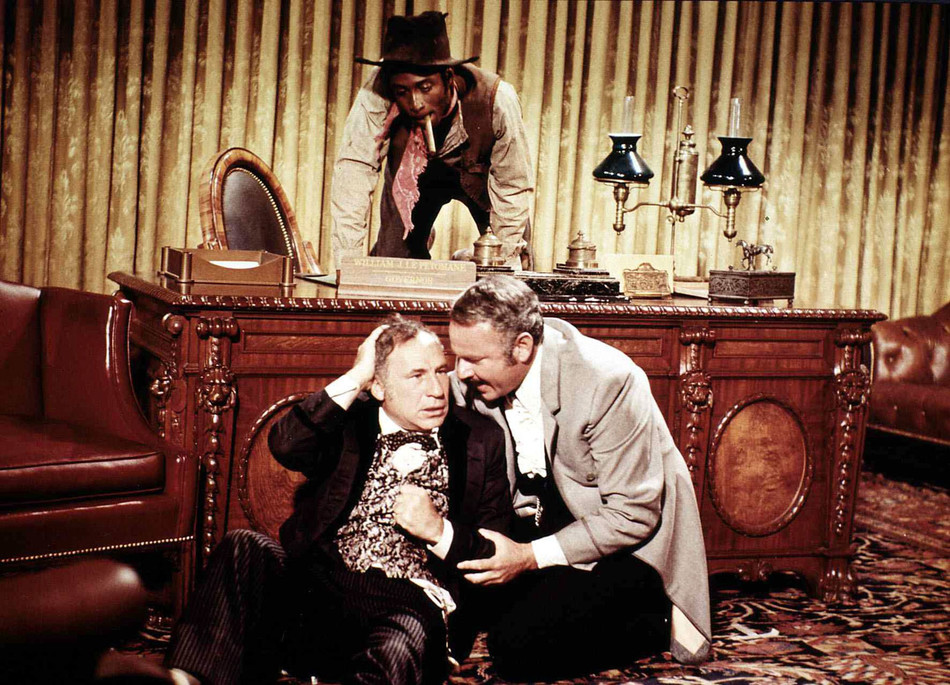

It’s about the Jewish embrace of America and America’s embrace of the Jews in the postwar period. It’s about Jews wanting to be welcomed into America as full citizens, but also remaining a kind of loyal opposition. It’s about subscribing enthusiastically to American values, but also saying “we’re still enough outside the American dream to show the holes and parody it.” We see that duality when Brooks lampoons Westerns and monster movies, the very genres that enchanted him as a child.

It’s also about the desire to be at the heart of the cultural story. So, you see Brooks going from the Jewish enclave of the Catskills to television and Broadway and to box office success as a director and leading man who is not hiding his Jewishness. He did change his name from Melvin Kaminsky to Mel Brooks, but his inflection is Yiddish, he uses Yiddish words, and he is unabashedly, unashamedly, disobediently, himself — even if that self, like so many Jewish selves back then, was born under a different name.

Jewish Americans are no longer kept out of the clubs, professions, neighborhoods, and larger culture in ways seen even a generation ago. You have taught a course on comedy for the past twenty years. Do today’s students need help seeing how much has changed?

Absolutely. But we also discuss how history is not necessarily a straight line. It would be wonderful if we could say society is always moving toward less discrimination, but that’s not the case. So, it’s useful to view Brooks’ movies as moments in which these vectors move back and forth.

Do students still find Brooks funny?

Good question! Comedy can get stale. I teach Aristophanes in the Core Curriculum, and sometimes we have to say, “I’m sure this was hilarious back in Athens.”

Still, with Brooks, subjects you would think belong to the past have become newly relevant, sometimes tragically so. In 2004 when I taught The Producers, with the famous “Springtime for Hitler” musical number, there was almost a quaintness in discussing that film’s pungency about Nazis. Students would understand that a Nazi chorus line and Nazi jokes were probably something that bothered people in 1968, but twenty years ago we were not really thinking about Nazism as a contemporary threat. Today, unfortunately, we are grappling with Nazism again.

In the book you show how intensely Brooks hated Nazis, and how he used humor as a weapon.

He served in WWII. He fought in Europe. His brother was shot down and was a prisoner of war. So he comes by the rage quite honestly. While Brooks would have been the first to say that humor would not have been sufficient to defeat Nazism, he definitely saw his comedy as a continuation of the fight against Nazism by other means.

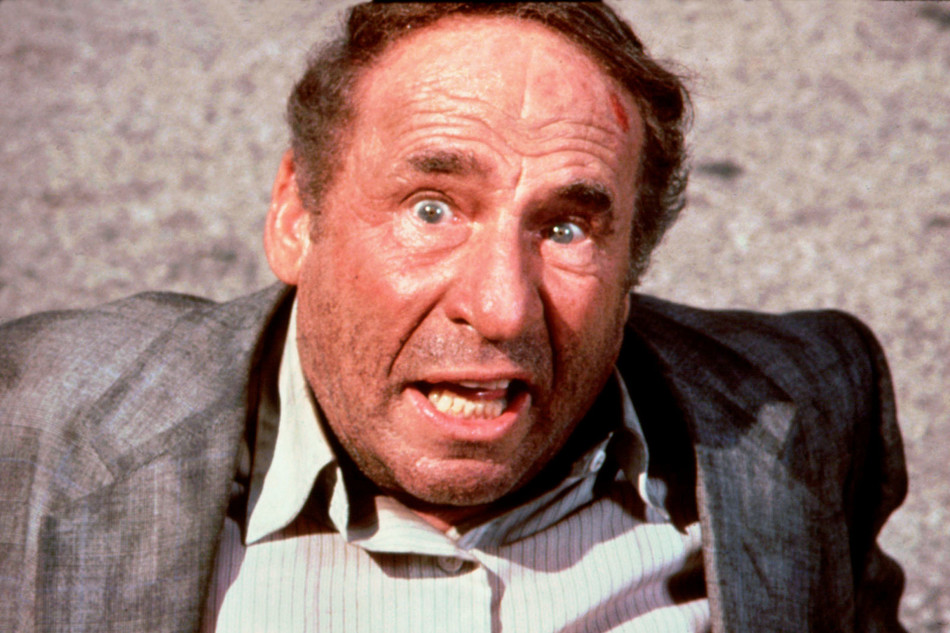

More broadly, Brooks says about Blazing Saddles, “we’re going to take on every cliché in the book and hope that we’re going to kill them off in the process.” And he does, but still with a laugh line. Brooks makes his points about stereotypes in Westerns and in current society. But he’s not making the audience feel attacked — he always wants you to laugh with him. There’s a little song he sang early in his career that ends, “and please love Melvin Brooks.” That gets to the heart of the tension, the ping-ponging between rebellion and allegiance, the disobedient aggressiveness in the comedy and the desire to be loved,

He was everywhere over the decades — from the Borscht Belt to Broadway to TV to the “2000 Year Old Man” LPs to the movies. He worked with everyone from Eddie Cantor to Dave Chapelle to Wanda Sykes. This year, at age 96, he came out with History of the World Part II. What accounts for his longevity and ubiquity?

Brooks is a brilliant improvisationalist. He is able to see what’s out there in the culture, run it through his own brilliant comic sensibility, and offer up something new. He also happened to be at the center of arguably the first big comedy show on television, Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows. So, he was able to meet and connect with everyone and keep those connections going.

His first film The Producers, came out in 1967. His second, The Twelve Chairs, was drawn from a Russian satire of the 1920s. While not a huge success, it does show a more highbrow side, one encouraged by his Russian born comedy-writing mentor, Mel Tolkin. You relate that Brooks named his son after Nikolai Gogol, and as a producer took on serious films like The Elephant Man. Isn’t that intellectual bent a little surprising from an auteur made famous by flatulence?

In writing a biography you want to take people where they are at any given point in their lives and think about the decisions they are making. When Brooks came off The Producers, he didn’t know he was going to become hugely successful by making Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein. He was thinking, “I got an Oscar for writing the screenplay, but The Producers didn’t make a huge box office sale — what am I gonna do now?”

And there were clearly detours along the way.

Take all of his failures in Broadway theatre in the 1950s and ‘60s. If one of them had become a huge hit, we might think of Mel Brooks the Broadway impresario. And if The Twelve Chairs had been a real success, maybe we would have seen a very different Mel Brook as a director.

You relate how Barack Obama once told Brooks that watching Blazing Saddles as a child gave him hope because it showed that there could be a Black sheriff. That film does seem to have reached everyone.

Absolutely. When it comes to the American movie-going public, Brooks was monumentally influential.